CLASP

The Center for Law and Social Policy

This statement can be attributed to Wendy Chun-Hoon, President and Executive Director of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

Washington, D.C., July 10, 2025 – This week, several federal agencies—including the Department of Agriculture (USDA), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Department of Education (ED), and Department of Labor (DOL)—issued notices regarding reinterpretation of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act that restricts eligibility for some federal programs to “qualified immigrants.” These notices are in response to the Trump Administration’s executive order in February that seeks to deny federal benefits to undocumented immigrants, despite the fact that they are already ineligible for most federal benefits. These latest actions only serve to restrict access to such programs for immigrant families, including U.S. citizen children.

The Trump Administration is undermining more than 30 years of rules between federal and state governments about how grant dollars can be used. These changes will present states, counties, and cities with challenges about how they administer these programs.

Several essential programs are implicated in the HHS rule, including the community health center program, critical mental health and substance use funding for states, community services funds to bolster communities with low incomes, and funding to support foster youth. Head Start is a key program also subject to reinterpretation, potentially compromising eligibility for children in immigrant families, with grave consequences for their early learning and development. For 60 years, Head Start has ensured that children from birth to age 5 and their families have access to educational, health, and family support. Along with the programs noted above, Head Start is specifically designed to support families with low incomes, including immigrant families, by addressing both immediate and comprehensive needs. Additionally, Migrant and Seasonal Head Start helps farmworker families achieve stability and break the cycle of poverty.

Other impacts could include specific ED adult education and postsecondary career and technical education programs, along with certain DOL workforce training programs. While other programs for which immigrants are eligible, including SNAP and WIC, are not currently affected, the uncertainty and confusion around these new notices and guidances could have a wider chilling effect on numerous benefit programs.

This is just the latest assault on immigrants and immigrant families from the Trump Administration, which has used numerous executive orders and the reconciliation bill to cause great harm to immigrant children and families. Although several of these notices only reaffirm existing policy, in some cases–where eligibility is further restricted–agency guidance and possibly public comments will need to be considered before any eligibility is changed.

We urge our partners and allies to submit public comments where possible and join us in opposing efforts to strip away essential supports from immigrant families and undermine our collective well-being. We also urge community members to seek out information from trusted sources on how their eligibility for programs may be affected, including from our partners at the Protecting Immigrant Families Coalition.

This statement can be attributed to Wendy Chun-Hoon, President and Executive Director of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

Washington, D.C., July 3, 2025 – This afternoon, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the budget reconciliation bill, which President Trump is expected to sign on July 4. This bill will cause unprecedented harm across the country, particularly to communities with low incomes, people of color, immigrants, workers, women, and children. CLASP has vociferously opposed the reconciliation bill and is busy working on a strategy for supporting the people at the heart of our mission who will be left to deal with the bill’s catastrophic cuts and spiteful policy changes. Our fight to ensure the dignity, security, and well-being of those who have been most marginalized is far from over, and CLASP is ready to meet the moment.

This statement can be attributed to Isha Weerasinghe, Director of Public Benefits Justice at the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

Washington, D.C., July 1, 2025—The budget reconciliation bill passed today by the Senate on a vote of 51-50, with Vice-President Vance casting the tie-breaking vote, will cause significant harm to millions of children and families, all for the sake of providing more tax breaks for the wealthy. The bill includes substantially more funds to accelerate the devastating immigration enforcement actions that are tearing families apart and undermining the safety and well-being of vulnerable children, including those who are U.S. citizens and asylum seekers.

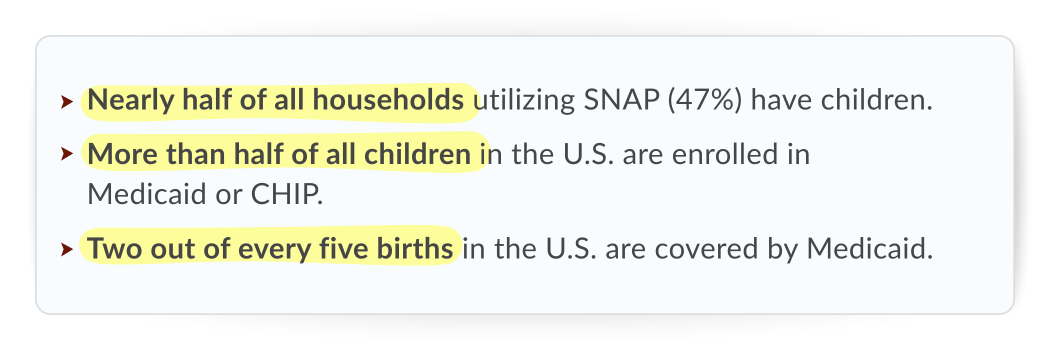

The Senate’s version of the bill contains deeper cuts to Medicaid than the version passed by the House last month, excludes many lawfully present immigrants from eligibility, and expands the House’s work requirement to include some parents, which will cause millions more people to lose health insurance. This means that children and seniors, along with millions of middle-class and working families, people who need long-term care, and those who live in nursing homes will be at risk of losing their health insurance. An estimated 17 million people will lose health insurance, and 8 million people will be at risk for losing food assistance–in the same bill that gives tax breaks to billionaires and corporations.

In addition to these harmful Medicaid cuts, the bill also adds dangerous provisions to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program that will restrict access, tighten eligibility, and shift major costs from the federal government to states, potentially forcing them to end their SNAP programs entirely. This represents a major threat to the health care and food assistance that millions of families depend on for their health, well-being, and stability. The bill also denies immigrants key federal benefits like Medicaid and SNAP that they contribute to, and creates barriers for them to apply for legal or permanent status by raising fees.

The bill will also cut off access to the Child Tax Credit for an estimated 2.6 million U.S. citizen children simply because their only caregiver(s) lack a Social Security number. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy indicates that, under this bill, the wealthiest households in the country will see an average tax cut of about $65,000, while the households with the lowest incomes will only receive an average tax cut of $110. This disparity is particularly stark, given that this bill does nothing to support the needs of families with low incomes who are especially harmed by the lack of affordable child care and increased cost of living.

The Senate bill also affects college affordability and the financial well-being of students by limiting student loans for programs and eliminating repayment options for new borrowers facing economic hardship or unemployment. The bill would also restrict access to Pell Grants for over 4.4 million students, making it harder for students with low incomes to cover costs and finish their programs.

The bill will now go to the House, whose leadership has made it clear that they will push it through as quickly as possible to meet a self-imposed July 4th deadline. Given the disregard for children, workers, immigrants, and families shown in the House’s reconciliation bill, provisions targeting the most vulnerable are likely to remain intact.

Like the House bill, the Senate’s version will harm the health, security, and well-being of communities across the country. CLASP urges House lawmakers to reject this damaging bill and focus on policies that prioritize workers, children, and families over billionaires.

By Sirisha Dinavahi – LA Post

(EXCERPT)

Mental health care is critical for families facing uncertainty. Suma Setty, a senior policy analyst with the Center for Law and Social Policy, noted that even the threat of separation could harm children: “Even just the threat [of deportation or detention of a loved one] is enough to impact a child,” she said.

(EXCERPT)

She isn’t alone. The United States does not require employers to offer paid family and medical leave and paid sick time. Workers who need time off to have a baby, care for a sick relative, or recover from injury or illness depend on the generosity of their company or state (some, including Massachusetts, Washington, and New York, have passed mandatory paid family leave in recent years). And young employees are less likely to get the benefit of employer-paid leave, according to a February 2025 report jointly published by the advocacy group A Better Balance and two non-profit policy organizations, the Center for Law and Social Policy, and the National Collaborative for Transformative Youth Policy.

This statement can be attributed to Wendy Cervantes, director of the immigration and immigrant families team at the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP).

Washington, D.C., June 27, 2025 – Today, the Supreme Court’s opinion in Trump v. CASA curtailed federal judges’ ability to temporarily block Trump’s birthright citizenship executive order (EO) nationwide. This EO would deny birthright citizenship to babies born without at least one parent who is a U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident. The Supreme Court also delays Trump’s EO from going into effect for 30 days.

While today’s opinion does not address the constitutionality of Trump’s birthright citizenship EO, allowing Trump to end birthright citizenship in some parts of the country within 30 days while litigation on the constitutionality of the executive order continues will cause chaos and harm babies, families, and communities.

In the 1898 decision United States v. Wong Kim Ark, the Court confirmed that U.S. citizenship was a birthright of all children born to immigrants in the United States. Now, for the first time in over a century, millions of babies born in this country may be denied automatic birthright citizenship depending on their ZIP code or their ability to prove their parents’ immigration status.

Today’s opinion has profoundly negative consequences for our nation. A large body of research has documented that U.S. citizenship is a key driver of economic growth, educational attainment, and health. Conversely, research also documents that the denial of legal status results in legal, political, economic, and social exclusion to the detriment of stateless children and to the United States.

Even as litigation continues on the constitutionality of the EO itself, families welcoming a new baby in some parts of the country may soon be required to prove their child’s citizenship. This burden will affect not only mixed-status immigrant families but all families in the impacted jurisdiction, undermining the well-being of newborn babies and their parents. Single mothers, families with low incomes, and families of color will be disproportionately impacted by this requirement.

This fight is far from over, and CLASP stands ready to work with partners to ensure that impacted families and service providers are informed about their rights. We urge the Court to uphold the Fourteenth Amendment and rule that Trump’s executive order is unconstitutional. We also call on federal and state policymakers to stand up against the Trump Administration’s reckless attacks on immigrant families and commit to protecting every child born in the United States.

By Suzanne Wikle

In 2017, Republicans were boldly transparent about their attempt to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which narrowly failed. Eight years later lawmakers in both chambers have doubled down on stripping health care from people, first in the House’s 2025 reconciliation bill and now as the Senate considers its version of the bill. The House bill would cause 16 million people to lose their health insurance in the next decade; the Senate version may cause even more damage.

Both bills seek to remove people from health insurance through eligibility changes, increasing red tape and other bureaucratic hurdles to make it too difficult for people to enroll, and allowing people’s monthly premium costs on the Marketplace to skyrocket. Lawmakers are also looking to shift costs to states while reducing their tools for financing Medicaid. If the provisions dismantling the ACA and Medicaid in the reconciliation bill end up on the President’s desk, millions of people will lose their health insurance, costs will soar for millions more, rural hospitals will suffer, and states will face greater budget challenges.

The Senate bill cuts nearly $1 trillion from Medicaid and Marketplace health care, ultimately leaving at least 16 million uninsured and millions more with higher costs to keep their health insurance. Cuts to health care include:

Expanding Eligibility Requirements

Undermining Medicaid expansion as designed in the ACA by creating new eligibility requirements. So-called “work requirements” bury people in paperwork and red tape, making it too difficult to enroll or keep coverage for eligible people. Unlike the House, the Senate bill makes some parents subject to this new eligibility test, which will lead to more people losing their health insurance.

Work reporting requirements do nothing to improve employment, especially living-wage employment that offers health benefits. The truth is that many jobs don’t offer health insurance, and irregular work hours add an extra burden of reporting work hours to the state. The only way to describe “work requirements” is that it is a Medicaid cut. It’s estimated that this provision alone will cause between 5 million and 14 million people to lose their health insurance. Of the small portion of Medicaid enrollees who are not working and are “able-bodied,” nearly 80 percent are older women who have been caregivers and live in families with very low incomes.

Shifting Costs to Consumers

The Senate bill continues the House tactic of shifting costs to people: specifically, by increasing cost-sharing (up to $35/service for some Medicaid enrollees) and changing rules around retroactive coverage. The Medicaid expansion population includes those with incomes between 100 and 138 percent of the poverty level ($15,650 – $21,127 per year for a single person and $32,150 – $44,367 per year for a family of four). Expecting people at these income levels to pay more out of pocket for care means that they may choose not to access care. That could make it more difficult for people to manage chronic conditions or receive care when they are ill.

Currently, Medicaid helps people avoid medical debt by providing retroactive coverage for 90 days. For example, if an uninsured person who qualifies for Medicaid is admitted to a hospital, they can apply for coverage, including coverage of medical bills in the previous 90 days. This is a safeguard against personal medical debt and helps providers ensure they are paid for their services. The Senate bill limits retroactive coverage to one or two months, depending on the person’s eligibility category.

Adding Red Tape

“Work requirements” will add a massive amount of red tape to Medicaid, but the Senate bill also keeps other bureaucratic provisions from the House version, including increasing the frequency of redeterminations from 12 months to six months. This change both increases the state’s workload and costs and is burdensome to enrollees. It will cause significant churn – eligible people will lose coverage and then re-enroll within a few months. Seven hundred thousand people could lose coverage because of this inefficient and wasteful provision. And, again, this is a direct reversal of a key piece of the ACA, which set a 12-month timeline for Medicaid redeterminations (importantly, if a person’s income changes during that 12-month period, they are required to report the changes to the state).

Lastly, the House and Senate bills both repeal a new regulatory rule that was designed to make Medicaid enrollment more efficient and streamlined for the elderly and people with disabilities. Repealing this rule not only keeps unnecessary red tape and hurdles in place, but will also directly cause people to lose coverage.

Shifting Costs to States

Like the House bill, the Senate puts immense financial pressure on states to pay for costly red tape, administrative hurdles, and lost federal dollars. This is one of many examples in the reconciliation bill where Congress claims to “save” money through cutting “waste” but actually makes states bear the cost instead. Significant resources will be needed for states to build IT systems to handle the new work requirements, and more workers will be needed to process those cases and comply with the new six-month redetermination timeline, which doubles the redetermination administrative work for the Medicaid expansion population. The states will have to pay part of these costs.

The changes to Medicaid financing through provider taxes and state-directed payments will cause states to forgo tens of billions of dollars that are currently used to fund their Medicaid programs—either directly or to shore up hospitals and other providers that, without those dollars, might close. It’s unlikely states will be able to entirely backfill those lost dollars; even if they can, that will come at the expense of other state obligations. Again, this is a cost-shift, not a cost-savings.

Restricting State Funds and Programs

The Senate bill also doubles down on the House plan to penalize states based on how states spend state dollars. Some states choose to spend state dollars to provide health insurance to certain undocumented immigrants. The House and Senate bills both call for penalizing these states by forcing them to double the state share for the Medicaid expansion population. That means that the state would have to pay 20 percent instead of 10 percent due to a decrease in federal funding for the Medicaid expansion population. This is only one of many attacks on immigrant coverage.

This provision is yet another repeal of a core facet of the ACA: a 90 percent federal match for the Medicaid expansion population. States will be forced to choose between keeping their 90 percent match or eliminating a state-funded program.

Repealing Tax Credits

Another pillar of the ACA is the Marketplace and providing tax credits to help people afford insurance. During the pandemic, the tax credits were enhanced, making plans more affordable for millions of people. The Senate bill takes the same position as the House – it does nothing to continue affordable coverage for millions of people. The refusal to extend the enhanced tax credits will cause more than 4 million people to lose coverage due to affordability reasons. Plus, the bills go much further to restrict insurance on the Marketplace by shortening the open enrollment period, changing some of the eligibility rules for special enrollment periods, and requiring more paperwork from applicants.

These attacks on Marketplace coverage are an attack on the ACA. Repealing parts that make it affordable and easy to use may not technically be a repeal of the ACA itself, but millions of people will still lose health insurance.

Drastically Changing Health Care

Some of these changes are clear attacks on people’s health insurance, while others are more in the weeds but also incredibly damaging. Collectively, they drastically alter the landscape of Medicaid , which provides health insurance for 20 percent of the country. While neither the House nor the Senate reconciliation bill explicitly repeals the ACA, all of these cuts and requirements are killing the ACA by a thousand cuts—and harming hospitals, providers, and Americans with low incomes the most.

(EXCERPT)

“For far too long, our immigration law has completely disregarded harm to U.S. citizen children, specifically,” said Wendy Cervantes, who advocates for immigrant families and children at the Center for Law and Social Policy. That harm includes the fear that families live in during periods of increased immigration enforcement like this one, as well as the direct impacts of the deportation of a parent.

By Rachel Wilensky and Stephanie Schmit

On March 15, 2025, President Donald Trump signed the Full-Year Continuing Appropriations and Extensions Act, 2025 into law. The law decreased nondefense spending by $13 billion but kept spending levels the same as fiscal year (FY) 2024 for many programs, including the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG). Even though these programs may not be targeted by line-item cuts, with inflation rising, the FY 24 funding levels won’t go as far in FY25. CLASP estimates that approximately 24,000 fewer children will have access to child care through CCDBG in FY25 due to stagnant funding.

>> Read the full fact sheet here

By Juan Carlos Gomez

Families are already struggling with higher costs of living, and the Senate’s budget reconciliation bill will only increase the costs of health care, food, and everyday necessities. The bill’s text affirms that at its core, this is legislation that will drain money from the families with the lowest incomes in order to benefit the wealthy.

Millions Could Lose Health Care, Food Assistance, and Economic Stability

The bill would make the largest cuts to Medicaid and SNAP in history, dismantling the provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace that make it effective in providing affordable health coverage and many free health care services to millions. The proposed language in the Senate makes even deeper cuts to Medicaid and, in total, could cause up to 16 million people to become uninsured. These cuts will cause widespread harm and impact essential workers, like child care providers, who rely on Medicaid due to a lack of access to benefits and low-paying jobs. When Congress tried to repeal the ACA in 2017, they failed because it was deeply unpopular and people understood that weakening the Marketplace would leave millions without affordable health coverage.

Burdensome Work Requirements Are Cuts by Another Name

Burdensome Work Requirements Are Cuts by Another Name

Additionally, the drastic cuts to SNAP could leave over 8 million people with little to no food assistance, harming our economy. Every dollar that goes to SNAP results in up to $1.80 in economic ripple effects that benefit farmers, grocery stores, truck drivers, payment processors, food manufacturers, and others as the funds circulate in the local economy. Less funding for SNAP means families are spending less, impacting more than 250,000 SNAP-authorized retailers nationwide.

The House-passed bill and Senate proposal would create the first mandate for states to implement work requirements in Medicaid programs and make existing SNAP work requirements even more burdensome. Decades of research show that work requirements don’t increase stable employment or economic security. Instead, they lead to large drops in program participation by creating complex, burdensome paperwork that eligible people often can’t navigate. This causes people to lose benefits not because they’re ineligible, but because the system becomes too difficult to access. These policies are especially harmful to people in low-wage jobs, caregivers, and those with health conditions, many of whom already face systemic barriers like discrimination, lack of child care, or unreliable transportation. Work requirements are simply cuts to life-saving programs under a different name.

Millions of Children and Families Will be Barred From Economic Supports

While the Senate bill increases the maximum Child Tax Credit (CTC) to $2,200 per child, it does not make the credit fully available to families with little to no earnings. Under the Senate bill, 17 million children will continue to be left out of receiving the full CTC. Additionally, families that do not have at least one parent with a Social Security number would be barred from accessing the CTC under the Senate bill. This would restrict access to the CTC for 2.6 million citizen children.

The bill would make the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) more difficult to claim for 17 million families with low to moderate incomes by adding a burdensome pre-certification requirement. This would create needless red tape and stress for families with children as they file to claim the EITC. Lawmakers have decreased funding and staffing for the IRS, meaning the agency will have less capacity to provide adequate customer support to parents as they navigate this new policy.

Attacks on Immigrant Communities Will Have Ripple Effects for All Families

Undocumented immigrants are already ineligible for the CTC, Medicaid, Medicare, Affordable Care Act coverage, and SNAP. This legislation bars immigrants who are primarily authorized for humanitarian reasons to be in the United States, like refugees, asylees, and domestic violence survivors, from accessing these programs; in some cases, even green card holders could be blocked. These policies will impact both adults and children: approximately 40 percent of individuals granted refugee status and asylum in FY23 were children.

On top of further limiting immigrant access to essential benefits, this legislation increases funding for mass deportation. Immigrants–including those with authorization–and U.S. citizens alike have been subject to immigration enforcement actions without due process. Over 5 million children have at least one undocumented parent they are at risk of being separated from, and 2.6 million citizen children in the U.S. have only an undocumented parent(s) and are at risk of being left with no one to care for them due to their parent’s detention or deportation. As the Trump Administration continues to strip immigrants of their legal statuses and eligibility for support, the number of children who are harmed by immigration enforcement will grow, the vast majority of whom are U.S. citizens. Fears of immigration enforcement will also cause a chilling effect even among immigrants who qualify for food and health insurance assistance. They will disenroll or not enroll in these lifesaving programs, impacting access for their children and their well-being.

Tax Breaks for the Wealthy Reduce Funding That Supports Children and Families

This bill centers wealthy families by offering tax breaks for the rich while cutting and eliminating essential programs that meet the needs of families. These significant tax breaks mean less revenue to support programs that families rely on and undermine their basic needs. Decisions about investments in programs will come with challenging tradeoffs and will, without a doubt, leave families and children, especially those with the lowest incomes, out to dry. Programs like child care, Head Start, and services for people with disabilities will suffer, and positive progress will be lost.

States and Our Health Care System Will Bear the Burden as Federal Government Withdraws Support

Children and families’ needs for health care and food do not go away just because the federal government chooses not to fund them. Instead, states and local governments–which already have strained budgets–will have to figure out how to implement new, burdensome provisions of the bill and deal with cuts to funding in order to support their residents by shifting costs from other important needs or forcing families off of Medicaid, SNAP, and other essential programs. This bill creates impossible situations for states, forcing them to make decisions about which basic needs they are able to support for the very same families.

As millions of people lose health insurance, the cost of uncompensated care skyrocket, causing tremendous strain on our health care system. This, in turn, could cause hospitals and health care centers to shutter services or close altogether. This will be especially devastating for rural communities where children and families already face barriers to accessible health care, and over 4 in 10 hospitals are already losing money.

The Budget Reconciliation Bill Sets Students, Workers, Children, and Families Up to Fail

Students Will Likely Experience Increased Financial Pressure

Education-related cuts include severe restrictions on federal student aid for students with low incomes at a time when many students already struggle with the increasing cost of pursuing a college degree. Nearly 4.4 million Pell Grant recipients would see their award amounts reduced, and new student loan borrowers would be forced to make larger payments even if they are unemployed or struggling to pay bills. These provisions will drive more borrowers into defaulting on their loans and, as a result, have their CTC and EITC refunds seized. For universities, these restrictions would compound through states being potentially forced to cut education spending to make up for the loss of federal funding for health care and other social services. Institutions would also be forced to no longer offer access to federal student loans, close certain academic programs, or shutter their campuses due to the bill requiring colleges to pay a percentage of unpaid debt.

Workers Face Pay Cuts, Weakened Unions, and Job Insecurity

Workers will see lower wages with rising costs, including for utilities, food, and other necessities in the household. With the continued attacks on unions, all workers face an increase in job security and risk their health and safety at the workplace. And while civil servants have already faced numerous challenges this year due to rounds of layoffs, this bill would cut take-home pay for new civil servants while undermining their workplace rights and limiting federal labor unions’ ability to protect their members.

On top of reducing take-home pay for civil workers, this bill also places a 10 percent tax on labor unions for solely existing in the workplace. Under this bill, it will be increasingly challenging for employees to contest unlawful dismissals or discrimination, and the financial repercussions will be considerably greater for workers aiming to maintain their rights. These changes will affect federal agencies’ ability to retain and recruit workers while placing additional financial burdens on federal workers, their families, and their children.

Young Children and Families Will Not Have Access to Necessary Child Care and Early Education Support

While a child care crisis persists in our country, this bill does nothing to support access to affordable and accessible child care for children and families. While the bill includes a number of tax incentives and credits related to child care, it does not address the true needs of children and families. In fact, even these tax provisions would not benefit families with low incomes, as they are targeted at employers, higher-income jobs, and families with tax liability. It puts no effort into making child care more affordable for the children and families who need it most or supporting the undervalued and underpaid child care workforce.

Resources on budget reconciliation:

- CLASP’s Defending Public Benefits: A Playbook for Policymakers

- Children Thrive Action Network’s Budget Reconciliation Brief

- CLASP’s Infographic: It’s a Cut to Medicaid No Matter What You Call It