Economic Recovery Must Center Black Workers

By Asha Banerjee

Black workers are, and have always been, essential to the economy and to our country. This year we celebrate Black History Month amid a set of unparalleled crises: the continuing COVID-19 public health emergency and a deepening economic recession. Both have undeniably had an outsize impact on Black workers. Due to a mix of systemic racism and ingrained, structural inequities, Black workers are overrepresented in high-risk, low-wage industries and have disproportionately less access to adequate medical and financial supports. As Congress moves forward on an urgent COVID relief package and looks ahead to broader economic recovery policies, history can teach us how to create a just and inclusive economic recovery for those who have contributed, and lost, the most.

Perhaps the clearest line from past to present is how policymakers have continually failed Black workers in economic recovery plans. Without deliberate, strategic policies to uplift Black workers now, we risk repeating history. In 1934, in the depths of the Great Depression, W.E.B. DuBois described how Black workers had fared economically:

The World War and its wild aftermath seemed for a moment to open a new door; two million black workers rushed North to work… They met first the closed trade union which excluded them from the best paid jobs and pushed them into the low-wage gutter…Then they met the depression. Since 1929 Negro workers, like white workers, have lost their jobs, have had mortgages foreclosed on their farms and homes, have used up their small savings. But, in the case of the Negro worker, everything has been worse in larger or smaller degree; the loss has been greater and more permanent.

DuBois described how systemic discrimination denied Black workers opportunity and financial security. Unfortunately, his words ring as true today as they did nearly 90 years ago. In periods of growth, the economic picture for Black workers looks very different, whether in the 1920s DuBois refers to, or in the lead-up to the COVID-19 crisis, when policymakers celebrated an overall 3 percent unemployment rate. And in recessions, Black workers suffer even worse and already existing disparities widen.

There is a pattern of excluding Black workers from landmark legislation: Both the Social Security Act of 1935, which established old age benefits for workers, unemployment compensation, workplace accident compensation and more, and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which established a minimum wage and overtime pay, excluded agricultural and domestic workers, which were sectors with largely Black workers. In the more recent past, the austerity policies carried out after the 2008 crisis also disproportionately harmed Black workers. Black-owned businesses were also among the very last to receive critical funding to support their employees from the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) in the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.

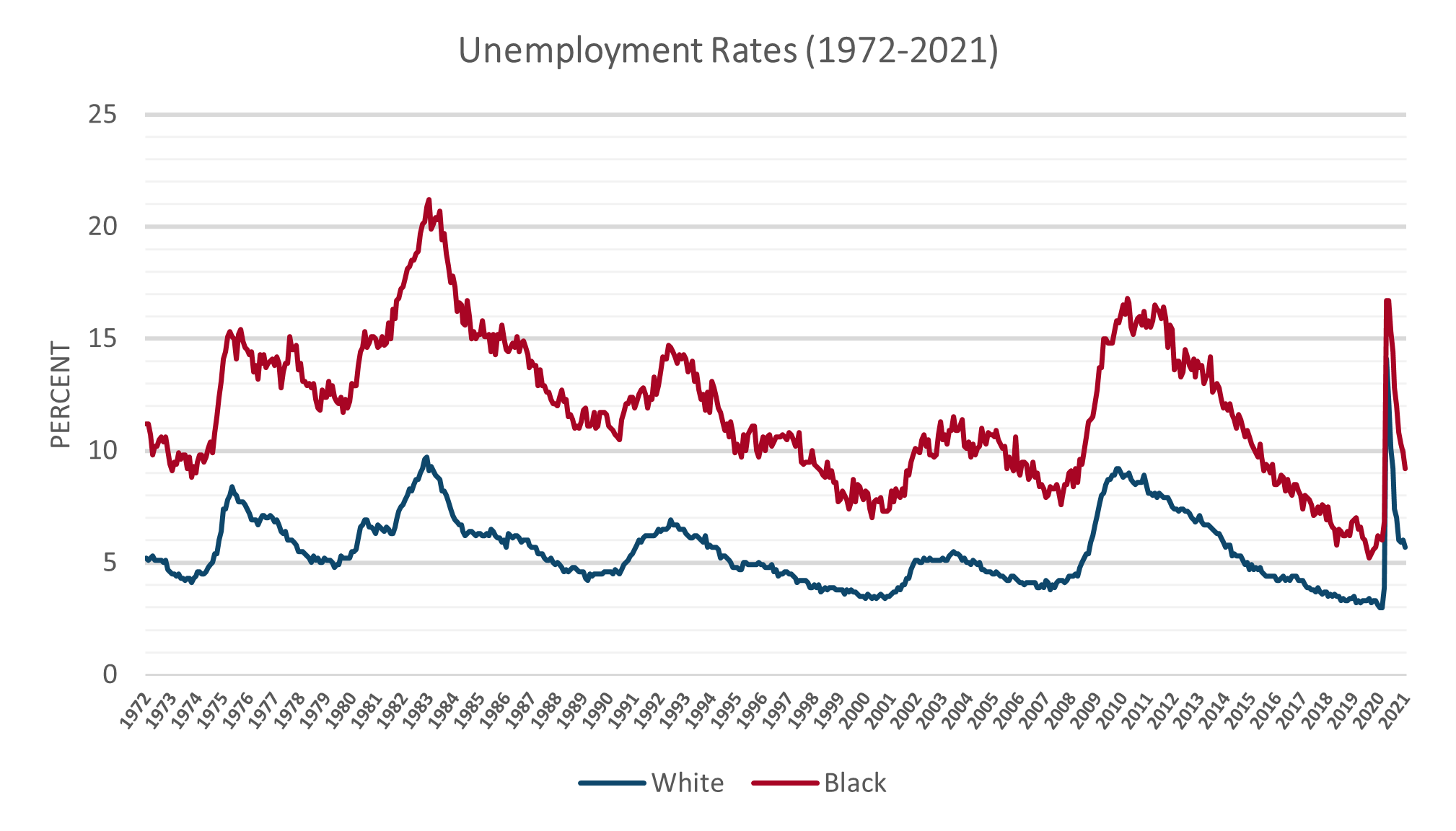

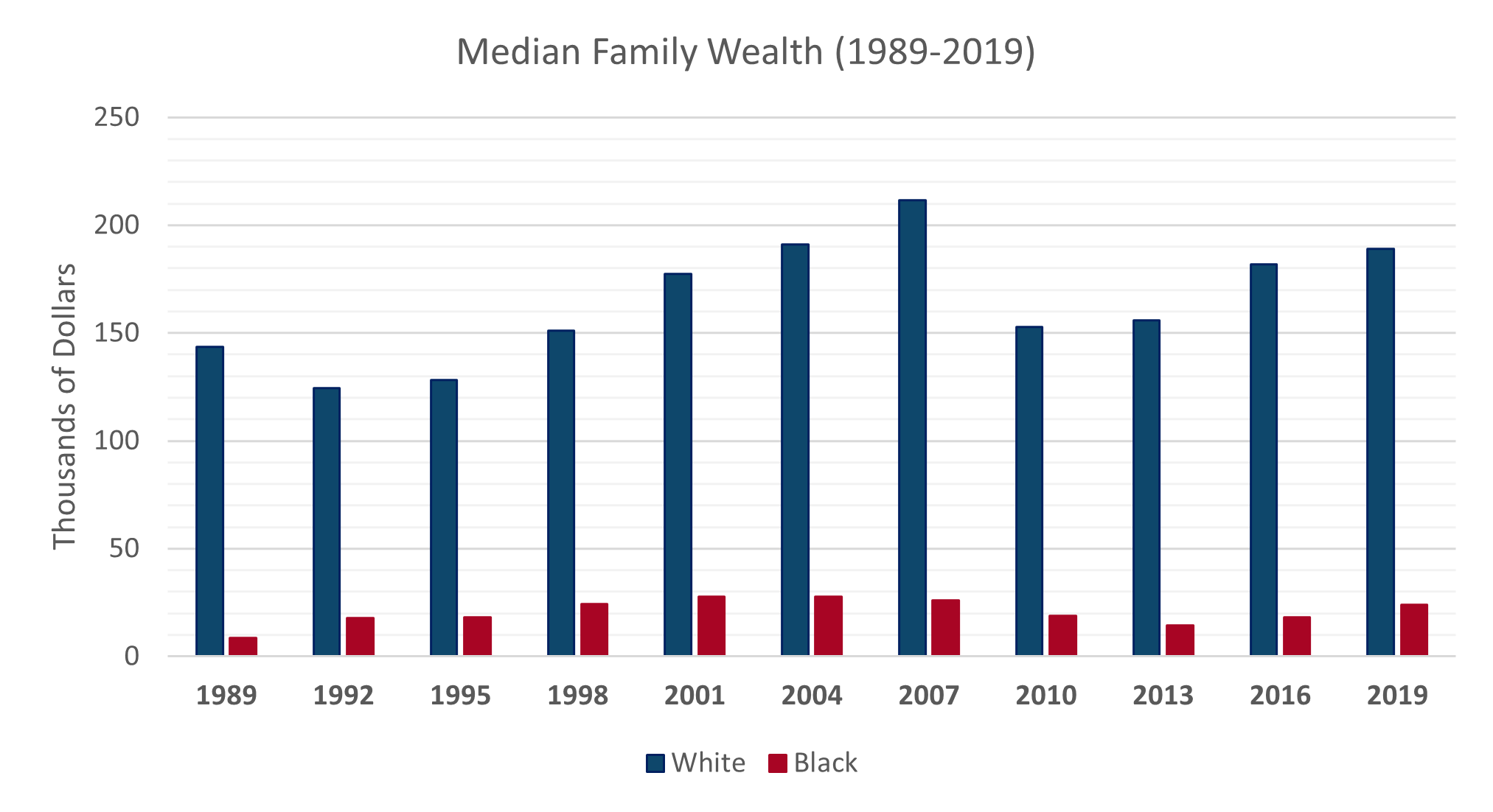

Whether it is discriminatory trade unions, the cycle of low-wage jobs, racist bank lending policies, or redlining in the housing industry, these historical forces still present barriers to Black workers today. For example, Figure 1 shows that the gap in unemployment between Black and white workers has existed for almost half a century. Similarly, as Figure 2 illustrates, the gap in family wealth between Black and white households remains staggering.

Figures 1 and 2: Decades of Disparity in Unemployment and Family Wealth

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate – White [LNS14000003], Black or African American [LNS14000006] retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Source: Federal Reserve Board, Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S. since 1989.

The point is that, in both good economic times and bad, Black workers cannot access the same level of economic security and opportunity as their white peers. Disparity is built into our economy. For that reason alone, recovery talks cannot center pre-pandemic “back to normal” as the goal. Returning to the status quo is not enough, has never been enough, and is a dismissal of Black workers’ generational sacrifices which built this nation’s economy.

With specific policies designed to empower Black workers’ wealth building and economic security, policymakers might avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. Congress should consider priorities including investing in high-quality, high-wage jobs; boosting the federal minimum wage; increasing training and workforce development; cancelling student debt;, and expanding equitable access and pathways to postsecondary education.

Black workers are, and have always been, essential to the economy and to our country. They have also always been at the forefront of labor movements for unionization, fair wages, and safer working conditions—progress that has benefited all workers. It is time to structure an economic recovery that uplifts Black workers who have held up the U.S. economy for so long.