The “Great Equalizer”: Women in Higher Education

By Asha Banerjee and Rosa García

March marks Women’s History Month. As we honor the contributions of women in our lives, we’re reflecting on women’s strides in higher education, the challenges ahead, and policy solutions to continue key progress.

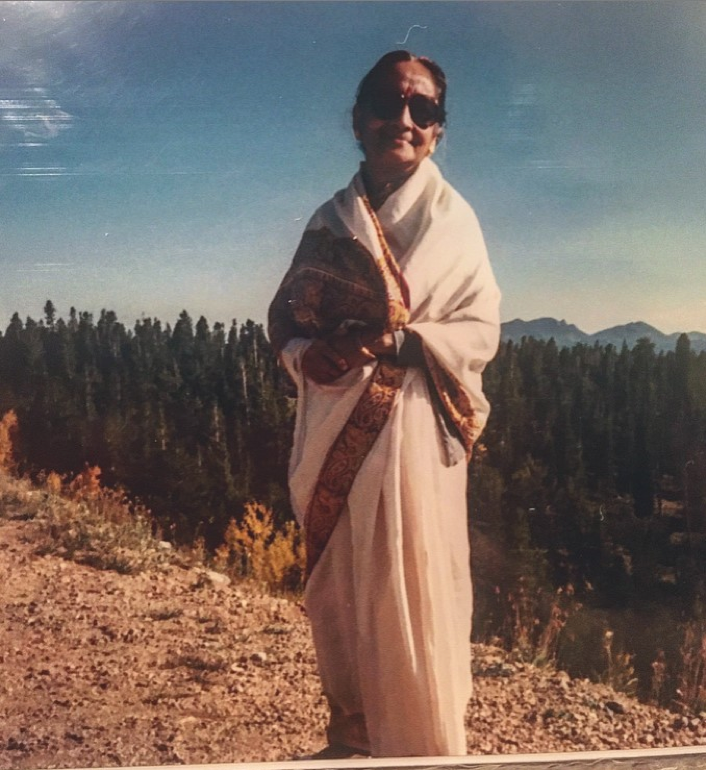

Asha: My grandmother came of age in the last days of British rule in India. In a patriarchal and colonial society, she not only attained a bachelor’s degree, but also won a Fulbright scholarship to Teacher’s College, Columbia University in 1952. Sadly, further higher education became a road not taken. She had to turn down the scholarship to marry. When I attended Columbia 61 years later, I was able to take the road she could not. My grandmother taught me about resistance and racial and economic justice. She taught me to reach upwards and to fight to ensure that others had access to high-quality postsecondary education.

Joya

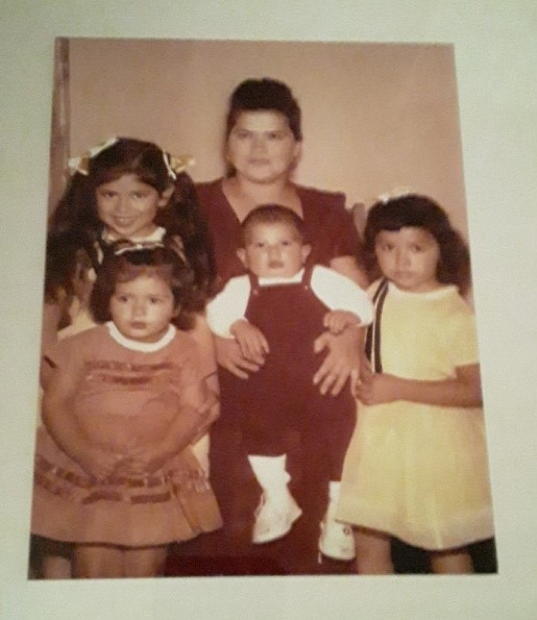

Rosa: For my mother, an immigrant from México, a college degree was “the great equalizer,” the pathway out of poverty. Because she was unable to access educational opportunities, she worked nights in a cannery in Los Angeles and took care of children to help provide for our family. She ensured that her children got a good education. My sisters and I earned bachelor’s degrees; some earned graduate degrees. In 2015, I was the first in my family to earn a doctorate. Today, I honor my mother and godmother—strong, compassionate women who encouraged me to have big dreams, the courage to imagine a more prosperous life for myself and others, and to have an unwavering commitment to social, economic, and racial justice.

María Teresa

Women, and women of color, have made remarkable gains. Civil rights laws adopted in the 1960s and 70s, investments in federal student aid, and affirmative action policies have helped many students of color access higher education. In 2019, women held more than half (57 percent) of all bachelor’s degrees. Further, a higher percentage of women had bachelor’s degrees than men in every racial category, except Asian Americans.[i] Considering that many colleges and universities refused to admit women as late as the 1980s, we must celebrate the increased representation of women in higher education.

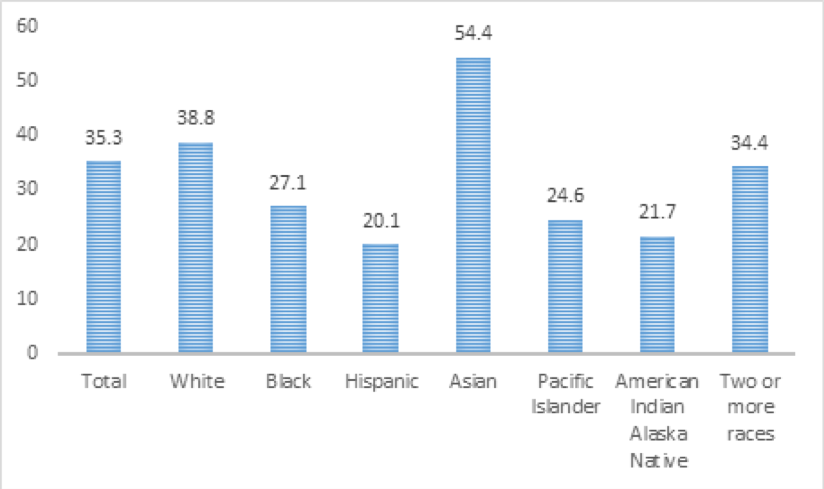

Despite progress, women of color continue to face barriers in postsecondary education compared to women as a whole. Inequalities persist, driven by lack of generational wealth, structural discriminatory federal policies, and other forces. Bachelor’s degree attainment for Black, Latinx, Native American, and Pacific Islander women still lags far behind the national average.

Figure 1: Female Bachelor Degree Attainment (%), 2018

Source: National Center for Education Statistics, Table 104.10

Though more women than men earn their degree, they also carry the vast majority of student debt. A 2017 report found that women owed nearly two-thirds of all outstanding U.S. student debt, about $929 billion. In 2019, women held $21,619 in debt, almost $3,000 higher than men. This debt becomes heavier considering the rise in tuition, housing, child care, and other basic living expenses. The debt burden and disparity are starker through a racial lens: in 2019, Black women owed $30,366, more student debt than women overall.

Women of color bear the brunt of an unaffordable higher education system, which also perpetuates wealth inequality for them and their families. With higher debt and long repayment schedules, women often postpone buying homes, investing in retirement, starting families, or saving. Skyrocketing college costs bury women in debt, keeping them from building wealth and living healthy, prosperous lives. This burden is especially higher for first-generation students of color.

Women are also penalized with the gender pay gap. According to the National Women’s Law Center, Black women only make 62 cents for every dollar paid to their white male peers. For Latinas, the figure is even lower, at 54 cents. Unsurprisingly, with less disposable income, women take about two years longer than men to repay loans. This figure is likely higher for Black and Latinx women, who report additional financial difficulties while repaying student loans.

To truly ensure that higher education offers diverse women equitable opportunities to thrive, lawmakers have to address these crushing costs, which they can do in a variety of ways. Congress must:

- Double the maximum federal Pell grant award, which is currently $6,195, and restore incarcerated students’ ability to access this aid

- Offer students debt-free college

- Triple funding for the Child Care Access Means Parents in School (CCAMPIS), a program which subsidizes campus-based childcare services to student parents with low incomes

- Strengthen Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants (SEOG), which are reserved for college students with the greatest financial aid need

- Allow undocumented students to access federal student aid

- Cancel student loan debt for most borrowers

- Strengthen the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program

- Increase targeted investments in Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Minority-Serving Institutions, and community colleges

Advancing these policy changes would allow women with low incomes and women of color to graduate debt-free and with the economic security they deserve.

While we celebrate more women in higher education and in a variety of fields and disciplines, we can’t forget the pay inequities that women continue to face. We can’t ignore the insurmountable burden of debt confronting millions of women, especially women of color. The fight for economic and racial justice continues.

[1] Disaggregated from overall Asian American and Native American Pacific Islanders.