CLASP

The Center for Law and Social Policy

About CLASP

The Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP) is a national, nonpartisan, anti-poverty organization advancing policy solutions that work for people with low incomes and people of color. We advocate for public policies and programs at the federal, state, and local levels that reduce poverty, improve the lives of people with low incomes, and advance racial, gender, and economic justice. Our solutions directly address the barriers that individuals and families face because of race, ethnicity, low income, gender, immigration status, and involvement with the carceral system.

Over more than 50 years we have kept our vision alive through our trusted expertise on policy and strategy, deeply knowledgeable and committed staff, partnerships with directly impacted people and grassroots leaders, and bold, innovative, and inclusive approaches to economic, racial, and gender justice.

At this extraordinarily important moment for the United States, CLASP is actively defending against unprecedented and relentless assaults on the people and policies at the core of our agenda. We are doing so through a mix of congressional advocacy built on our vision, relationships, and deep knowledge; administrative advocacy to fight against the unabating attacks on programs and policies; state-level change, by generating impactful ideas in collaboration with state officials and advocates; and a powerful vision put forward together with on-the-ground leaders.

About the Education, Labor, and Worker Justice Team

CLASP is uniquely positioned within the broader policy advocacy world in our focus at the intersection of jobs, postsecondary education, workforce, adult education, and public benefits – and because we center the experiences of workers and students with low incomes and communities of color in our policy advocacy. Key to our effectiveness is our ability to toggle between federal and state policy and implementation, our core commitment to workers paid the lowest wages—often, women of color—and our trusted relationships with public officials, advocates, and grassroots organizers.

The Education, Labor and Worker Justice (ELWJ) team is laser-focused on ensuring that all jobs are good jobs and all workers—and would-be workers—have ongoing access to education and training opportunities with a focus on those engaged in work paying low wages. The team works to dismantle and reform systemic and institutional failures in the labor market and workforce system that perpetuate widening gender and racial wage and wealth gaps.

The ELWJ team leverages CLASP’s deep expertise on worker benefits, worker protections, worker voice, worker rights advocacy, labor standards enforcement, and racial equity with our crucial role in advancing job creation, workforce development, and postsecondary education policies that uplift people with low incomes who have been historically marginalized by systemic racism, economic exclusion, and immigration-related barriers. The Team Director will lead the ELWJ team.

CLASP has a long-standing commitment to workforce development, foundational skills development, and postsecondary education as key strategies to advance economic mobility, increasing credential attainment, advancing skills, and providing work experience to individuals who face structural barriers to employment. Staff play a leadership role in advancing crucial policies for workers and students of color and those in industries that pay low wages. Working closely with coalition partners, CLASP has been central to shaping the national conversation on addressing the changing nature of low-wage work and addressing systemic barriers to employment and education.

Position Summary

The Director will play a central leadership role in shaping and advancing CLASP’s vision for racial, gender, and economic equity through transformative worker- and student-centered policy solutions. As a key member of the organization’s Leadership team, the Director will collaborate with colleagues to set CLASP’s strategic agenda and cultivate a strong, equity-driven organizational culture. They will mentor staff, set clear performance expectations, develop staff leadership, and foster a collaborative, mission-aligned work environment.

The Director will serve as a leading voice for CLASP’s advocacy on worker benefits, labor protections, job quality, and workforce equity—engaging with funders, policymakers, and national and grassroots partners. They will guide strategy and partnerships that elevate the voices of workers and dismantle systemic labor market barriers for people with low incomes who have been historically marginalized by systemic racism, economic exclusion, and immigration-related barriers. This role includes thought leadership on federal and state policy, cross-team collaboration within CLASP, and strategic fundraising that advances the organization’s mission. The Director will bring a bold vision for inclusive economic justice, leveraging CLASP’s expertise to expand access to good jobs, high-quality postsecondary education, and equitable labor standards enforcement.

Requirements

- Substantial experience at a leadership level as an advocate for postsecondary education, workforce development, good jobs, and/or job quality policies that center people who have been historically marginalized by systemic racism, economic exclusion, and immigration-related barriers, whether in an advocacy organization, as a legislative staffer, through leadership on these issues within government or with an employer, through lived experience, or several of the above.

- Deep policy knowledge and recognized expertise in relation to paid family leave/paid sick days, subsidized jobs, expanding worker power and ownership, worker protections, and related policies strongly preferred.

- Demonstrated ability to effectively recruit, supervise, and lead a diverse team that includes both senior and junior members.

- Skilled at managing and motivating teams, supporting staff growth, and creating a culture of accountability and care.

- Proven ability to identify and develop advocacy strategies.

- Demonstrated experience in effective writing and speaking to a variety of audiences.

- Successful record of initiating and cultivating relationships with partners. Existing relationships with job quality advocates, labor unions and other worker advocates, Hill staff, legal advocates, civil and immigrant rights leaders, and public officials working on job issues are a plus.

- Demonstrated success in fundraising and managing relationships with funders is strongly preferred but not required.

- Demonstrated commitment to improving the lives of people with low incomes, to racial justice, and to CLASP’s vision, mission, and values.

- Demonstrated commitment to addressing racial discrimination and immigration policies that limit access to quality jobs and economic advancement.

- Centers equity with an understanding of barriers faced by people with low incomes impacted by systemic injustice.

- Brings significant leadership and people management experience and thrives in collaborative, team-oriented environments.

- Demonstrates a strong intersectional analysis in their work, with particular awareness of the issues and hurdles impacting people with low incomes who have been historically marginalized by systemic racism, economic exclusion, and immigration-related barriers.

- Skilled in leading partnerships with community-based advocates.

- Collaborative leader who enjoys working closely with other leaders and experts as part of a tight-knit team

- Brings experience in national advocacy and strategic partnerships, broadly, with advocacy experience with Congress.

- Passionate, creative, and effective advocate and leader to build on CLASP’s history and this extraordinary moment in time to get major new policies enacted and implemented.

- Has experience with federal advocacy and strong relationships with key partners across labor, education, and equity movements.

- Effective communicator, fundraiser, and mentor with a track record of supporting staff and securing resources.

- Bachelor’s degree required and a minimum of 10 years of related experience or a master’s degree or other advanced degree and 7 years of related experience.

- At least 5+ years of experience supervising and managing diverse teams, with a demonstrated commitment to inclusive and effective leadership. Proven ability to effectively lead staff at various career stages—including both senior and early-career professionals—in a hybrid work environment.

- Candidates must be based in the Washington, D.C. area or be willing to relocate.

UNION ENVIRONMENT AND POSITION STATUS

CLASP is a unionized organization, but this position is not part of the bargaining unit. Employees are represented by CLASP Workers United (OPEIU, Local 2). CLASP values collaboration, fair labor practices, and constructive engagement with the union. We have just finalized our first Collective Bargaining Agreement, which will be in effect until May 2027.

Compensation:

Salary Range: $150 – 160K

Salary is commensurate with experience. CLASP offers exceptional benefits, including several employer-paid health insurance options, dental insurance, life and long-term disability insurance, long-term care insurance, a 403(b)-retirement program, flexible spending accounts, and generous vacation, paid sick leave, paid family and medical leave, and holiday schedules.

Application Process: Please apply here and include a cover letter with your submission. Applications will be accepted until the position is filled. NO PHONE CALLS, PLEASE.

By Juan Carlos Gomez

Families are already struggling with higher costs of living, and the Senate’s budget reconciliation bill will only increase the costs of health care, food, and everyday necessities. The bill’s text affirms that at its core, this is legislation that will drain money from the families with the lowest incomes in order to benefit the wealthy.

Millions Could Lose Health Care, Food Assistance, and Economic Stability

The bill would make the largest cuts to Medicaid and SNAP in history, dismantling the provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace that make it effective in providing affordable health coverage and many free health care services to millions. The proposed language in the Senate makes even deeper cuts to Medicaid and, in total, could cause up to 16 million people to become uninsured. These cuts will cause widespread harm and impact essential workers, like child care providers, who rely on Medicaid due to a lack of access to benefits and low-paying jobs. When Congress tried to repeal the ACA in 2017, they failed because it was deeply unpopular and people understood that weakening the Marketplace would leave millions without affordable health coverage.

Burdensome Work Requirements Are Cuts by Another Name

Burdensome Work Requirements Are Cuts by Another Name

Additionally, the drastic cuts to SNAP could leave over 8 million people with little to no food assistance, harming our economy. Every dollar that goes to SNAP results in up to $1.80 in economic ripple effects that benefit farmers, grocery stores, truck drivers, payment processors, food manufacturers, and others as the funds circulate in the local economy. Less funding for SNAP means families are spending less, impacting more than 250,000 SNAP-authorized retailers nationwide.

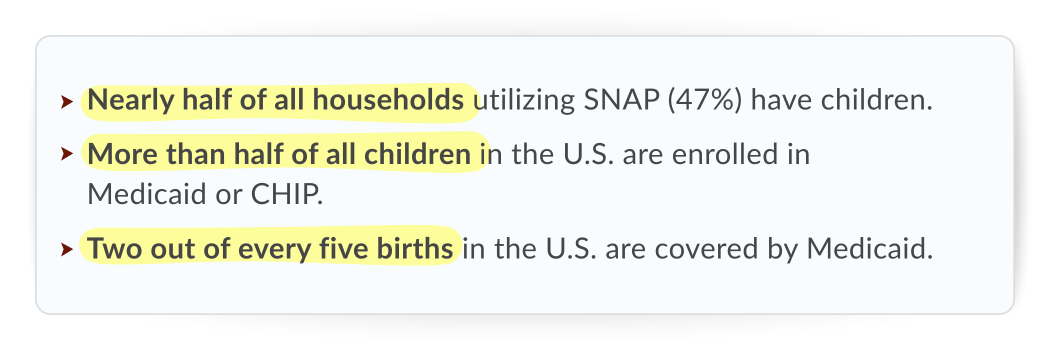

The House-passed bill and Senate proposal would create the first mandate for states to implement work requirements in Medicaid programs and make existing SNAP work requirements even more burdensome. Decades of research show that work requirements don’t increase stable employment or economic security. Instead, they lead to large drops in program participation by creating complex, burdensome paperwork that eligible people often can’t navigate. This causes people to lose benefits not because they’re ineligible, but because the system becomes too difficult to access. These policies are especially harmful to people in low-wage jobs, caregivers, and those with health conditions, many of whom already face systemic barriers like discrimination, lack of child care, or unreliable transportation. Work requirements are simply cuts to life-saving programs under a different name.

Millions of Children and Families Will be Barred From Economic Supports

While the Senate bill increases the maximum Child Tax Credit (CTC) to $2,200 per child, it does not make the credit fully available to families with little to no earnings. Under the Senate bill, 17 million children will continue to be left out of receiving the full CTC. Additionally, families that do not have at least one parent with a Social Security number would be barred from accessing the CTC under the Senate bill. This would restrict access to the CTC for 2.6 million citizen children.

The bill would make the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) more difficult to claim for 17 million families with low to moderate incomes by adding a burdensome pre-certification requirement. This would create needless red tape and stress for families with children as they file to claim the EITC. Lawmakers have decreased funding and staffing for the IRS, meaning the agency will have less capacity to provide adequate customer support to parents as they navigate this new policy.

Attacks on Immigrant Communities Will Have Ripple Effects for All Families

Undocumented immigrants are already ineligible for the CTC, Medicaid, Medicare, Affordable Care Act coverage, and SNAP. This legislation bars immigrants who are primarily authorized for humanitarian reasons to be in the United States, like refugees, asylees, and domestic violence survivors, from accessing these programs; in some cases, even green card holders could be blocked. These policies will impact both adults and children: approximately 40 percent of individuals granted refugee status and asylum in FY23 were children.

On top of further limiting immigrant access to essential benefits, this legislation increases funding for mass deportation. Immigrants–including those with authorization–and U.S. citizens alike have been subject to immigration enforcement actions without due process. Over 5 million children have at least one undocumented parent they are at risk of being separated from, and 2.6 million citizen children in the U.S. have only an undocumented parent(s) and are at risk of being left with no one to care for them due to their parent’s detention or deportation. As the Trump Administration continues to strip immigrants of their legal statuses and eligibility for support, the number of children who are harmed by immigration enforcement will grow, the vast majority of whom are U.S. citizens. Fears of immigration enforcement will also cause a chilling effect even among immigrants who qualify for food and health insurance assistance. They will disenroll or not enroll in these lifesaving programs, impacting access for their children and their well-being.

Tax Breaks for the Wealthy Reduce Funding That Supports Children and Families

This bill centers wealthy families by offering tax breaks for the rich while cutting and eliminating essential programs that meet the needs of families. These significant tax breaks mean less revenue to support programs that families rely on and undermine their basic needs. Decisions about investments in programs will come with challenging tradeoffs and will, without a doubt, leave families and children, especially those with the lowest incomes, out to dry. Programs like child care, Head Start, and services for people with disabilities will suffer, and positive progress will be lost.

States and Our Health Care System Will Bear the Burden as Federal Government Withdraws Support

Children and families’ needs for health care and food do not go away just because the federal government chooses not to fund them. Instead, states and local governments–which already have strained budgets–will have to figure out how to implement new, burdensome provisions of the bill and deal with cuts to funding in order to support their residents by shifting costs from other important needs or forcing families off of Medicaid, SNAP, and other essential programs. This bill creates impossible situations for states, forcing them to make decisions about which basic needs they are able to support for the very same families.

As millions of people lose health insurance, the cost of uncompensated care skyrocket, causing tremendous strain on our health care system. This, in turn, could cause hospitals and health care centers to shutter services or close altogether. This will be especially devastating for rural communities where children and families already face barriers to accessible health care, and over 4 in 10 hospitals are already losing money.

The Budget Reconciliation Bill Sets Students, Workers, Children, and Families Up to Fail

Students Will Likely Experience Increased Financial Pressure

Education-related cuts include severe restrictions on federal student aid for students with low incomes at a time when many students already struggle with the increasing cost of pursuing a college degree. Nearly 4.4 million Pell Grant recipients would see their award amounts reduced, and new student loan borrowers would be forced to make larger payments even if they are unemployed or struggling to pay bills. These provisions will drive more borrowers into defaulting on their loans and, as a result, have their CTC and EITC refunds seized. For universities, these restrictions would compound through states being potentially forced to cut education spending to make up for the loss of federal funding for health care and other social services. Institutions would also be forced to no longer offer access to federal student loans, close certain academic programs, or shutter their campuses due to the bill requiring colleges to pay a percentage of unpaid debt.

Workers Face Pay Cuts, Weakened Unions, and Job Insecurity

Workers will see lower wages with rising costs, including for utilities, food, and other necessities in the household. With the continued attacks on unions, all workers face an increase in job security and risk their health and safety at the workplace. And while civil servants have already faced numerous challenges this year due to rounds of layoffs, this bill would cut take-home pay for new civil servants while undermining their workplace rights and limiting federal labor unions’ ability to protect their members.

On top of reducing take-home pay for civil workers, this bill also places a 10 percent tax on labor unions for solely existing in the workplace. Under this bill, it will be increasingly challenging for employees to contest unlawful dismissals or discrimination, and the financial repercussions will be considerably greater for workers aiming to maintain their rights. These changes will affect federal agencies’ ability to retain and recruit workers while placing additional financial burdens on federal workers, their families, and their children.

Young Children and Families Will Not Have Access to Necessary Child Care and Early Education Support

While a child care crisis persists in our country, this bill does nothing to support access to affordable and accessible child care for children and families. While the bill includes a number of tax incentives and credits related to child care, it does not address the true needs of children and families. In fact, even these tax provisions would not benefit families with low incomes, as they are targeted at employers, higher-income jobs, and families with tax liability. It puts no effort into making child care more affordable for the children and families who need it most or supporting the undervalued and underpaid child care workforce.

Resources on budget reconciliation:

- CLASP’s Defending Public Benefits: A Playbook for Policymakers

- Children Thrive Action Network’s Budget Reconciliation Brief

- CLASP’s Infographic: It’s a Cut to Medicaid No Matter What You Call It

By Christian Collins and Sarah Erdreich

As Congress works to advance the proposed budget reconciliation bill of 2025, CLASP’s series “The 2025 Budget Reconciliation’s Impact on People with Low Incomes” will examine the policies put forward that have particular resonance for the children, families, and communities with low incomes. This is the second blog in the series.

On April 29, the House Education & Workforce committee marked up its portion of the House’s reconciliation bill. The committee voted to advance the legislation, which makes drastic changes to Department of Education programs and initiatives, by a party-line vote of 21-14.

Republicans claim that their legislation will save over $330 billion and make federal education policy more effective. But the details of this plan make it clear that the GOP is sacrificing the future of the country for working people to fund planned tax cuts for the ultra-wealthy. Below, we examine some of the most concerning proposals.

Pell Grants

The committee’s bill would increase funding for the Pell Grants program by $10.5 billion from fiscal year (FY) 2026 to FY2028. However, students would need to take at least 15 credit hours each semester to maintain eligibility, up from the current requirement of at least 12 credit hours per semester. This change would place an unnecessary burden on students who also work, parent, or have other time-consuming responsibilities in addition to pursuing a degree in higher education. As a result, fewer students would be eligible for Pell grants.

Student Loans and Financial Aid

The bill also changes how student loan programs would operate, including ending subsidized loans altogether and causing loan interest to accumulate immediately. In addition, schools would be required to repay a portion of their students’ loans if the students miss payments. Moreover, federal aid would be eliminated if the number of students who miss payments is considered too high. According to the committee’s own data, 98 percent of institutions would have to make these payments, and 75 percent would experience a net loss of federal funding, even factoring in the performance-based incentives and grants included in this bill.

Republicans claim that this will impel schools to put more effort into ensuring their graduates find high-quality jobs. This assertion ignores the fact that schools with higher populations of students having low incomes are more likely to need student loans in the first place, will be disproportionately at risk of losing federal funding, and may be reluctant to even consider accepting students who need aid.

It is also notable that this Republican proposal would change the way that financial aid eligibility is determined. Currently, the amount of federal aid a student receives is based on the cost of attending the school in which they plan to enroll. This new proposal would base the amount on the median cost of attending a similar program nationally. However, no clarity was offered as to how the Department of Education will determine median costs; if they have the workforce to do this, given widespread cuts at the department; and how this would be enforced if the GOP makes good on Donald Trump’s oft-stated vow to dismantle the department altogether.

Loan Forgiveness

Access to all existing income-based plans would be eliminated and replaced with a new “Repayment Assistance Plan,” which could cause borrowers to see a disproportionate spike in their monthly payment whenever they move across the proposal’s arbitrary income thresholds. The bill also proposes collapsing the current standard, graduated, and extended repayment plans into a single “standard” plan with varying repayment lengths based on a borrower’s loan balance. These changes would leave borrowers paying more per month, becoming more likely to land in defaults, and ultimately affect the economic security of millions of borrowers.

The Republican proposal on behalf of the House Education & Workforce Committee is nothing more than a brazen sacrifice of our higher education system to further enrich the wealthy through tax cuts. These measures do not increase educational access for students, make investments into institutions that reflect their role as a public good, or adequately address the growing national concern around student debt. Republicans claim that American higher education needs fiscal reform to maintain future sustainability, but they have only presented policies meant to decimate the system and ensure that only students who are already wealthy can earn degrees.

By Juan Carlos Gomez and Sarah Erdreich

As Congress works to advance the proposed budget reconciliation bill of 2025, CLASP’s series “The 2025 Budget Reconciliation’s Impact on People with Low Incomes” will examine the policies put forward that have particular resonance for children, families, and communities with low incomes. This is the first blog in the series.

On April 30, the House Judiciary Committee met to mark up its portion of the GOP’s proposed reconciliation bill. During the nine-hour session, Democrats offered amendments to, among other things, prevent the deportation of U.S. citizen children, ensure that children have access to counsel, and prevent funds from being used for immigration enforcement activities in elementary schools—while Republicans remained largely silent. All of these amendments failed, and the committee voted 23-17 along party lines to advance the legislation.

As it stands now, this legislation will significantly increase the authority of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); expand detention facilities, including family detention facilities; and impose exorbitant fees for immigrants who are trying to stay in or adjust their status in the United States. All of these policies are harmful not just for immigrants and their families, but to the country as a whole.

CLASP research from the first Trump Administration showed how deeply enforcement activities negatively impacted children. Educators and parents observed high rates of depression, anxiety, and fear among children and increased housing instability and economic hardship among families. This, in turn, affected the communities in which immigrant families lived and worked. Allowing ICE to conduct enforcement activities in spaces where young children are present will only destabilize families and communities that are already reeling from the administration’s relentless and indiscriminate assault on immigrants, mixed-status families, and U.S. citizen children.

Likewise, the expansion of family detention means that children could be indefinitely detained, and unaccompanied children could be detained for long periods of time. No amount of detention is appropriate for children, and this expansion does not comply with decades of policy to ensure protections for children in federal custody. The expansion also shows no consideration for victims of trafficking, who would not be screened and given appropriate services.

The legislation’s inclusion of steep fees also represents a wealth test for immigrants, their families, and their communities. These fees will be a barrier to reuniting unaccompanied children with their families, and will also make it difficult for eligible immigrants to apply for asylum, adjust their status, and keep their work permits, ultimately denying people peace of mind and the ability to provide for their families.

We are only at the beginning of the markup period, and any reconciliation bill that passes the House will still have to make it through the Senate. But it is worth noting that the GOP is intent on increasing funding for immigration enforcement and included $51.6 billion for a border wall and other resources for Customs and Border Protection in the House Homeland Security markup. This increased funding comes at the cost of cutting programs U.S. citizens benefit from, such as Medicaid and SNAP, and leaving millions of children, families, senior citizens, and disabled individuals without health insurance and access to food.

By Jeff Brumley

(Excerpt)

“Another alarming aspect of the text is its proposal to significantly increase the capacity of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to apprehend and deport immigrants, said Rricha deCant, director of legislative affairs at the Center for Law and Social Policy.”

By Suzanne Wikle

After months of rumors and speculation about how Republicans in Congress will meet their goal of cutting upwards of $880 billion from Medicaid in the next ten years, more specifics about the cuts are coming into focus. Reporting on April 29 indicates the following cuts are likely in the Republican plan:

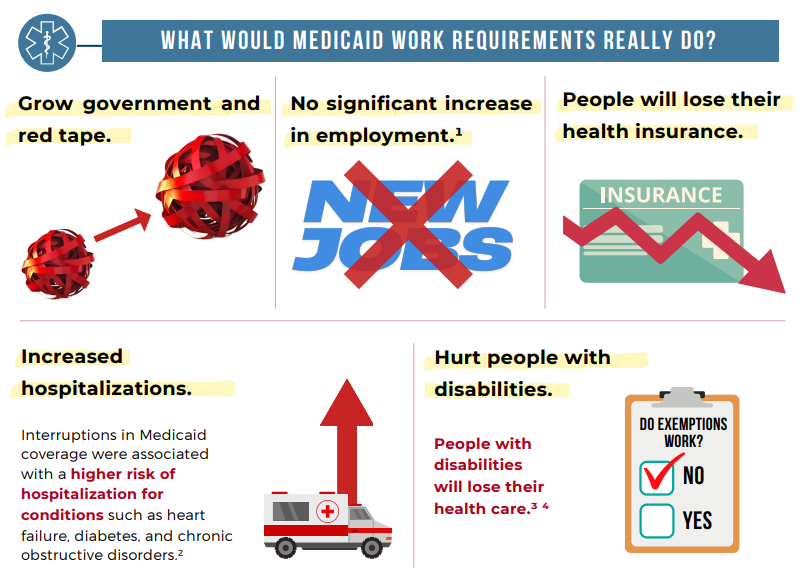

“Work requirements”

Implementing so-called “work requirements” would change eligibility for certain adults, requiring them to prove employment or other criteria before enrolling. This change in eligibility grows government and red tape, causing a significant increase in paperwork being turned in by applicants and processed by the state; it’s also worth noting that when this has been tried in other programs, the primary results are disenrollment among people who are likely still eligible and no increase in employment.

Adding “work requirements” is one of the most inefficient changes that can be made to Medicaid. The end result will be the risk of lost coverage for up to 36 million people and an increase in both the government’s workload and the cost to process eligibility and applications, while providing no meaningful uptick in employment. If the goal is to strip people of their health insurance by overwhelming them with paperwork requirements, then this will “succeed.” I suspect that is the goal, because the evidence is clear that eligible people will lose their health insurance.

Eliminating eligibility for legal immigrants

Let’s be clear: undocumented immigrants are not eligible for Medicaid that draws down federal funds. Full stop. Not eligible.

A limited group of immigrants in the country legally are eligible. Legal permanent residents eligible for Medicaid usually must wait five years before they can enroll for coverage. Revoking eligibility for green card holders will immediately leave families without access to health coverage, including pregnant women and children.

There is no sugarcoating this—if this eligibility change happens, people will immediately lose their health insurance. This likely includes people working in the care economy, including home health care and child care, and other low-income sectors that support our communities.

Per capita caps

Enacting a per capita cap model would be a drastic financing change to Medicaid. States currently know that the federal government will pay a certain share of Medicaid costs. This model has worked well for 60 years. A per capita cap model would instead give states a set dollar amount per enrollee, and then the states would be responsible for all other costs.

Per capita caps have not been tried in any human service programs.

Creating a radically different financing model for a program the size of Medicaid is incredibly risky. It’s too much, too fast.

About 20 percent of Americans are insured by Medicaid, making it a central part of our entire health care system. Reducing federal dollars to states through per capita caps will shift costs to states, which will be unable to backfill the entire loss of federal funds. States will be left with impossible decisions and are likely to reduce eligibility, cut provider payments, and decrease benefits. The net result is people losing their health care and our entire health care system losing a significant amount of funding, which means hospitals and health care facilities will close, providers will be overburdened, and more people will get sick.

Mandating more frequent eligibility checks

This is another red tape and bureaucratic option. Federal rules already require people to report changes in eligibility such as income or family size, and many states do data checks behind the scenes to monitor eligibility. Mandating more frequent eligibility checks will clog eligibility systems, increase paperwork for state eligibility workers and people insured by Medicaid, and make it more difficult for eligible people to stay enrolled. The data is clear that increasing administrative burdens like this decreases access to programs and disproportionately hurts Black and Hispanic enrollees who are more likely to hold multiple jobs or work in the gig economy, making it even more burdensome to turn in all the right paperwork.

Collectively, these proposed cuts to Medicaid end up “saving” federal dollars because they cut people’s eligibility, increase red tape so it’s too difficult for eligible people to enroll, and shift costs to states. If enacted, the outcome is predictable. People will lose their health insurance, doctors and other providers will see reduced payments, and our entire health care system will suffer.

Share with your network:

April 11, 2025 – Washington, D.C. – The Board of Trustees of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP) announced today that it has chosen Wendy Chun-Hoon as the organization’s next president and executive director. She will assume leadership of the national anti-poverty and racial justice organization on May 15, 2025, succeeding Cemeré James who has served as the interim executive director of CLASP since January 2025.

“Wendy brings decades of leadership and experience across the range of issues that CLASP addresses,” said David Hansell, chair of CLASP’s Board of Trustees. “All of us on the Board are delighted to welcome Wendy, who brings enormous skills as an advocate and leader, a demonstrated commitment to our mission and values, and the enthusiasm and passion needed to meet this critical moment. Under Wendy’s leadership, CLASP will continue playing a vital role in addressing the unprecedented assaults on the public policies that support economic security for all people who are marginalized in this country.”

Chun-Hoon most recently served in the Biden Administration as Director of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau from 2021-25. Prior to that, she was executive director of Family Values@Work, a national network of grassroots coalitions in 27 states fighting for care policies and workplace rights such as paid sick and safe days, family medical leave insurance, and child care. Her experience also includes working in state government as chief of staff to the Maryland Secretary of Human Services; in the philanthropic sector at the Open Society Foundations, where she worked on poverty alleviation; and at the Annie E. Casey Foundation, where her portfolio included public benefit programs.

Beyond her work experience, Chun-Hoon’s values align closely with CLASP’s mission to advance racial and economic justice, as she has spent her career fighting to end the marginalization of women and communities of color and to ensure economic security for all. Her deep commitment to equity, inclusion, and social justice makes her an ideal leader to continue CLASP’s work of dismantling systemic barriers and advancing meaningful change.

“CLASP has long been a leader in shaping policies that create pathways to economic security,” said Wendy Chun-Hoon. “I am deeply honored to join this remarkable organization and its dedicated team. As we face increasing challenges, my focus will be on expanding our advocacy efforts, building strategic alliances, and ensuring that CLASP’s work is guided by the diverse needs and voices of the people we serve. Together, we will continue to advance a bold, inclusive vision for racial, gender, and economic justice.”

“This moment calls for a clear-eyed view of the barriers to economic and racial justice and solutions at the scale of the problem,” said Julie Su, former U.S. Secretary of Labor. “There is no one more effective to lead that work than Wendy Chun-Hoon. Wendy is that rare person who combines great vision with concrete strategies and the ability to inspire bold action. I have seen this up close as I got to work side by side with her at the Department of Labor to invest in Black women-led organizations, produce research on the need for child care and drivers of pay inequity, and give women all across the country a real shot at economic security. Wendy’s leadership will be transformative for CLASP and the people and communities CLASP serves.”

“In uncertain times, we turn to values-driven leaders to create critical pathways forward that respect and recognize the power of lived experience and policy solutions that will advance equitable opportunity for all and ensure no person, family, or community is left behind or excluded. Wendy Chun-Hoon brings a proven track record of leadership, that spans the public, social, and philanthropic sectors, to CLASP, one of our country’s most essential policy anchor organizations,” said Anne Mosle, Vice President at the Aspen Institute and Founder & Executive Director of Ascend at the Aspen Institute. “With Wendy at the helm, the next chapter of CLASP’s mission-driven work will build bridges and accelerate policy innovation from the federal to state and local level. CLASP and Ascend at the Aspen Institute share the North Star of creating a more equitable future for families with low incomes, and I look forward to our organizations expanding our collaboration under Wendy’s leadership.”

“The CLASP team and Board of Trustees also extend our deepest gratitude to Cemeré James for her leadership as interim executive director. Under her guidance, CLASP has navigated a transition period with resilience and a continued commitment to our mission,” said Hansell.

CLASP is a 55-year-old national, nonpartisan nonprofit that focuses on economic, social, and racial justice. We work with federal, state, and local policymakers, advocates, and partners to advance policies that reduce poverty, improve the lives of people with low income, and create pathways to economic security for everyone. Our work is rooted in a belief that poverty in America is inextricably tied to systemic racism. The organization has been on the front lines of fighting back against harmful administrative and legislative proposals—particularly those from the current and prior Trump administrations—and advancing a bold and practical vision.

###

This statement can be attributed to Rricha deCant, director of legislative affairs at the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

April 10, 2025, Washington, D.C. – Today, the U.S. House of Representatives approved a budget resolution bill by a vote of 216-214 that was passed by the Senate last week. Its passage highlights the willingness of Congressional leaders to fund tax breaks for the rich and corporations and drive up the deficit through massive Medicaid cuts of $880 billion and SNAP cuts of $230 billion.

The proposal would also slash other public benefit programs that people with low incomes rely on. Instead of passing a budget resolution that would help families grapple with rising costs in an already chaotic economy, Congressional leaders are making it more difficult for families, children, and workers to have access to health care, food, and other essentials.

This measure now opens the door for Congress to write a budget reconciliation bill that could have far-reaching impacts on the lives of millions of Americans for decades to come.

By Ashley Burnside

As we anticipate Tax Day, the April 15 deadline for Americans to file their annual tax return, many households are waiting for their refunds, which will include critical tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC). Although the wealthy can find ways around paying taxes, the tax filing process should be designed to ensure that everyone pays their fair share. That’s because the revenue from our tax returns is reinvested into critical public goods that we all rely on, like public schools and roads.

But this year, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is under threat, and the agency will have less bandwidth and fewer resources to process tax returns and provide support to the taxpayers who need it. The proposed IRS layoffs and funding cuts to the agency will harm taxpayers and hurt our economy. And the data requests for access to payment systems by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) are a threat to the security and protection of Americans.

IRS Funding and Staffing is a Critical Investment to Help Americans File Their Taxes

Having a fully staffed and funded IRS is important to our country’s well-being. Workers are required to file their taxes each year, but the process can be expensive, time-consuming, and complicated. Many taxpayers turn to private companies like Turbo Tax and H&R Block to file their taxes because they aren’t able to access free services within their communities—leading to an average cost of $140 to file taxes. Americans spend an average of 8 hours filing their return.

All of us have surely been left scratching our heads at some point when trying to understand what numbers to use when reporting our income or whether a particular deduction applies to our circumstances. For gig workers and college students, the tax filing process can be especially complex. Tax filers are often scared to file incorrectly and to be penalized—creating even more anxiety in an already complicated process.

For all these reasons, we must have a fully funded and fully staffed IRS with comprehensive customer service available and resources to make tax filing more accessible. But the Trump Administration has threatened to cut up to half of the IRS workforce and to dramatically cut funding for the agency.

When we invest in IRS staff who can help audit wealthy taxpayers, this leads to more revenue for our nation. Unfortunately, these staff are under threat from the Trump Administration. Through the Inflation Reduction Act, lawmakers invested $80 billion in the IRS, and this additional revenue has already had positive benefits. The IRS improved its ability to offer customer service – reducing phone wait times to an average of just over 3 minutes during the 2024 tax filing season. The agency answered about 90 percent of phone calls during the filing season as well. The IRS also used the increased funding to begin improving outdated interfaces and technology and to audit complex, high-income tax filers who evade paying their taxes. As of December 2024, the IRS collected $1.3 billion from very wealthy taxpayers who had not paid their overdue tax debt or filed their tax returns. Importantly, every $1 spent on auditing individuals with high incomes garners an additional $12 in revenue for our nation.

Investments in the Direct File Tool and Taxpayer Assistance Clinics are Vital

The IRS has established the Direct File tool, which provides a free and easy way for people to file their taxes online. In 2024, the program’s first year, 12 states used Direct File and users saved an estimated $5.6 million in tax preparation fees. This year, 25 states have implemented the tool. Lawmakers should invest in the IRS to help make the Direct File tool permanently available. In addition, lawmakers should invest in Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) clinics that help people file their taxes.

Stealing Private Taxpayer Data Will Reduce Trust and Lead to Less Revenue

DOGE is attempting to access private taxpayer data—including from filers with Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs), which are often used by immigrants. This risks the trust and security of Americans and may make people in immigrant communities reluctant to file their taxes, reducing the revenue our nation gets from these taxpayers. The administration has also proposed transferring IRS staff to the Department of Homeland Security where they could assist with deportations. Diverting IRS employees away from their primary functions, such as collecting revenue from the ultra-wealthy who may be evading taxes, to focus instead on deportation would reduce public revenues by billions of dollars annually. This would ultimately reduce efficiency within IRS tax collection systems.

We Must Invest in the IRS, Not Deplete It

Lawmakers should invest in the IRS, not deplete it. Tax filers are better off when our nation invests in resources like the Direct File tool and customer support services. And our economy is better off when lawmakers invest in staff who can audit the wealthiest individuals to raise revenue for public goods and ensure everyone is following the law and paying their fair share. Due to these disruptions in the IRS, the Department of Treasury anticipates a decrease of more than 10 percent—some $500+ billion—in tax receipts in 2025 compared to 2024. The proposed cuts to the agency are part of a larger plan by lawmakers to fund tax breaks for the very wealthiest Americans and corporations at the expense of everyday people.

This statement can be attributed to Cemeré James, interim executive director of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

Washington, D.C., March 28, 2025 – CLASP decries the cuts announced yesterday to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). These reductions will affect mental health, disabled people, rural communities, vaccines for children, and community health workers who address inequities for people across the lifespan, among others.

HHS plays a fundamental role in addressing the well-being of the nation’s 340 million people. Everyone benefits from HHS’s work to fight diseases, promote public health, and provide essential human services. But people with low incomes—especially children and families—have a particular stake in the agency’s work. That’s why CLASP is concerned that HHS is slashing another 10,000 jobs—on top of the 10,000 positions eliminated earlier—as part of Elon Musk’s DOGE project, which has recklessly cut grants and contracts and terminated staff since its inception.

- The proposal eliminates the Administration for Community Living (ACL) by reorganizing it into three different HHS agencies. ACL provides critical programs and services to advance independent living and inclusion for people with disabilities and older adults. This represents just one of many attacks by DOGE on the disability community, which has included detrimental cuts to the Department of Education and the Social Security Administration, among others.

- The HHS reorganization will further undermine the agency’s capacity to process grants, monitor implementation, and provide technical assistance for many programs, including child care and Head Start. The reduction in HHS regional offices from 10 to 5 further challenges this.

- Dismantling the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) will have substantial ripple effects on people’s behavioral health. For example, SAMHSA facilitates the treatment of over 1.5 million people in substance use facilities annually and supports programs that families and communities depend on for mental health support, suicide prevention, and more. Earlier this year, DOGE cut 10 percent of the almost 900 employees at SAMHSA, impacting the provision of critical suicide hotline (988) grants to states, among other key services. SAMHSA also provides significant block grants in community mental health and substance use nationwide. Cutting staff and reorganizing HRSA funding and technical assistance will exacerbate critical gaps in the behavioral health workforce.

Our country is undergoing unprecedented upheaval in programs critical to people who are forced to live on the margins of society during an unpredictable economy poised to get even worse. Drastic cuts like these will only make their lives more challenging. CLASP is committed to joining our partners in resisting these cuts and advocating for alternative approaches that don’t fund tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations by making drastic reductions that harm people with low incomes.