CLASP

The Center for Law and Social Policy

This statement can be attributed to Wendy Chun-Hoon, President and Executive Director of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

Washington, D.C., July 3, 2025 – This afternoon, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the budget reconciliation bill, which President Trump is expected to sign on July 4. This bill will cause unprecedented harm across the country, particularly to communities with low incomes, people of color, immigrants, workers, women, and children. CLASP has vociferously opposed the reconciliation bill and is busy working on a strategy for supporting the people at the heart of our mission who will be left to deal with the bill’s catastrophic cuts and spiteful policy changes. Our fight to ensure the dignity, security, and well-being of those who have been most marginalized is far from over, and CLASP is ready to meet the moment.

By Rachel Wilensky and Stephanie Schmit

On March 15, 2025, President Donald Trump signed the Full-Year Continuing Appropriations and Extensions Act, 2025 into law. The law decreased nondefense spending by $13 billion but kept spending levels the same as fiscal year (FY) 2024 for many programs, including the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG). Even though these programs may not be targeted by line-item cuts, with inflation rising, the FY 24 funding levels won’t go as far in FY25. CLASP estimates that approximately 24,000 fewer children will have access to child care through CCDBG in FY25 due to stagnant funding.

>> Read the full fact sheet here

By Juan Carlos Gomez

Families are already struggling with higher costs of living, and the Senate’s budget reconciliation bill will only increase the costs of health care, food, and everyday necessities. The bill’s text affirms that at its core, this is legislation that will drain money from the families with the lowest incomes in order to benefit the wealthy.

Millions Could Lose Health Care, Food Assistance, and Economic Stability

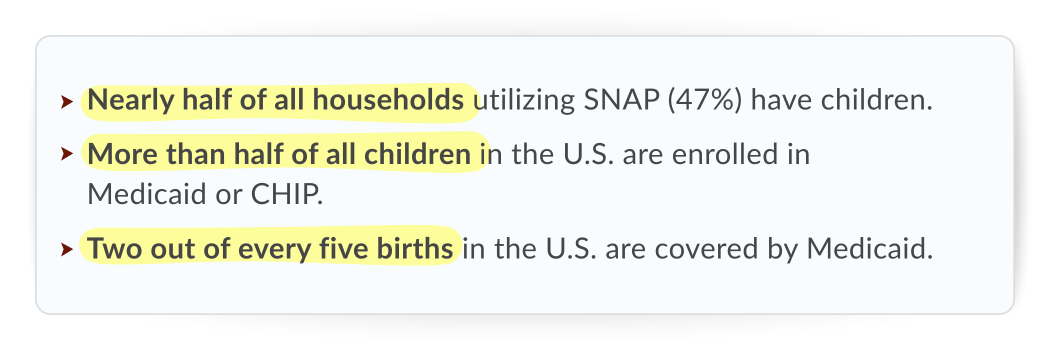

The bill would make the largest cuts to Medicaid and SNAP in history, dismantling the provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace that make it effective in providing affordable health coverage and many free health care services to millions. The proposed language in the Senate makes even deeper cuts to Medicaid and, in total, could cause up to 16 million people to become uninsured. These cuts will cause widespread harm and impact essential workers, like child care providers, who rely on Medicaid due to a lack of access to benefits and low-paying jobs. When Congress tried to repeal the ACA in 2017, they failed because it was deeply unpopular and people understood that weakening the Marketplace would leave millions without affordable health coverage.

Burdensome Work Requirements Are Cuts by Another Name

Burdensome Work Requirements Are Cuts by Another Name

Additionally, the drastic cuts to SNAP could leave over 8 million people with little to no food assistance, harming our economy. Every dollar that goes to SNAP results in up to $1.80 in economic ripple effects that benefit farmers, grocery stores, truck drivers, payment processors, food manufacturers, and others as the funds circulate in the local economy. Less funding for SNAP means families are spending less, impacting more than 250,000 SNAP-authorized retailers nationwide.

The House-passed bill and Senate proposal would create the first mandate for states to implement work requirements in Medicaid programs and make existing SNAP work requirements even more burdensome. Decades of research show that work requirements don’t increase stable employment or economic security. Instead, they lead to large drops in program participation by creating complex, burdensome paperwork that eligible people often can’t navigate. This causes people to lose benefits not because they’re ineligible, but because the system becomes too difficult to access. These policies are especially harmful to people in low-wage jobs, caregivers, and those with health conditions, many of whom already face systemic barriers like discrimination, lack of child care, or unreliable transportation. Work requirements are simply cuts to life-saving programs under a different name.

Millions of Children and Families Will be Barred From Economic Supports

While the Senate bill increases the maximum Child Tax Credit (CTC) to $2,200 per child, it does not make the credit fully available to families with little to no earnings. Under the Senate bill, 17 million children will continue to be left out of receiving the full CTC. Additionally, families that do not have at least one parent with a Social Security number would be barred from accessing the CTC under the Senate bill. This would restrict access to the CTC for 2.6 million citizen children.

The bill would make the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) more difficult to claim for 17 million families with low to moderate incomes by adding a burdensome pre-certification requirement. This would create needless red tape and stress for families with children as they file to claim the EITC. Lawmakers have decreased funding and staffing for the IRS, meaning the agency will have less capacity to provide adequate customer support to parents as they navigate this new policy.

Attacks on Immigrant Communities Will Have Ripple Effects for All Families

Undocumented immigrants are already ineligible for the CTC, Medicaid, Medicare, Affordable Care Act coverage, and SNAP. This legislation bars immigrants who are primarily authorized for humanitarian reasons to be in the United States, like refugees, asylees, and domestic violence survivors, from accessing these programs; in some cases, even green card holders could be blocked. These policies will impact both adults and children: approximately 40 percent of individuals granted refugee status and asylum in FY23 were children.

On top of further limiting immigrant access to essential benefits, this legislation increases funding for mass deportation. Immigrants–including those with authorization–and U.S. citizens alike have been subject to immigration enforcement actions without due process. Over 5 million children have at least one undocumented parent they are at risk of being separated from, and 2.6 million citizen children in the U.S. have only an undocumented parent(s) and are at risk of being left with no one to care for them due to their parent’s detention or deportation. As the Trump Administration continues to strip immigrants of their legal statuses and eligibility for support, the number of children who are harmed by immigration enforcement will grow, the vast majority of whom are U.S. citizens. Fears of immigration enforcement will also cause a chilling effect even among immigrants who qualify for food and health insurance assistance. They will disenroll or not enroll in these lifesaving programs, impacting access for their children and their well-being.

Tax Breaks for the Wealthy Reduce Funding That Supports Children and Families

This bill centers wealthy families by offering tax breaks for the rich while cutting and eliminating essential programs that meet the needs of families. These significant tax breaks mean less revenue to support programs that families rely on and undermine their basic needs. Decisions about investments in programs will come with challenging tradeoffs and will, without a doubt, leave families and children, especially those with the lowest incomes, out to dry. Programs like child care, Head Start, and services for people with disabilities will suffer, and positive progress will be lost.

States and Our Health Care System Will Bear the Burden as Federal Government Withdraws Support

Children and families’ needs for health care and food do not go away just because the federal government chooses not to fund them. Instead, states and local governments–which already have strained budgets–will have to figure out how to implement new, burdensome provisions of the bill and deal with cuts to funding in order to support their residents by shifting costs from other important needs or forcing families off of Medicaid, SNAP, and other essential programs. This bill creates impossible situations for states, forcing them to make decisions about which basic needs they are able to support for the very same families.

As millions of people lose health insurance, the cost of uncompensated care skyrocket, causing tremendous strain on our health care system. This, in turn, could cause hospitals and health care centers to shutter services or close altogether. This will be especially devastating for rural communities where children and families already face barriers to accessible health care, and over 4 in 10 hospitals are already losing money.

The Budget Reconciliation Bill Sets Students, Workers, Children, and Families Up to Fail

Students Will Likely Experience Increased Financial Pressure

Education-related cuts include severe restrictions on federal student aid for students with low incomes at a time when many students already struggle with the increasing cost of pursuing a college degree. Nearly 4.4 million Pell Grant recipients would see their award amounts reduced, and new student loan borrowers would be forced to make larger payments even if they are unemployed or struggling to pay bills. These provisions will drive more borrowers into defaulting on their loans and, as a result, have their CTC and EITC refunds seized. For universities, these restrictions would compound through states being potentially forced to cut education spending to make up for the loss of federal funding for health care and other social services. Institutions would also be forced to no longer offer access to federal student loans, close certain academic programs, or shutter their campuses due to the bill requiring colleges to pay a percentage of unpaid debt.

Workers Face Pay Cuts, Weakened Unions, and Job Insecurity

Workers will see lower wages with rising costs, including for utilities, food, and other necessities in the household. With the continued attacks on unions, all workers face an increase in job security and risk their health and safety at the workplace. And while civil servants have already faced numerous challenges this year due to rounds of layoffs, this bill would cut take-home pay for new civil servants while undermining their workplace rights and limiting federal labor unions’ ability to protect their members.

On top of reducing take-home pay for civil workers, this bill also places a 10 percent tax on labor unions for solely existing in the workplace. Under this bill, it will be increasingly challenging for employees to contest unlawful dismissals or discrimination, and the financial repercussions will be considerably greater for workers aiming to maintain their rights. These changes will affect federal agencies’ ability to retain and recruit workers while placing additional financial burdens on federal workers, their families, and their children.

Young Children and Families Will Not Have Access to Necessary Child Care and Early Education Support

While a child care crisis persists in our country, this bill does nothing to support access to affordable and accessible child care for children and families. While the bill includes a number of tax incentives and credits related to child care, it does not address the true needs of children and families. In fact, even these tax provisions would not benefit families with low incomes, as they are targeted at employers, higher-income jobs, and families with tax liability. It puts no effort into making child care more affordable for the children and families who need it most or supporting the undervalued and underpaid child care workforce.

Resources on budget reconciliation:

- CLASP’s Defending Public Benefits: A Playbook for Policymakers

- Children Thrive Action Network’s Budget Reconciliation Brief

- CLASP’s Infographic: It’s a Cut to Medicaid No Matter What You Call It

By

(EXCERPT)

Alyssa Fortner works as a policy analyst for the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP), a D.C.-based “nonpartisan, anti-poverty nonprofit advancing policy solutions to improve the lives of people with low incomes.” When it comes to child care, the center aims to ensure all children have access to free or affordable child care and early education.

By Rachel Wilensky, Karla Coleman-Castillo, and Wendy Cervantes

In the months since inauguration, the Trump Administration has leveled a staggering number of threats on social programs–from executive orders to funding freezes and staff layoffs–that are already harming child care and early learning programs. These assaults on social infrastructure and aggressive moves to reshape the government are accompanied by increasing attacks on immigrants, many of whom rely on or provide child care and early education (CCEE). With a quarter of children under six coming from immigrant families and almost 20 percent of child care providers and early educators being immigrants, anti-immigrant policies directly affect families with young children and CCEE programs.1 This resource will briefly summarize the available data on immigrant children, families, and child care providers and early educators and examine the impact of the Trump Administration’s anti-immigrant policies on CCEE to date.

By Stephanie Schmit (op-ed)

(EXCERPT)

All of us want our kids to get a fair start in life. And for millions of American families, that start has come from the federal Head Start program.

But unfortunately, President Donald Trump has frozen Head Start funds, laid off many federal Head Start employees, and closed numerous regional Head Start offices across the country. Now a leaked draft of the president’s budget proposes eliminating Head Start altogether.

CLASP submitted this statement for the record in response to the United States Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions “Hearing on Fiscal Year 2026 Department of Health and Human Services Budget.”

CLASP submitted this statement for the record in response to the May 14, 2025 “Budget Hearing-Health and Human Services” of the U.S. House Committee on Appropriations.

By Robin Buller

(Excerpt)

Stephanie Schmidt, the director of childcare and early education at the Center for Law and Social Policy, emphasized that the average cost of infant care in the US is $14,000 per year, with that number ticking up to closer to $25,000 a year in high-cost-of-living areas. “$5,000 gets you almost nowhere when you’re thinking about utilizing it to pay for the expenses of having a young child,” she said.

By Alyssa Fortner

Child care enables parents and caregivers to participate in the workforce, attend school and training programs, and take care of other responsibilities while their children are cared for in safe and stable early education programs. Despite its value, child care has historically been underfunded and inaccessible for the majority of those who need it. Because of this, the funding that states receive through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), the main federal funding source to support families with low incomes in accessing child care, is a vital support for many across the country.

CCDF funding is provided through mandatory funding in the Social Security Act—referred to as the Child Care Entitlement to States—and discretionary funding in the Child Care and Development Block Grant Act (CCDBG) of 1990. States can receive additional child care funding through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant and the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG). Under CCDF, the amount of money each state receives annually is calculated using a formula that considers factors including the number of children receiving free or reduced-price lunches, the state share of children younger than five, and the state’s per capita income.

However, Congress has never adequately funded this program to serve all eligible children. For example, in CLASP’s most recent estimate, only 14 percent—or 1 in 7 children—had access to a CCDF subsidy based on state income eligibility requirements. Limited federal investments in state child care systems mean that far too many families are not getting the critical support that they need.

The historical inequities and systemic racism that plague the child care sector create additional barriers for families of color, including those who are eligible for CCDF. These barriers stem from a long history of policies and practices that often excluded, marginalized, or disproportionately harmed people of color. These impacts continue to be felt in many ways, including in the idea of who deserves care; difficult eligibility requirements; inequitable access to child care subsidies across racial and ethnic groups; and poverty-level wages for early educators of color, particularly Black and Hispanic providers. Working in child care often means low wages, a lack of benefits, and a physical and emotional toll on providers, all of which have created retention and recruitment challenges. This, in turn, has led to persistent shortages in the child care workforce—which further impacts access to care for families and the ability of providers to stay in a role they are passionate about. The impacts of this history have only continued to intensify and became increasingly evident due to the COVID-19 pandemic.