CLASP

The Center for Law and Social Policy

By Suzanne Wikle

The effect of H.R. 1 on the 10 non-expansion states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) did not receive the same attention as the bill’s primary Medicaid provisions. But Medicaid programs in these states will also be harmed by the bill. Eligibility and financing changes will force non-expansion states to make difficult decisions and likely lead to reduced services, lower provider reimbursement rates, and hospital closures.

By Ashley Burnside

Guaranteed income programs are a critical tool for providing people with enough cash to not only meet their basic needs, but to thrive. In recent years, guaranteed income pilots have launched throughout the nation, providing different amounts of unrestricted cash transfers for varying durations to targeted populations. [1] Results have overwhelmingly demonstrated the success of these payments in helping recipients achieve economic well-being. [2] Programs like the Magnolia Mother’s Trust and Rx Kids have revolutionized how policy experts think about cash transfers as tools for promoting positive health outcomes and economic prosperity.

But despite these positive examples of guaranteed income, recent reporting in The New York Times [3] about the Baby’s First Years study [4] has questioned the success of such programs. There are many reasons to be wary of such a broad conclusion, including confounding factors within the study and the fact that the research is still ongoing. This study represents just one of many and should not be used as a reason to ignore the years of comprehensive research and participant testimonials demonstrating the positive outcomes of guaranteed income.

What are the Details of the Baby’s First Years Study?

The Baby’s First Years study aimed to assess how poverty reduction through cash transfers to families with babies impacts cognitive and brain development, among other variables. One thousand families with incomes below the federal poverty line across four regions were included in the study to either receive $333 per month or $20 per month from the child’s birth through the child’s sixth birthday. The study was conducted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, with recruitment ending in June 2019. Study participants engaged in various research tests and metrics to assess the child’s development at different stages of life.

This past summer, study researchers released a new working paper summarizing their findings on how participating babies’ brain development changed during the first four years of the study. Some of the metrics measured included language skill development, prevalence of behavioral problems, executive functioning, and cognitive development, measured through high-frequency brain activity. The researchers found no statistically significant differences between the treatment and control groups across these metrics.

Researchers also interviewed participating caregivers and found that the higher payments provided many moments of joy and special treats for caregivers and their children, such as being able to buy their child a new winter coat.

Research Limitations and Other Factors Must Be Considered

The New York Times reporting labeled the study findings as undercutting the idea of cash payment helping child development. However, there are many factors that contribute to these findings. First, the monthly payments provided in this study of $333 per month simply may not be enough to make a measurable difference in the families’ economic conditions. These payments were not adjusted based on the size of the family, meaning if one family had three children, their $333 monthly payment would be stretched further than for a family with just one baby. The payments also were not adjusted for inflation during the six years of the study, when families faced increased costs of living. As a result, nearly all parents in both payment groups remained low-income during the four years of the study–the payments were not high enough to lift families out of financial hardship.[5]

Second, the unfortunate timing of the study cannot be overlooked. The COVID-19 pandemic upended the economic stability of families throughout the nation as employment became precarious, child care centers closed, and families became isolated. This likely increased the stress families faced and created a financial burden. During the pandemic, the federal government also provided emergency cash to help families stay afloat. Eligible families received three stimulus payments totaling $3,200 per adult and $2,500 per child, an expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC) of $3,600 per child for children under the age of six, expanded unemployment insurance payments, and more. These temporary increases in income, which went to both the treatment and control groups in this study, could have impacted the measured results across both groups of families.

Third, this study only measures very particular outcomes: childhood development. Studying brain development through medical testing of children experiencing poverty is tokenizing, and solely measuring such changes to determine the success of the treatment is flawed. Medical testing of the brain functioning of marginalized communities has a complex history rooted in racist and classist assumptions about intelligence and biology. No matter what the intention or research question, this history and the implications of it, and the emotions that may come with undergoing such medical evaluation, must be considered. Even if researchers found no measurable changes in brain functioning based on these specific developmental metrics, providing cash to families still has great value. The researchers found that parents who received higher monthly payments were able to spend more time with their children, such as reading to them more. [6] Research has found that caretakers reading more to their children is correlated with child vocabulary and literacy skill development. [7] Some of the outcomes being measured in this study also may show up later in life, such as when the children are in school.

Fourth, we must center and validate research beyond quantitative metrics. Qualitative findings that come from interviews with caregivers and focus groups are equally important for understanding the impact of programs like cash transfers. For example, a caregiver being able to tell her child yes to more things, or buying a birthday cake for her child, are important experiences for having a happy and fulfilling childhood. They are opportunities that can make caregivers feel more empowered and joyful. These kinds of outcomes can best be measured through interviews and should not be overlooked. After all, one of the lead researchers in the Baby’s First Years study who led parent interviews said, “The mothers are certainly not saying this money doesn’t matter.” [8] Media reporting should center these impacts too, not just the quantitative findings.

Multiple Programs Have Measured the Benefits of Cash Transfers for Families

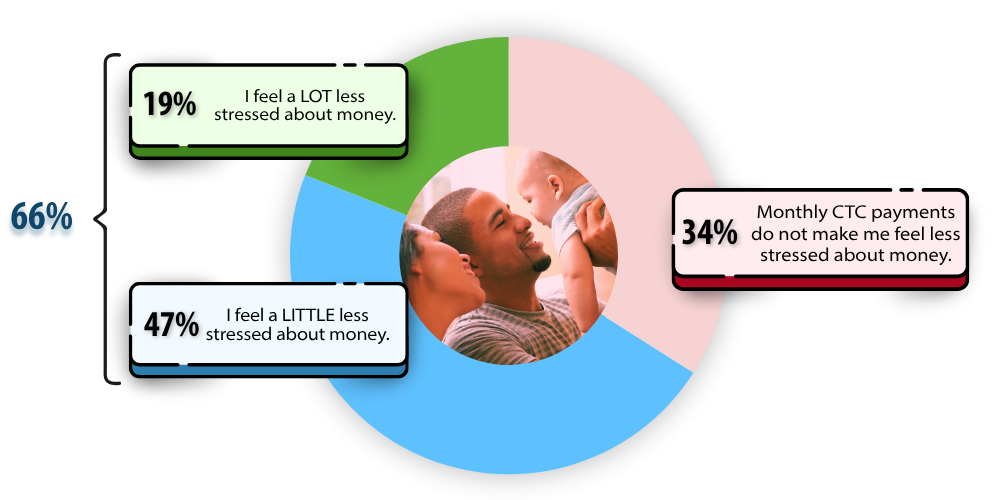

Numerous other research studies have found positive effects from cash transfers for families. CLASP, in collaboration with other partner organizations, conducted a three-part survey of over 1,000 families to assess the impact of receiving the expanded CTC payments in 2021. [9] Our surveys found that the monthly payments helped parents afford essentials—bills, groceries, and rent/mortgage payments. Nearly 70 percent of families who received the monthly payments said they reduced their financial stress [10] (Figure 1). And about one-quarter of the parents who got the monthly payments said they made it easier for them to work, or work more hours. [11] Part of the reason for this is that it costs money to maintain employment, and if a worker is one emergency away from a financial spiral, that puts them at high risk for forced unemployment. For example, if a car breaks down, the worker doesn’t have the savings to fix it, and they live in a community without reliable public transportation, how would they get to their job? One parent interviewed for the CTC survey project explained that the CTC monthly payment is what allowed them to get their car repaired.

Figure 1. A Majority of Monthly CTC Recipients Report Reduced Financial Stress as a Result of the Program:

When asked, “Which statement best matches how you feel about the monthly CTC payments?” measured in percentage of respondents who receive monthly payments

The Rx Kids program in Flint, Michigan has produced compelling findings of how universal payments for pregnant people and newborn babies can positively benefit the well-being of both generations. [12] Rx Kids provides a one-time payment of $1,500 during pregnancy and monthly payments of $500 during the first year of life. [13] All families with newborns in Flint are eligible for the payments so long as they can prove their city residency. This program has been in place since 2024 and positive outcomes have already been reported. In addition, the program has expanded to eleven pilot sites throughout the state of Michigan, including Kalamazoo, Pontiac, and certain counties in the Upper Peninsula.

When comparing the health outcomes of parents in Flint before the program began and in comparable cities, families receiving Rx Kids had positive birth weight outcomes, and reductions in premature births and neonatal intensive care unit admissions. [14] Mothers enrolled in Rx Kids also reported better maternal mental health outcomes: being less likely to suffer from postpartum depression and anxiety and more likely to report feeling loved and valued. [15]

Magnolia Mother’s Trust provides cash support for Black mothers with low incomes in Jackson, Mississippi. [16] In addition to a monthly, unrestricted cash payment of $1,000 for twelve months, the program also provides social and emotional support for participants and various supportive services. The program has a two-generation approach, also offering a 529 Children’s Savings Account for the children of participating moms. Among many positive financial and emotional well-being changes reported for the 2022-2023 cohort, the percent of moms who were employed increased after receiving the payments at a statistically significant level. [17] This is an example of one of many studies that have refuted the tired cliché of cash transfer programs disincentivizing work among participants.

These are just two of the many innovative cash transfer programs being implemented throughout the nation that are having positive outcomes for children and caregivers.

Guaranteed Income Benefits All

Everyone deserves enough cash to make ends meet. We are all better off when caregivers can afford baby formula and have time to read to their children because they don’t need to take on extra gig work to afford rent. When we choose to invest in caregivers and in babies, that promotes long-term, positive outcomes. [18] Existing public benefit programs are critical but can leave out families who are struggling because of work requirements, [19] time limits, [20] behavioral requirements, [21] and stigma. [22] Targeted cash transfers are a critical tool that policymakers must consider implementing to ensure investments in all children.

Research from the COVID-19 pandemic and from guaranteed income pilots throughout the nation, and around the globe, provides overwhelming evidence that this model works. Simply providing cash to people improves well-being, decreases parental stress, and reduces poverty. The media sensationalism of one study should not mute those critical findings. Guaranteed income works.

November 18, 2025, Washington, D.C.– Yesterday, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) released a proposal to repeal the 2022 public charge rule, which is applicable to immigrants applying for a green card, with plans to release more restrictive guidance at a later date. Without the 2022 rule in place, DHS officers would have wide discretion to make arbitrary decisions about granting a visa or green card based on a person’s current or former health and economic situation, as well as their past or potential use of a wide range of health and social service programs. By removing standardized guidance for DHS officers, the public charge determination process would be open to widespread confusion, discrimination, fear, and chaos. Once the rule is published, the public will have a 30-day comment period to provide input.

The proposed rule claims so-called cost ‘savings’ from people disenrolling from public benefits due to the chilling effect of these proposed changes. However, there is no mention of how public benefits contribute to public health and overall well-being and of the cost savings from providing preventive health care and access to nutritious food to people who cannot afford them. The proposal also aims to punish immigrants for using government support programs they pay into. Moreover, the Trump Administration even acknowledges that this rule would cause economic harm to our health care providers, grocery retailers, and farmers. Yet the administration is choosing to proceed with this rule anyway, prioritizing its crusade against immigrants over what’s actually best for the country and our economy.

CLASP is committed to ensuring that all families are able to meet their basic needs, and we will work alongside our partners to defeat this reckless public charge proposal as we did under the first Trump Administration.

In response to the proposed rule, Wendy Chun-Hoon, President and Executive Director of the Center for Law and Social Policy, released the following statement:

“This is yet another cruel attempt by the Trump Administration to sow fear and confusion among immigrant communities, deterring them from accessing critical services and supports, like seeking health care and food assistance essential to their well-being and that of their children. Providers who serve all communities will be forced yet again to struggle in navigating this ever-changing policy environment, wasting time and resources. As was the case when the first Trump Administration proposed public charge changes, this new rule will lead to millions of families missing doctor’s appointments, disenrolling from programs they are eligible for, and further isolating themselves. Children in immigrant families, including U.S. citizens, will once again face long-term developmental harms, which our country will ultimately pay the price for.”

(Excerpt) Teon Hayes, a senior policy analyst at the Center for Law and Social Policy, noted that even before the reductions, SNAP payments weren’t substantial — full benefits are $6 per person per day. “Every late payment, every overdraft fee, every high-interest-rate loan, that is just pushing someone deeper into a financial hole,” Hayes said.

The full article can be found on Inside Mortgage Finance’s website for subscribers.

The federal government may be shut down, but hunger in America hasn’t taken a break. While the nation’s attention is understandably focused on the shutdown’s immediate fallout, we can’t lose sight of a deeply consequential decision that has slipped under the radar: the final release of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s¹ (USDA) long-standing Household Food Security report.

This decision comes on the heels of sweeping, harmful cuts² to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)—cuts that will make it harder for millions of people to afford food. By eliminating the only comprehensive, government-backed survey that tracks food insecurity in the United States, the USDA is effectively ensuring that the devastating consequences of these cuts will be harder to measure and easier to ignore.

What the Report Is and Why It Matters

For nearly 30 years, the USDA’s Household Food Security Report³ has been the backbone of how hunger is measured in this country, giving the clearest and most consistent picture of who is going hungry and why. The report uses data from the Current Population Survey,⁴ a joint project between the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which reaches about 60,000 households every month through phone calls and in-person interviews. Every December, the survey adds a special set of food security questions that allow the USDA to measure how many people are struggling to afford food.

For less than $1 million a year, the government has been able to produce a report that informs more than $100 billion in nutrition funding, including SNAP, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), and school meal programs. This is data that drives real policy, helping advocates, researchers, and lawmakers track hunger over time, evaluate whether our safety net programs are actually working, and hold the government accountable to its promises. No other dataset has the same credibility or reach.

The Food Security report isn’t just a spreadsheet. It’s the foundation for how we understand hunger in America. Other national surveys⁵ touch on food hardship, but none come close in scale or depth. Even if the existing surveys were merged, it would take years to rebuild what the USDA report provided in a single release.

Despite this, the Trump Administration has dismissed the report as “redundant, costly, politicized, and extraneous,”⁶ claiming it offers nothing more than “subjective, liberal fodder.” That framing couldn’t be further from the truth. The report has consistently shown that hunger in America rises and falls with policy decisions and economic conditions, not political spin. Ending this report now, in the same moment as historic SNAP cuts, doesn’t just feel suspicious— it’s strategic.

This is a devastating loss for transparency and accountability. Without this report, we lose our ability to measure the real impact of policy decisions on people’s lives. It means the stories and struggles of millions of families facing hunger—families who are already working, caregiving, and doing everything they can to survive—will become invisible in the data. And when something isn’t measured, it becomes easier to deny that it exists.

The Historical and Systemic Context of Data Suppression

We must not ignore the truth behind ending this report. This decision is part of a long-standing pattern of restricting or eliminating data collection when it exposes inequities or challenges political narratives. Throughout history, the suppression or manipulation of data has been used to hide inequality rather than confront it.

For example, U.S. Census data has repeatedly misrepresented or erased entire communities of color. In 1930,⁷ “Mexican” was briefly listed as a separate racial category before being removed in 1940, effectively classifying Mexican Americans as white and masking the discrimination they faced. Native Americans who were not taxed were excluded from the Census until 1924,⁸ when they were granted citizenship, and many Asian and multiracial groups were not⁹ accurately counted until decades later. These omissions have distorted our understanding of poverty, health, housing, and other inequities across racial and ethnic lines.

The same pattern played out during the COVID-19 pandemic, when cases and deaths were not reported¹⁰ with racial or ethnic data, delaying efforts to address the disproportionate impact of the virus. Black, Hispanic, American Indian or Alaska Native, and other populations of color experienced higher rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths than white people. However, incomplete data collection, particularly a lack of demographic information, hid the full impact of the pandemic on communities of color.

Historically, marginalized communities are the first to be erased when data disappears. When we stop measuring hunger, we effectively make hunger invisible in the public debate, even though it continues to exist.

The Harm of Ending the Report

Ending this report right now is not a coincidence. It’s intentional. At a time when SNAP is facing some of the harshest cuts we’ve seen in decades, the timing speaks volumes.

Without this report, it becomes almost impossible to measure how many people are being pushed deeper into hunger by these recent policy changes. Even more concerning is how the USDA justified the decision, saying:¹¹

“For 30 years, this study—initially created by the Clinton administration as a means to support the increase of SNAP eligibility and benefit allotments—failed to present anything more than subjective, liberal fodder. Trends in the prevalence of food insecurity have remained virtually unchanged, regardless of an over 87% increase in SNAP spending between 2019–2023.”

That statement completely misses the point of the data, whose purpose was never to make hunger disappear overnight. Rather, it was to make sure hunger couldn’t be ignored. The report has consistently helped shape stronger nutrition programs and policy decisions that reflect reality. If hunger has remained persistent, that’s not because of the data but because policymakers haven’t done enough with what the data shows. Blaming the report for ongoing hunger is like blaming a thermometer for the fever. The numbers don’t create the problem–they reveal it. It’s Congress’s responsibility to act on what the data exposes, not to silence it.

Ignoring the realities of hunger doesn’t make them disappear; it just magnifies their consequences. The inability to consistently afford nutritious food doesn’t just affect what’s on a family’s table; it affects their health, their stability, and their futures. People living in food-insecure homes are more likely to face chronic illnesses¹² like diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, and they experience higher rates of anxiety and depression. For older adults,¹³ hunger accelerates physical decline and increases hospitalizations. For children,¹⁴ it hinders brain development, academic performance, and long-term opportunity. All of this comes at a cost not just to individuals and families, but to our entire health care system, which is already strained and overburdened. According to research from Feeding America,¹⁵ the ripple effects of hunger and poor nutrition drive up medical spending and emergency care use, especially in communities already facing systemic barriers to accessing health care.

When we stop collecting data on hunger, we’re not just losing sight of a social issue—we’re ignoring a public health crisis. By ending this report, advocates lose one of the most powerful tools we have to hold lawmakers accountable for decisions that deepen hunger. States and local agencies lose the baseline data they need to design programs that actually respond to people’s needs. And communities lose their visibility in a system that already struggles to see them clearly.

This decision will harm the very people already most impacted by systemic inequities. Communities of color continue to face disproportionately high rates of hunger because of deep-rooted barriers in housing, wages, and employment—barriers that didn’t appear by accident. Decades of discriminatory policies, from redlining and wage exploitation to unequal access to education and credit, have stripped wealth and opportunity from Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color. Those harms compound over generations, leaving families with fewer buffers against rising food costs and economic instability. Without reliable federal data, those disparities become easier to ignore and harder to address. Immigrant families, particularly mixed-status households, risk becoming even more invisible. Fear and misinformation already keep many from applying for food assistance, and removing the data that captures their struggles erases them from the national conversation entirely. Tribal and rural communities, which often experience the highest rates of food insecurity but have the least access to local research or advocacy infrastructure, will see their experiences further minimized or dismissed. And women-headed households—especially Black and Latina single mothers—will be among the hardest hit. Without consistent, credible data to track these inequities, the stories behind the statistics fade from view, and policy debates lose the grounding they need to reflect real life.

The USDA’s claim that this report is “redundant” simply isn’t true. No other survey offers the same breadth, history, or reliability. Alternative sources like food bank surveys or limited state data are valuable but not nationally representative—they cannot replace this federal benchmark.

This isn’t bureaucratic streamlining; it’s data suppression disguised as efficiency. And the outcome is the same every time: the people closest to hunger—families with low incomes, people of color, disabled and older adults, and rural communities—are made invisible just when the nation needs to see them most clearly.

Call to Action

The USDA must reinstate the Household Food Security Report and its data collection immediately. Every day that this report remains silent, the truth about hunger in America slips further out of sight.

Hunger cannot be solved if it is hidden. This report isn’t just numbers on a spreadsheet—it’s a reflection of real people, real families, and real lives. It tells the story of parents skipping meals so their children can eat, of seniors stretching fixed incomes, and of workers who are employed full-time but still can’t afford groceries. When we stop collecting that data, we’re not just losing information, we’re choosing not to see.

Lawmakers, advocates, and the public deserve to know the truth about how many people in America, one of the richest countries in the world, are going without enough to eat. Data is accountability. It’s a mirror that forces us to confront what’s broken and gives us the tools to build something better, if we choose to.

Transparency isn’t a political choice, but a moral one that should be upheld no matter the administration. If we truly believe in building a nation where everyone can thrive, then we must have the courage to face the facts, no matter how uncomfortable they are. Restoring this report is not just about research—it’s about restoring the visibility and dignity of the millions of people whose hunger should never be invisible.

Endnotes

This statement can be attributed to Wendy Chun-Hoon, executive director of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

Washington, D.C., October 28, 2025—With the federal government shutdown nearly a month old, it is important to note that the chaos, dysfunction, and harm to families and workers caused by the shutdown is a result of deliberate policy choices by the Trump Administration and Republican leadership in Congress.

The stalemate created by the refusal of Congressional leadership and the Trump Administration to come to the table is unnecessarily threatening food assistance, access to Head Start, and other important programs families rely on and forcing millions of people to soon face increasing health care costs.

The government shutdown was entirely avoidable. The lawmakers who voted for H.R. 1 in July actively chose not to extend enhanced premium tax credits to keep health care more affordable, despite knowing that they would expire this year. Instead, lawmakers passed a bill that costs trillions of dollars to pay for tax breaks to the wealthiest and corporations and increased funding for harmful ICE immigration enforcement, all while cutting Medicaid and SNAP and making marketplace health insurance unaffordable for millions of U.S. citizens.

The continued government shutdown has resulted in thousands of federal workers needlessly losing their jobs or not receiving paychecks this month. However, some federal employees like ICE agents are still getting paid to carry out indiscriminate immigration enforcement actions, resulting in more than 170 U.S. citizens being detained. At the same time, construction recently began on a $300 million White House ballroom. This country’s leadership is prioritizing terrorizing families and executive mansion renovations over ensuring that individuals and families receive the support and benefits that they need to thrive.

With the government shutdown approaching November, the funding is at risk for programs that families rely on, like SNAP, WIC, and Head Start. SNAP, which allows approximately 42 million people to afford food, and WIC, which provides nutritional support, education, and other forms of assistance for pregnant women and parents with children under 5 years old, are two of the most effective tools we have to prevent food insecurity, stabilize local economies, and support public health. Suspending or delaying benefits would have devastating consequences for millions of households across the country and will further strain food pantries that are already stretched thin. Head Start and Early Head Start play a valuable role in providing early education to hundreds of thousands of families every year; if the shutdown persists into November, federal grants for more than 100 Head Start programs across the country will be cut, threatening access for more than 65,000 families that depend on the program. Moreover, millions of families will begin to see their cost of health insurance more than double next year.

Congress must extend the ACA enhanced premium tax credits, reopen the government, and deliver full coverage of benefits and access to programs that people rely on. Again, this is a manufactured crisis. Despite their statements to the contrary, the administration clearly has the means to use authorized USDA funds until Congress acts to ensure families, seniors, workers, and millions of other people don’t go hungry in November.

On October 6, 2025, Teon Hayes presented the workshop “Cultivating Resilience: Creative Expression for Advocate” at the Prosperity Summit. The session focused on using painting and gardening as tools for wellness and creative expression.

This statement can be attributed to Wendy Chun-Hoon, executive director of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

Washington, D.C., October 1, 2025 – After Congress failed to pass a budget for Fiscal Year 2026 by the September 30 deadline, the federal government has shut down. Budgets are moral documents, and Congress should be focused on funding the government in a way that supports children, workers, families, and communities across the country. This includes extending programs that continue to make health care affordable for millions and ensuring that children and families receive the assistance they’re eligible for and need to thrive.

Voters across the country elect their Members of Congress and entrust them to do their jobs. The most basic function of Congress is to pass a budget each year. In a functioning government, this budget would be free from interference by a presidential administration. Instead, the administration is manufacturing chaos and dysfunction to continue to weaken the institutions families rely on to survive.

As conversation and work continue around passing an agreement to fund the government, CLASP’s focus remains on communities being pushed to the margin, workers paid low wages, children, immigrants, communities of color, and people and families living on low incomes. Their safety, security, and well-being should not be held hostage by a dysfunctional government.

Updated April 2, 2025, by Priya Pandey; Spanish version added September 2025 (see link below)

Originally published in 2019 by Rebecca Ullrich and updated in February 2022 by Alejandra Londono Gomez

Early childhood programs play an important role in the lives of young children and their families. But in our current political climate, families across the country are questioning whether it’s safe to attend or enroll.

In January 2025, the Trump Administration rescinded the Biden Administration’s guidelines for Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection enforcement actions in certain “protected areas.” Immigration enforcement actions had previously been restricted at or near these locations, which include early childhood programs such as licensed child care, preschool, pre-kindergarten, and Head Start programs.

In response, we have updated “A Guide to Creating ‘Safe Space’ Policies for Early Childhood Programs,” which gives practitioners, advocates, and policymakers information and resources to design and implement “safe space” policies that safeguard early childhood programs against immigration enforcement, as well as protect families’ safety and privacy. The guide also includes sample policy text that early childhood providers can adapt for their programs.