Despite Misleading Reporting, Guaranteed Income Programs Help Families

By Ashley Burnside

Guaranteed income programs are a critical tool for providing people with enough cash to not only meet their basic needs, but to thrive. In recent years, guaranteed income pilots have launched throughout the nation, providing different amounts of unrestricted cash transfers for varying durations to targeted populations. [1] Results have overwhelmingly demonstrated the success of these payments in helping recipients achieve economic well-being. [2] Programs like the Magnolia Mother’s Trust and Rx Kids have revolutionized how policy experts think about cash transfers as tools for promoting positive health outcomes and economic prosperity.

But despite these positive examples of guaranteed income, recent reporting in The New York Times [3] about the Baby’s First Years study [4] has questioned the success of such programs. There are many reasons to be wary of such a broad conclusion, including confounding factors within the study and the fact that the research is still ongoing. This study represents just one of many and should not be used as a reason to ignore the years of comprehensive research and participant testimonials demonstrating the positive outcomes of guaranteed income.

What are the Details of the Baby’s First Years Study?

The Baby’s First Years study aimed to assess how poverty reduction through cash transfers to families with babies impacts cognitive and brain development, among other variables. One thousand families with incomes below the federal poverty line across four regions were included in the study to either receive $333 per month or $20 per month from the child’s birth through the child’s sixth birthday. The study was conducted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, with recruitment ending in June 2019. Study participants engaged in various research tests and metrics to assess the child’s development at different stages of life.

This past summer, study researchers released a new working paper summarizing their findings on how participating babies’ brain development changed during the first four years of the study. Some of the metrics measured included language skill development, prevalence of behavioral problems, executive functioning, and cognitive development, measured through high-frequency brain activity. The researchers found no statistically significant differences between the treatment and control groups across these metrics.

Researchers also interviewed participating caregivers and found that the higher payments provided many moments of joy and special treats for caregivers and their children, such as being able to buy their child a new winter coat.

Research Limitations and Other Factors Must Be Considered

The New York Times reporting labeled the study findings as undercutting the idea of cash payment helping child development. However, there are many factors that contribute to these findings. First, the monthly payments provided in this study of $333 per month simply may not be enough to make a measurable difference in the families’ economic conditions. These payments were not adjusted based on the size of the family, meaning if one family had three children, their $333 monthly payment would be stretched further than for a family with just one baby. The payments also were not adjusted for inflation during the six years of the study, when families faced increased costs of living. As a result, nearly all parents in both payment groups remained low-income during the four years of the study–the payments were not high enough to lift families out of financial hardship.[5]

Second, the unfortunate timing of the study cannot be overlooked. The COVID-19 pandemic upended the economic stability of families throughout the nation as employment became precarious, child care centers closed, and families became isolated. This likely increased the stress families faced and created a financial burden. During the pandemic, the federal government also provided emergency cash to help families stay afloat. Eligible families received three stimulus payments totaling $3,200 per adult and $2,500 per child, an expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC) of $3,600 per child for children under the age of six, expanded unemployment insurance payments, and more. These temporary increases in income, which went to both the treatment and control groups in this study, could have impacted the measured results across both groups of families.

Third, this study only measures very particular outcomes: childhood development. Studying brain development through medical testing of children experiencing poverty is tokenizing, and solely measuring such changes to determine the success of the treatment is flawed. Medical testing of the brain functioning of marginalized communities has a complex history rooted in racist and classist assumptions about intelligence and biology. No matter what the intention or research question, this history and the implications of it, and the emotions that may come with undergoing such medical evaluation, must be considered. Even if researchers found no measurable changes in brain functioning based on these specific developmental metrics, providing cash to families still has great value. The researchers found that parents who received higher monthly payments were able to spend more time with their children, such as reading to them more. [6] Research has found that caretakers reading more to their children is correlated with child vocabulary and literacy skill development. [7] Some of the outcomes being measured in this study also may show up later in life, such as when the children are in school.

Fourth, we must center and validate research beyond quantitative metrics. Qualitative findings that come from interviews with caregivers and focus groups are equally important for understanding the impact of programs like cash transfers. For example, a caregiver being able to tell her child yes to more things, or buying a birthday cake for her child, are important experiences for having a happy and fulfilling childhood. They are opportunities that can make caregivers feel more empowered and joyful. These kinds of outcomes can best be measured through interviews and should not be overlooked. After all, one of the lead researchers in the Baby’s First Years study who led parent interviews said, “The mothers are certainly not saying this money doesn’t matter.” [8] Media reporting should center these impacts too, not just the quantitative findings.

Multiple Programs Have Measured the Benefits of Cash Transfers for Families

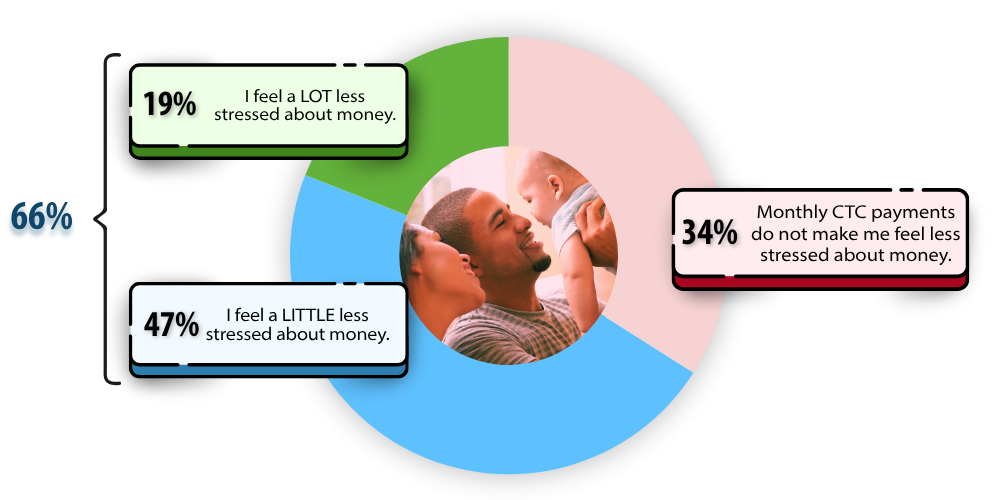

Numerous other research studies have found positive effects from cash transfers for families. CLASP, in collaboration with other partner organizations, conducted a three-part survey of over 1,000 families to assess the impact of receiving the expanded CTC payments in 2021. [9] Our surveys found that the monthly payments helped parents afford essentials—bills, groceries, and rent/mortgage payments. Nearly 70 percent of families who received the monthly payments said they reduced their financial stress [10] (Figure 1). And about one-quarter of the parents who got the monthly payments said they made it easier for them to work, or work more hours. [11] Part of the reason for this is that it costs money to maintain employment, and if a worker is one emergency away from a financial spiral, that puts them at high risk for forced unemployment. For example, if a car breaks down, the worker doesn’t have the savings to fix it, and they live in a community without reliable public transportation, how would they get to their job? One parent interviewed for the CTC survey project explained that the CTC monthly payment is what allowed them to get their car repaired.

Figure 1. A Majority of Monthly CTC Recipients Report Reduced Financial Stress as a Result of the Program:

When asked, “Which statement best matches how you feel about the monthly CTC payments?” measured in percentage of respondents who receive monthly payments

The Rx Kids program in Flint, Michigan has produced compelling findings of how universal payments for pregnant people and newborn babies can positively benefit the well-being of both generations. [12] Rx Kids provides a one-time payment of $1,500 during pregnancy and monthly payments of $500 during the first year of life. [13] All families with newborns in Flint are eligible for the payments so long as they can prove their city residency. This program has been in place since 2024 and positive outcomes have already been reported. In addition, the program has expanded to eleven pilot sites throughout the state of Michigan, including Kalamazoo, Pontiac, and certain counties in the Upper Peninsula.

When comparing the health outcomes of parents in Flint before the program began and in comparable cities, families receiving Rx Kids had positive birth weight outcomes, and reductions in premature births and neonatal intensive care unit admissions. [14] Mothers enrolled in Rx Kids also reported better maternal mental health outcomes: being less likely to suffer from postpartum depression and anxiety and more likely to report feeling loved and valued. [15]

Magnolia Mother’s Trust provides cash support for Black mothers with low incomes in Jackson, Mississippi. [16] In addition to a monthly, unrestricted cash payment of $1,000 for twelve months, the program also provides social and emotional support for participants and various supportive services. The program has a two-generation approach, also offering a 529 Children’s Savings Account for the children of participating moms. Among many positive financial and emotional well-being changes reported for the 2022-2023 cohort, the percent of moms who were employed increased after receiving the payments at a statistically significant level. [17] This is an example of one of many studies that have refuted the tired cliché of cash transfer programs disincentivizing work among participants.

These are just two of the many innovative cash transfer programs being implemented throughout the nation that are having positive outcomes for children and caregivers.

Guaranteed Income Benefits All

Everyone deserves enough cash to make ends meet. We are all better off when caregivers can afford baby formula and have time to read to their children because they don’t need to take on extra gig work to afford rent. When we choose to invest in caregivers and in babies, that promotes long-term, positive outcomes. [18] Existing public benefit programs are critical but can leave out families who are struggling because of work requirements, [19] time limits, [20] behavioral requirements, [21] and stigma. [22] Targeted cash transfers are a critical tool that policymakers must consider implementing to ensure investments in all children.

Research from the COVID-19 pandemic and from guaranteed income pilots throughout the nation, and around the globe, provides overwhelming evidence that this model works. Simply providing cash to people improves well-being, decreases parental stress, and reduces poverty. The media sensationalism of one study should not mute those critical findings. Guaranteed income works.