CLASP

The Center for Law and Social Policy

Youth mobile response is a 24/7, police-free crisis intervention service designed to support young people and families in emotional or behavioral crises. Unlike the traditional “mobile crisis” model—which focuses mainly on youth with diagnosed psychiatric conditions—CLASP’s “mobile response” approach emphasizes youth-defined crises and support before, during, and after the critical moment. It is part of a broader crisis care continuum that includes crisis hotlines, stabilization centers, peer services, and short-term crisis residential options.

This publication was produced in collaboration between CLASP and the National Collaborative for Transformative Youth Policy.

>>Download the full report here.

This statement can be attributed to Wendy Chun-Hoon, president and executive director of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

Washington, D.C., August 12, 2025–During a White House press conference on Monday morning, President Trump declared a public safety emergency in Washington, D.C., despite evidence to the contrary. The president federalized the D.C. police department and mobilized 800 members of the National Guard to remove encampments of homeless residents to, in the president’s words, “fight crime” in the city.

The rhetoric used by all speakers at the press conference was racist, xenophobic, transphobic, and discriminatory against homeless members of the D.C. community, who are disproportionately Black. Using othering language like “they/them” referring to youth of color, “bedlam,” or “slums” pathologizes structural inequality. Coupling this language with deliberate misinterpretations of crime data and sensationalized stories places people experiencing homelessness at even higher risk of dehumanization and violence. Under a recent executive order, this population is already facing renewed attacks on strained support systems and privacy protections.

Furthermore, this move by the president is blatant abuse of the D.C. Home Rule Act of 1973 and the latest refusal to grant the District statehood. Trump is flooding the streets with FBI agents and the National Guard and federalizing local law enforcement in spite of violent crime rates that are at a 30-year low in D.C., and in spite of the wishes of D.C. residents, the majority of whom are Black and brown.

Demanding that people experiencing homelessness leave the city will not make D.C. safer. In fact, the resources diverted toward mass displacement of homeless people will result in a greater police presence. The root causes of homelessness include unaffordable rents, lack of access to mental health and substance use treatment, and unlivable wages. To truly end homelessness, we should invest public dollars in expanding the supply of affordable housing and ensuring accessible, high-quality mental health and substance use treatment services.

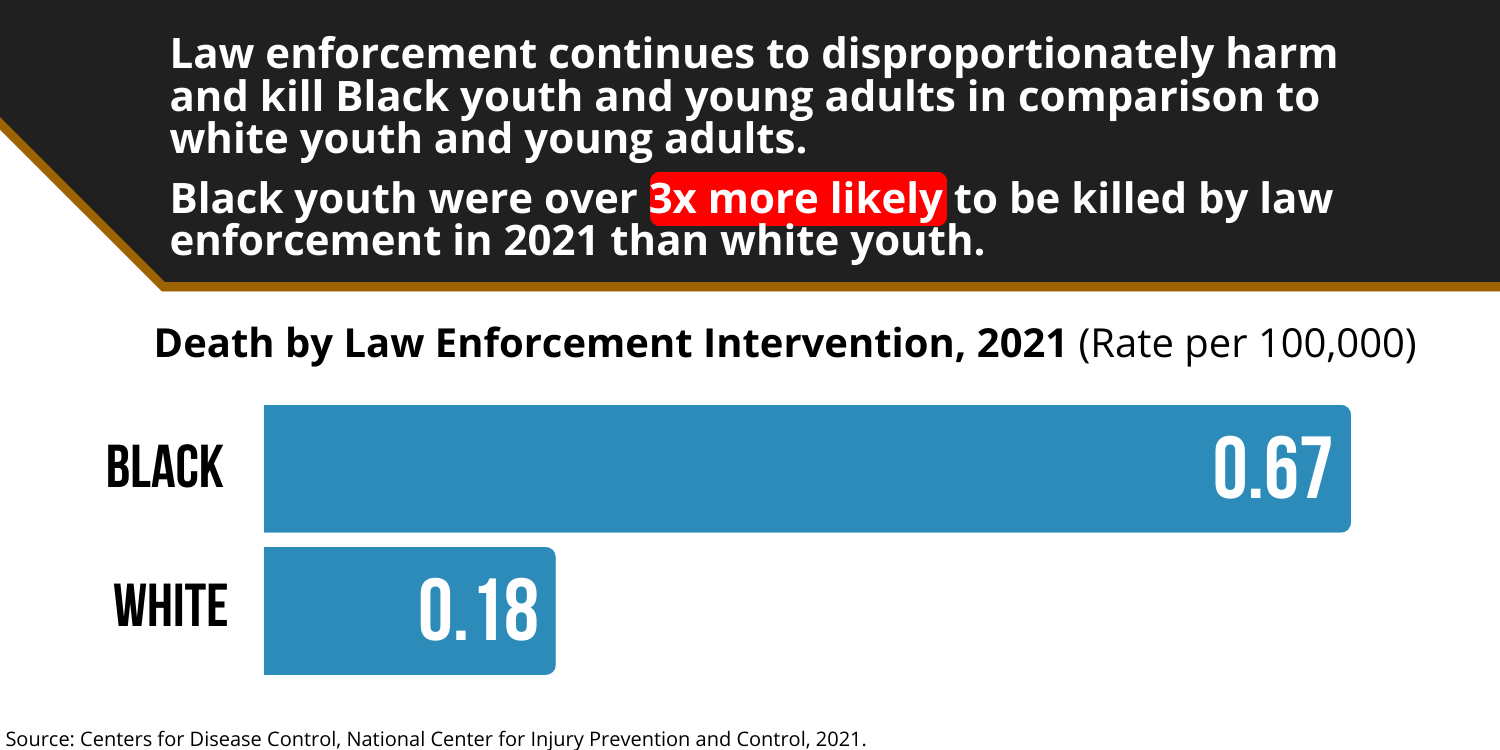

Additionally, researchers have repeatedly disproven a direct link between more law enforcement agents and a higher level of public safety, invalidating measures aimed at “restoring law and order,” which ultimately hurt Black and brown people disproportionately. This increased presence can have deadly consequences, as it did in Milwaukee when a local Black man was killed by out-of-town law enforcement brought in to securitize the downtown area for the Republican National Convention.

In addition to the inappropriate takeover of the D.C. police department, Trump’s deployment of the National Guard to strike fear into the local population mirrors how the administration used the deployment of 4,000 guard troops and 700 active Marines in Los Angeles to facilitate the arrest and deportation of immigrants and quell people’s constitutionally protected right to non-violently protest their neighbors’ kidnapping.

Like L.A., D.C. is being used as a testing site to normalize the use of military personnel against people in our community without the existence of an actual crisis. Rather than advance public safety, the administration’s actions further a political agenda rooted in demonizing race and poverty.

At a time when people with the lowest incomes are already struggling with inflation, a softening job market, and the slashing of programs that support basic needs, the last thing our nation should do is to use force against people who don’t have the resources to fight back.

By Kaelin Rapport

Last month, California relied on incarcerated firefighters to prevent and put out fires that ravaged vast swaths of Los Angeles County. The practice of using incarcerated individuals as forced labor has existed for decades and is part of an exploitative prison labor economy that balances state budgets at the cost of Black lives.

Involuntary Servitude and Punishment

Carceral firefighting practices can be traced to slavery, as the use of Black labor was integral to fire management strategy, setting a violent precedent of placing the “inferior” on the frontlines of danger. California began using prisons as a source of enslaved labor for public works in the late 19th century when, as now, disproportionately warehoused Black people. Today, Black people account for 5 percent of the state population and yet comprise 28 percent of the state’s prison population.

That this exploitation persists is due in part to a loophole in the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime” by removing the constitutional provision allowing jails and prisons to punish those who refuse to work. Last November, California voters failed to pass Proposition 6, which would have closed that loophole. The proposition’s failure was partially due to persistent claims that contemporary work programs like the Conservation (Fire) Camp are voluntary.

Today, approximately 70 percent of incarcerated individuals are assigned to work, and the overwhelming majority reported feeling forced into jobs like fighting fires. Incarcerated Black laborers are more likely to either receive no pay for their labor or work in positions with lower pay than their white counterparts. This placement can be arbitrary or used as a form of punishment. Incarcerated individuals who refuse face the threat of accruing sanctions, being deprived of the few opportunities available to see family and/or reducing their sentences.

Roughly 30 percent of the crews that combat California’s wildfires consist of incarcerated laborers, which amounts to over 1,000 incarcerated firefighters. Some are as young as 18 – the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) launched youth programs at the Growlersburg and Pinegrove Conservation Camps in 2023 and 2024.

The Costs of Cost-Saving

Programs like the Conservation Camps have received praise for allowing states to save hundreds of millions of dollars by using prison labor to fight fires and provide training for post-incarceration employment. Incarcerated laborers produce over $2 billion in goods and $9 billion in services in the upkeep of carceral facilities. However, this arrangement obfuscates the social costs of mass incarceration while perpetuating racial inequities and damaging local economies.

State law allows the CDCR to pay half California’s minimum wage of $16/hour. For the highly dangerous and arduous work of clearing areas around wildfires to prevent their spread, incarcerated firefighters receive anywhere between $5.80 and $10.24 a day; an additional $1/hour when responding to emergencies; and two days off their sentence for each day spent fighting fires. These meager wages frequently go toward meeting basic hygienic needs, making phone calls, and buying additional food from the prison commissary.

Because of their criminalized status, incarcerated laborers are excluded from federal protections under the Fair Labor Standards Act, the National Labor Relations, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. They are also unable to unionize. It is also essential to keep in mind that, in addition to lacking adequate compensation, incarcerated laborers are often fighting wildfires without appropriate medical care or protective equipment.

As a result, the harm these laborers face from abysmal conditions inside prisons is mirrored in their life-saving work on the outside. Incarcerated firefighters are four times more likely to be physically injured on the job, eight times more likely to sustain an injury from smoke inhalation than professional firefighters, and largely unable to continue this work after being released. California law bars many with criminal convictions from receiving certification as emergency medical technicians (EMTs), a requirement to become a firefighter in the state.

Looking Forward

California is among the 14 states maintaining fire camps that sacrifice incarcerated Black laborers for a public that has historically required their exclusion and exploitation. Being overpoliced, disparately incarcerated, and forced to work for minimal or no pay makes neither Black communities nor anyone else safer.

The following measures would make necessary strides in de-escalating the systemic violence of coercion Black incarcerated laborers suffer via California’s carceral system and serve as a model for other states to follow:

- Abolishing sanctions for refusing to work as an institutional practice. Incarcerated individuals’ agency should be respected, and their humanity valued beyond their capacity to generate capitalist value.

- Incarcerated firefighters must be paid the local minimum wage. The need for their labor based on geographic location and unique climate conditions should be accounted for, in addition to exposure to lasting bodily harm.

- Offering incarcerated firefighters the same medical and disability benefits as all firefighters for incurring an injury while working.

- Striking down restrictions that bar individuals with a criminal conviction from gaining certification as an EMT. This exclusion remains a significant barrier to employment post-release while allowing the Los Angeles Fire Department to maintain a neutral position on the topic.

(EXCERPT)

‘New Jim Code’: Federal officials have failed to deter the civil rights harms that artificial intelligence in schools poses to students of color, a new report argues. | The Center for Law and Social Policy

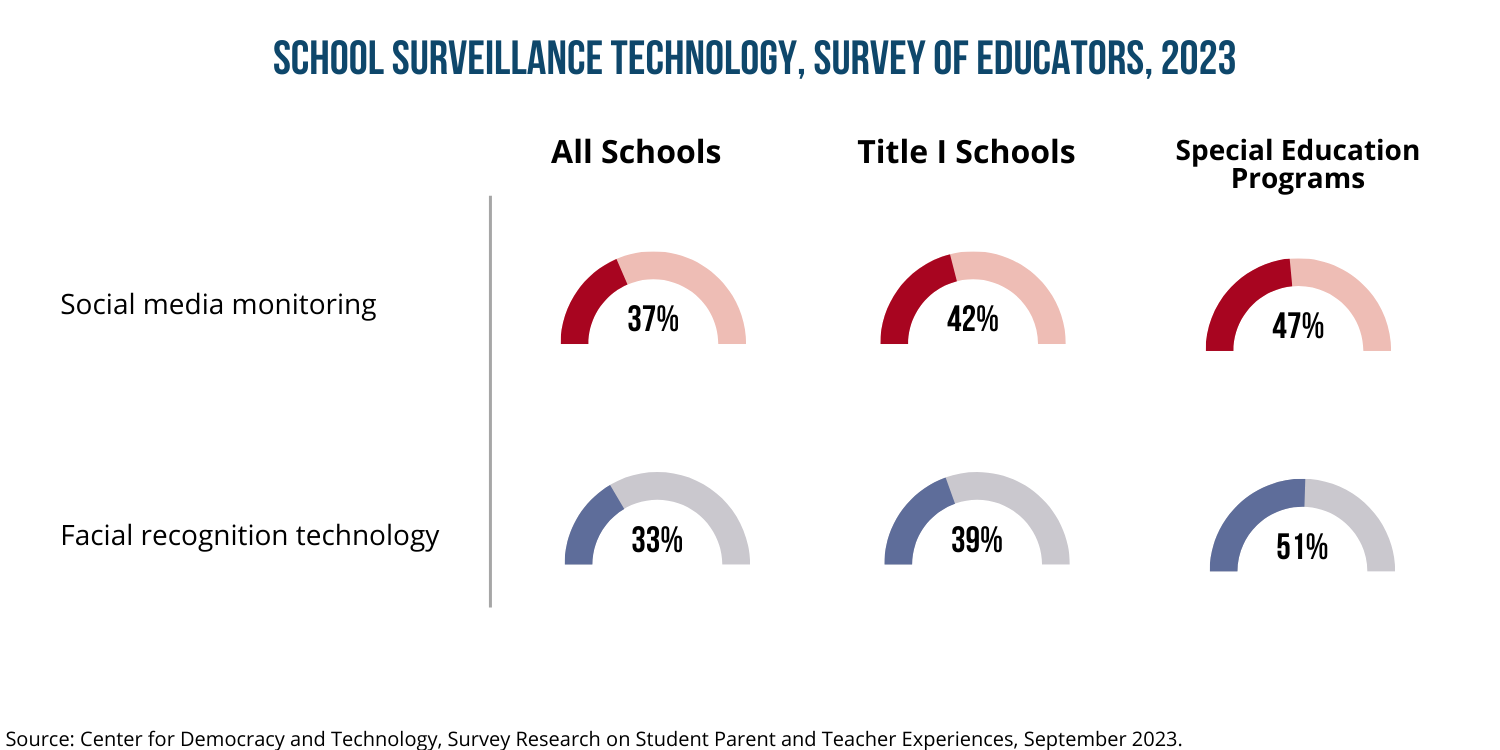

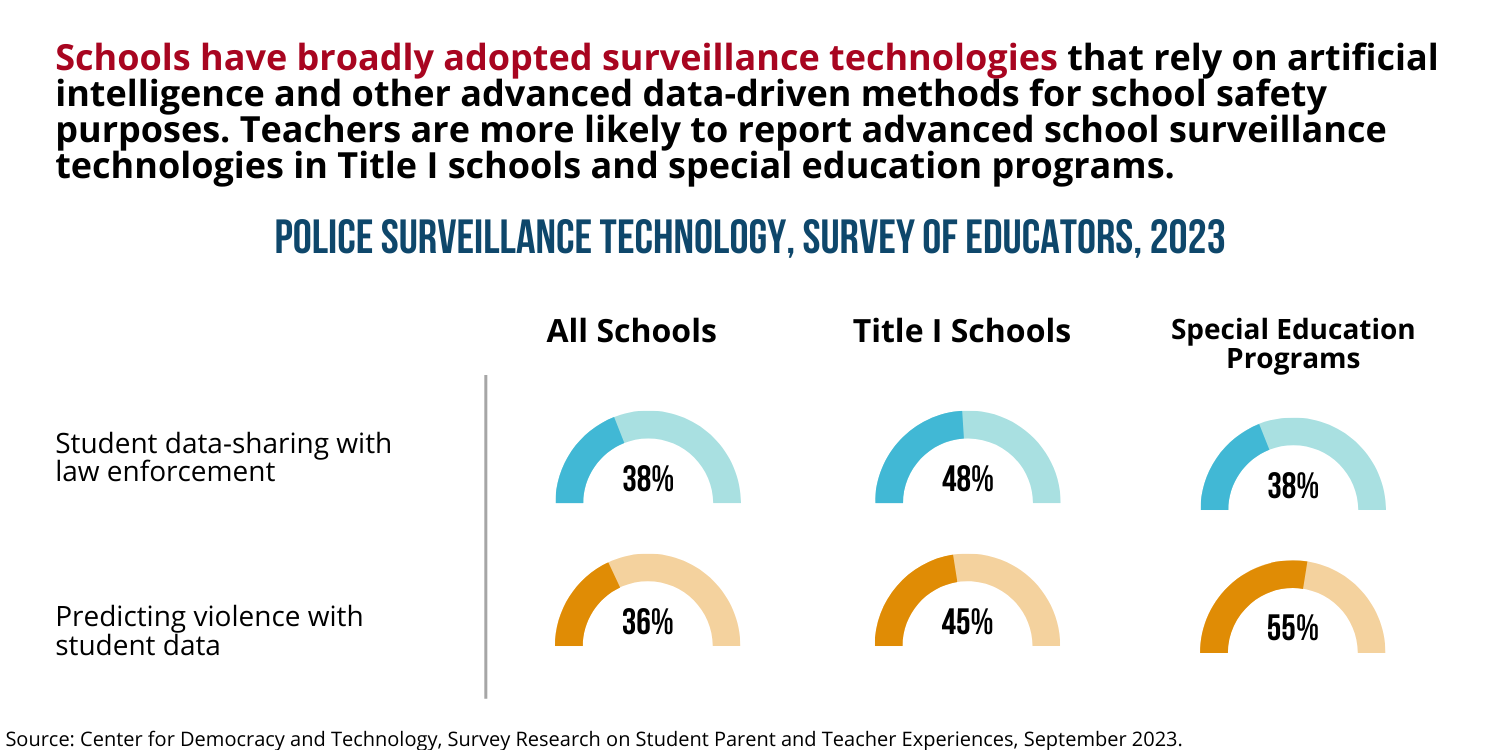

Public and private actors are turning to artificial intelligence (AI) and other big data technologies to engineer new futures for structural racism and social inequality in the United States, a phenomenon that the sociologist Ruha Benjamin has termed the “New Jim Code.”

These technologies are upending decades of civil and human rights legal standards, expanding mass criminalization, restricting access to social services, and enabling systemic discrimination in housing, employment, and health care, among other areas.3 The New Jim Code carries unique threats to youth and young adults of color, especially in the context of K-12 public schools.

In recent years, federal policymakers have taken steps to address the societal implications of AI and big data technologies, including the White House Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights, President Biden’s Executive Order on Artificial Intelligence, and the U.S. Department of Education’s guidance on AI in schools. However, these efforts have largely failed to address the specific harms that these technologies raise for youth and young adults of color and youth from other historically marginalized communities.

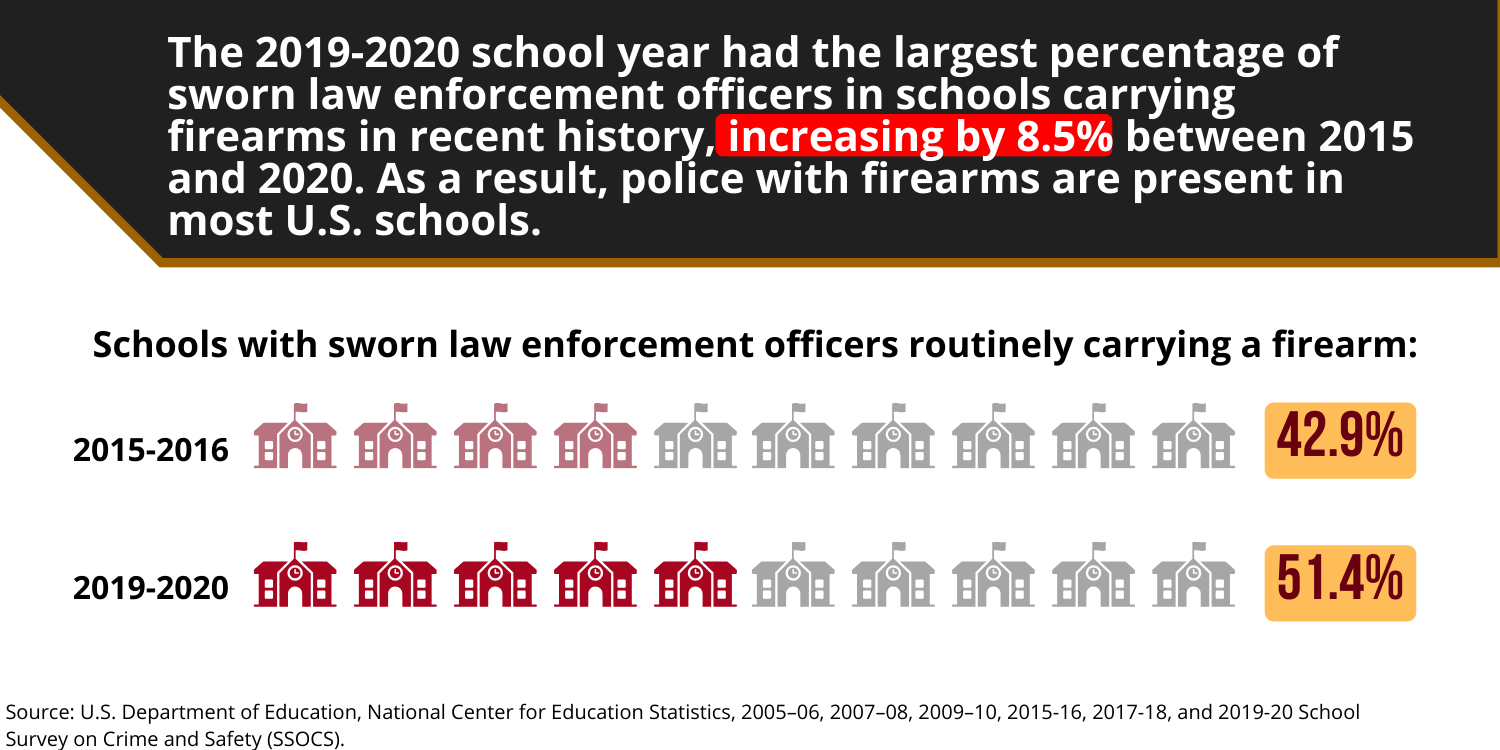

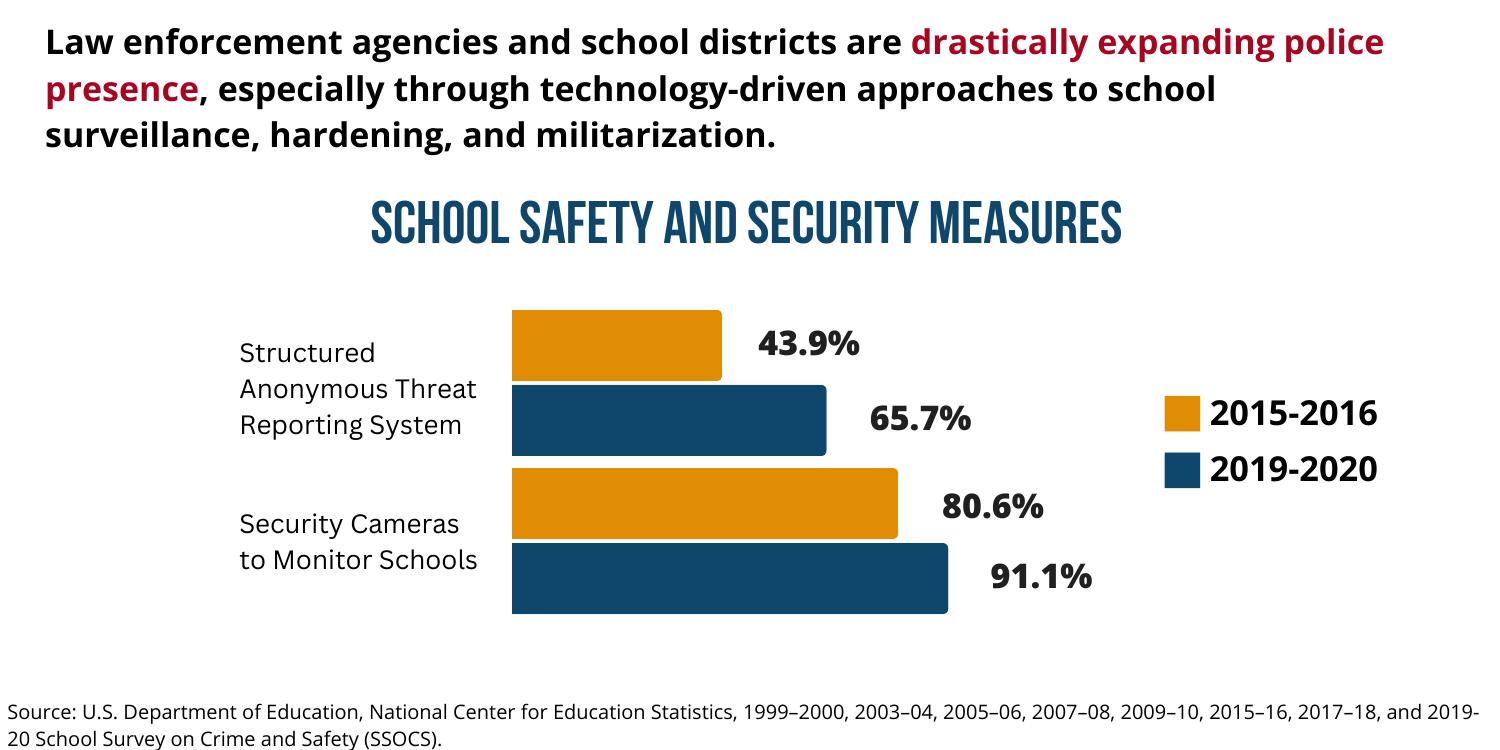

As the infrastructure of police surveillance grows in public schools, communities must be prepared to safeguard the rights and freedoms of students and families. This report is designed to help youth justice advocates, youth leaders, educators, caregivers, and policymakers understand and challenge the impact of school surveillance, data criminalization, and police surveillance technologies in schools.

- This report includes:

- An analysis of six key facts about the impacts of data criminalization and school surveillance technologies on education equity.

- A case study of an AI school surveillance technology that can land children in adult misdemeanor court.

- Key recommendations for education policymakers and school district leaders for advancing youth data justice.

By Lulit Shewan

An exploitative labor economy exists within the confines of this nation’s prisons. This is a fundamental pillar of the criminal justice system, yet it is largely concealed from public view. In the United States, all state and federal prisons allow some form of involuntary labor as part of various correctional work programs. Even when prison labor is ostensibly voluntary, the combination of meager pay (often less than $1/hour) and the presence of harsh alternatives creates an inherently exploitative system that depends on the labor of those behind bars and perpetuates a cycle of exploitation and marginalization. Prison labor amplifies deep-seated issues within the criminal justice system and casts a stark light on the intersection of labor rights, social justice, and the ethics of incarceration

The Exploitative Prison Labor Economy

Incarcerated men and women toil in workshops, kitchens, and fields, producing goods and services that reach far beyond their confinement. From manufacturing furniture and processing food to fighting fires and working in call centers, their labor fuels supply chains, corporate profits, and consumer markets. Yet these workers remain invisible, their contributions often overlooked or dismissed. The commodification of their labor perpetuates a cycle of vulnerability, where meager wages and limited rights prevail. In the intricate tapestry of the prison industrial complex, we confront a profound challenge that transcends temporary reforms. The only holistic and ethical approach calls for a paradigm shift, a reimagining of justice itself. Within this context, we fiercely advocate for granting incarcerated individuals fundamental rights: the right to choose voluntary work and earn fair wages, and the freedom to join unions. These rights are not concessions; they are affirmations of human dignity and agency, and are necessary to improving the

material conditions of incarcerated people.

By Jesse Fairbanks

In late April, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in an important case regarding homelessness. Grants Pass v. Johnson will decide whether the city of Grants Pass, Oregon, violated the constitutional rights of people experiencing homelessness by fining or arresting them for sleeping outdoors—even when there were no shelters to take them in.

At the same time, several states and municipalities have expanded involuntary treatment at residential facilities for people struggling with mental illness or substance use. Most of these expansions target people experiencing homelessness who have crises in public. By one estimate, one-third of people who are homeless have a serious mental illness and one in five struggle with substance use. As a traumatic life event, homelessness can cause or exacerbate symptoms of mental illness and addiction.

In March, California voters narrowly passed Proposition 1, a sweeping measure pushed by Governor Gavin Newsom that will add new treatment beds in residential facilities. The state recently broadened the scope of its conservatorship law to include those who can’t provide for their basic needs, resembling a similar measure championed by Mayor Eric Adams in New York City. Other states like Oregon are considering similar expansions.

Although policymakers argue that involuntary treatment can help people experiencing homelessness, expanding forced treatment will have the same consequences as the Supreme Court siding with Grants Pass. Both interventions seek to hide people experiencing homelessness from public view; both seek to make unsheltered homelessness less visible rather than end it.

[…]

>>Read the full op-ed on The Progressive

By Clarence Okoh

Testimony about his extensive experience in combating the use of emerging technologies to undermine the civil and human rights of youth and young adults of color. He highlighted his involvement in initiatives such as the PASCO Coalition: People Against the Surveillance of Children and Overpolicing, which successfully challenged predictive policing programs in schools, resulting in policy changes and federal investigations. Okoh also co-founded the NOTICE Coalition: No Tech Criminalization in Education, advocating to end the use of data and technology for surveillance and criminalization in education. He emphasized the importance of translating the radical imaginations of youth of color into legal and policy solutions.

In his testimony, Okoh focused on the alarming rise of AI-enabled police surveillance technologies in public schools, urging policymakers to implement bans and comprehensive data privacy protections to safeguard the rights of marginalized youth.

By Deanie Anyangwe

4 min read.

“[M]urder rate go up—murder rate go down—like I said. But there’s always killing.”

-Young Adult Focus Group Participant, Behind the Asterisk*, 2019

For many young people in the United States, community violence is an unfortunate part of daily life. Also called neighborhood violence, community violence is an interpersonal form of violence between individuals not involved in familial or intimate relationships. It includes incidents such as shootings, stabbings, and other aggravated assaults; is often carried out by young people; and frequently occurs in public settings. These situations happen when complex environmental factors like poverty, structural racism, systemic disinvestment, and easy access to alcohol, drugs, and weapons coincide.

“I was stabbed six times with a screwdriver, and the second time I was stabbed six times in the night. So that makes me who I am now. I never trust anybody to be behind me. I always watch my back.”

-Young Adult Focus Group Participant, Behind the Asterisk*, 2019

Community violence is a traumatic stressor that has damaging effects on young people’s mental, social, psychological, physical and economic well-being. Young people exposed to violence are at risk for poor long-term behavioral and mental health outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, and aggressive behaviors. In instances where young people are chronically exposed to community violence, they may also demonstrate symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, regardless of whether they are victims, direct witnesses, or hear about the crime. Evidence also shows that people who were exposed to gun violence fatalities experienced higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation than those who were not exposed.

Community violence also creates barriers to developing healthy relationships with peers and community members. Young people are less likely to use public spaces such as parks due to safety concerns. Youth exposure to community violence is associated with poor academic performance, educational outcomes, labor force participation, and earnings into adulthood. Exposure to community violence and the ripple effects of trauma and grief place enormous strain on children and youth, families, schools, employers, hospitals, government systems, and entire communities.

Gun violence overwhelmingly harms people in communities that have been economically marginalized. Neighborhoods with high levels of violence routinely face multiple compounding challenges arising from and exacerbated by structural inequity and racist policies such as segregation; limited availability of or access to quality jobs; a lack of safe and affordable housing; a lack of affordable, quality physical and mental health services; and histories of divestment. Moreover, significant research on the interactions of place and violence, along with a robust body of evidence, demonstrates the connection between state-sponsored racial segregation and rates of violence today.

“But, you know, and then on the other hand, you have these communities where people feel that we need to shoot each other, you know? You got gangs being the only support that people have. You got all these bad and bad influences, mental health problems, mass shootings. You don’t know. People are, they’re not getting support like on all fronts.”

-Young Adult Focus Group Participant, 2023

While some young people embrace guns, this is largely due to a collective failure to keep our young people safe using non-carceral, community-centered, effective community safety strategies. Many young people that carry guns don’t intend to commit crimes but feel the weapons are necessary to protect their own physical safety. They often have guns to protect their own physical safety and largely do not convey any intent to use these weapons to proactively commit crimes.

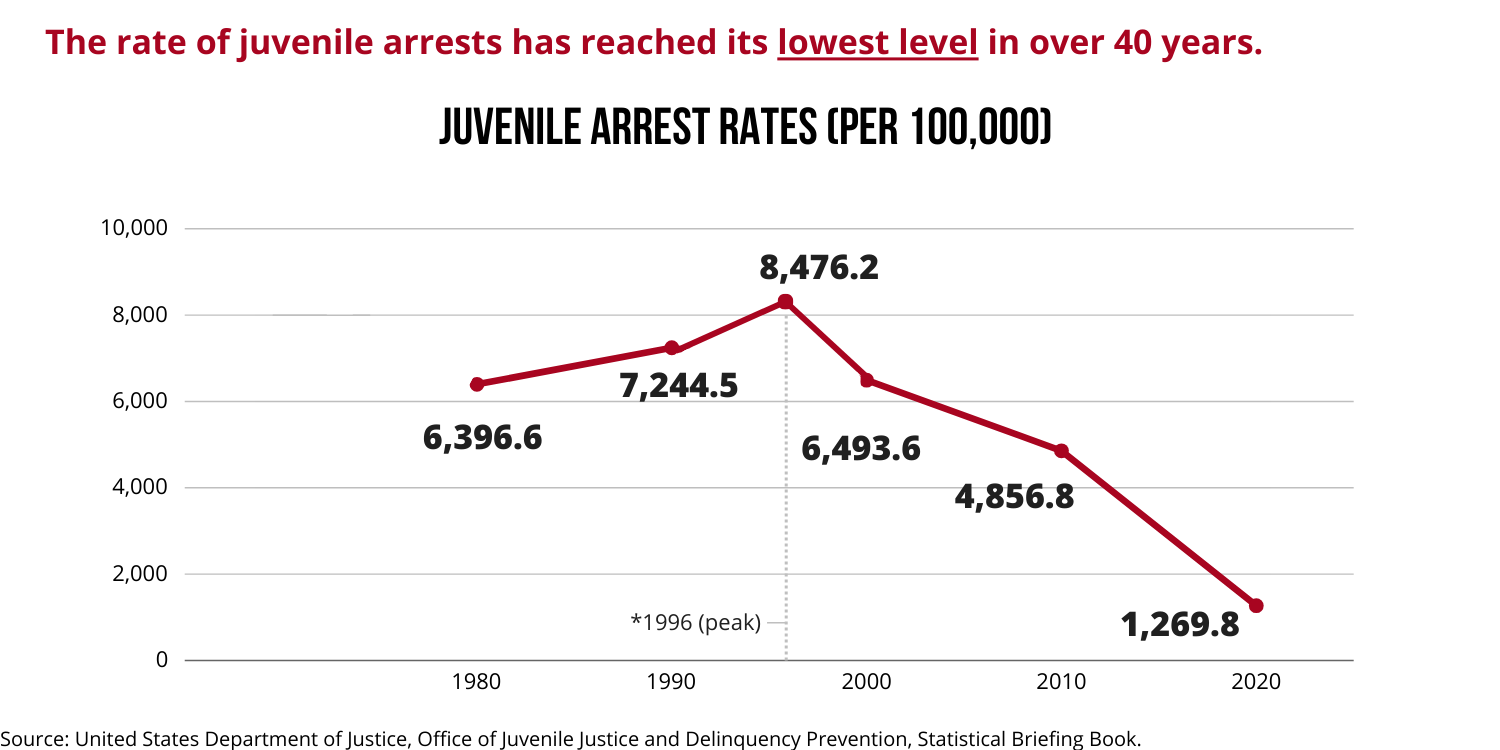

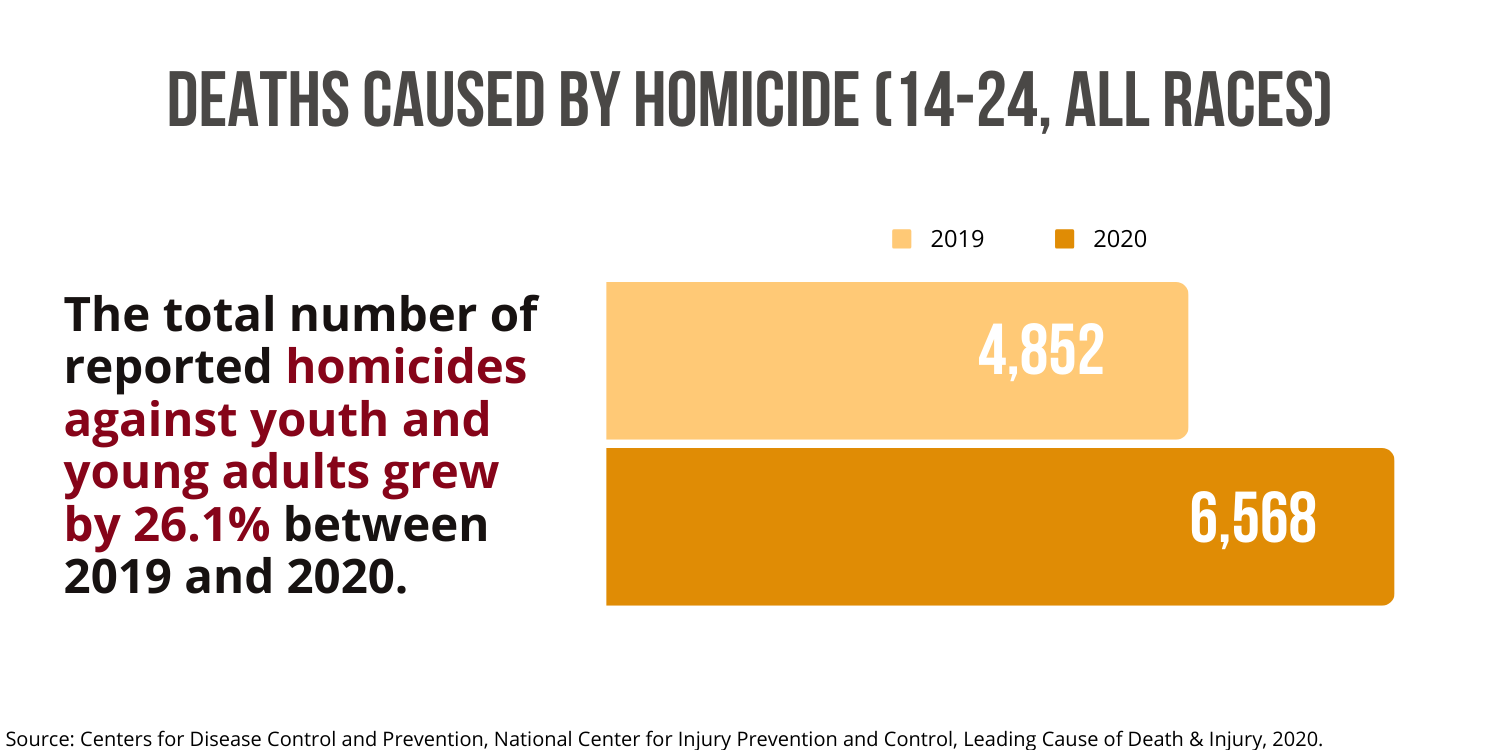

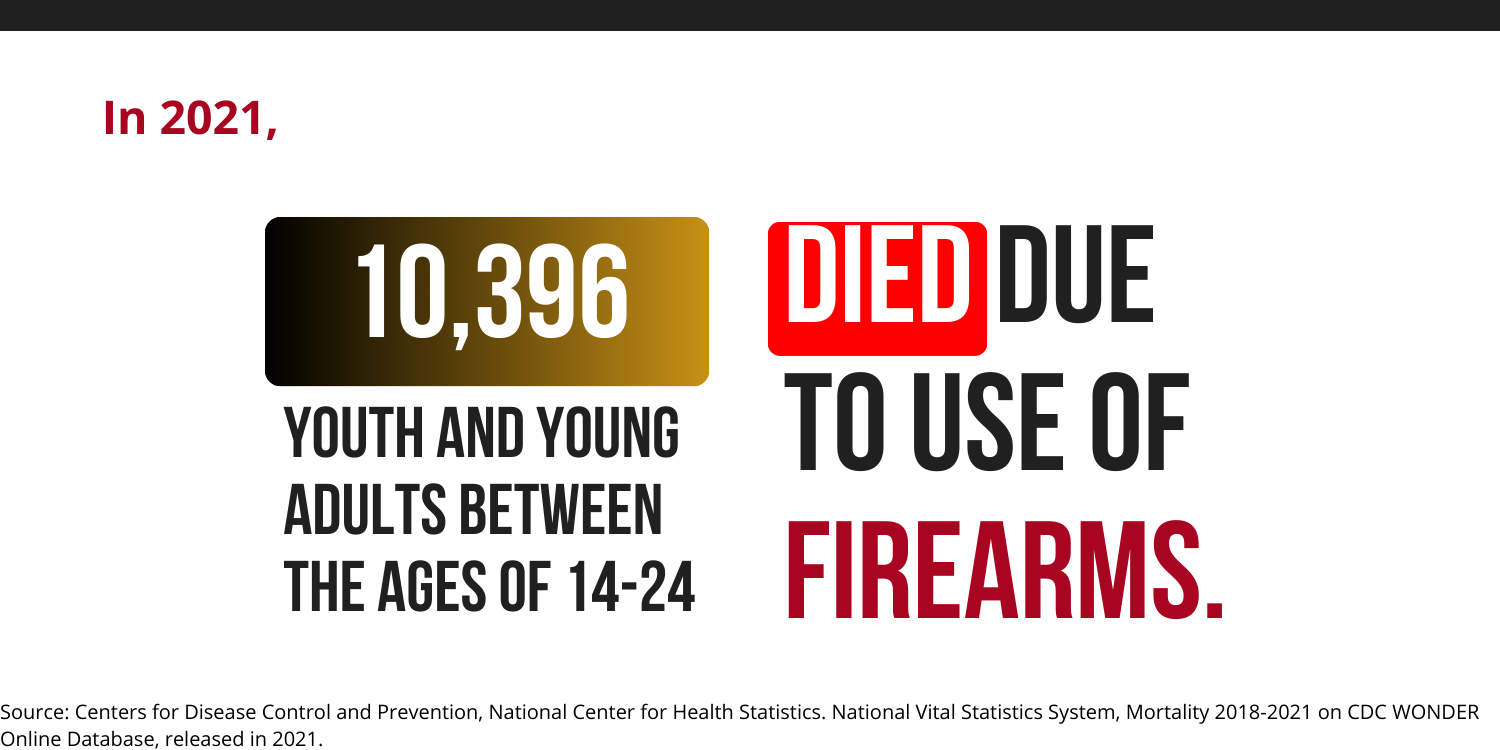

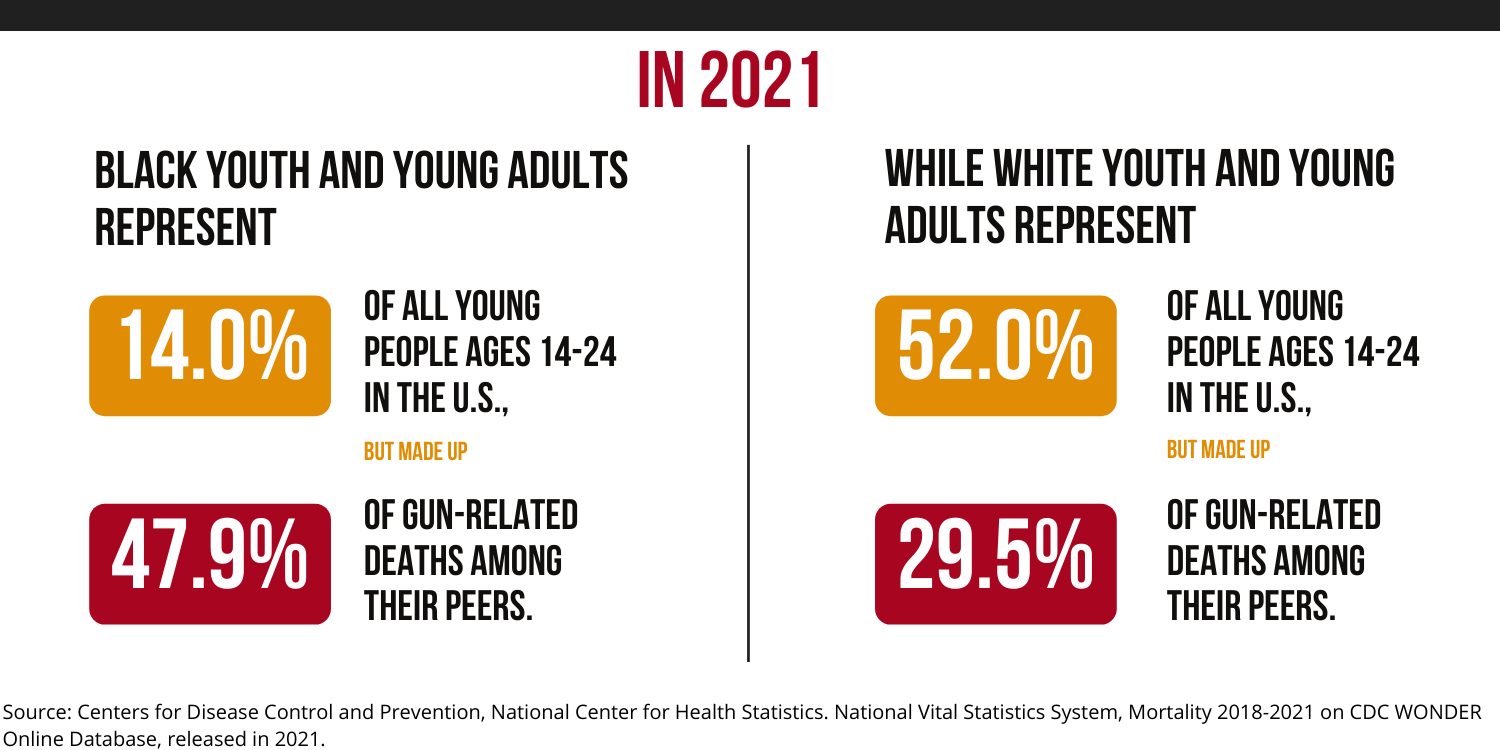

Black youth are 14 percent of young people ages 14-24 in the U.S., but account for nearly 48 percent of all gun-related deaths among all young people in this age group. Yet Black youth continue to be targeted as the cause for the rising violence in America. Policymakers in states such as Maryland and Georgia and cities including Washington, D.C., New York City, and Philadelphia are pathologizing Black youth to justify anti-Black, tough on crime policies, despite the vast evidence that these policies are both destructive and ineffective. This bipartisan effort to criminalize Black youth subjects them to state-sanctioned violence as punishment for structural problems that they did not create. And while the overall number of homicides committed by youth rose slightly in recent years along with national trends, current youth arrest rates are the lowest that they have been in the last 40 years.

Successful non-carceral CVI strategies that have led to decreases in community violence in cities across the country include non-police street outreach and violence interruption, and hospital-based violence intervention programs. Policymakers examine these strategies, and embrace a structural analysis to understand the reasons that cause young people to own guns, and invest in communities to enable them to lead this work. Policymakers must adopt a more nuanced understanding of the roles systemic divestment, place-based disadvantage, anti-Black racism, racial capitalism, mass criminalization and other critical factors have in driving community violence. Lastly, policymakers should ground proposed interventions in knowledge of how interlocking systems of violence manifest to create the circumstances that lead to community violence in order to effectively address the problem and keep our young people safe.

Behind every act of community violence there are families, friends, and communities left to grapple with the aftermath of trauma, injury, and/or loss of life. Interventions that address community violence support youth mental health. Our young people have been clear on what they need. It is now on us to do our part to keep them safe.

>>Return to full Youth Data Portrait

>> Learn more about the New Deal for Youth