CLASP

The Center for Law and Social Policy

About CLASP

The Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP) is a national, nonpartisan, anti-poverty organization advancing policy solutions that work for people with low incomes and people of color. We advocate for public policies and programs at the federal, state, and local levels that reduce poverty, improve the lives of people with low incomes, and advance racial, gender, and economic justice. Our solutions directly address the barriers that individuals and families face because of race, ethnicity, low income, gender, immigration status, and involvement with the carceral system.

Over more than 50 years we have kept our vision alive through our trusted expertise on policy and strategy, deeply knowledgeable and committed staff, partnerships with directly impacted people and grassroots leaders, and bold, innovative, and inclusive approaches to economic, racial, and gender justice.

At this extraordinarily important moment for the United States, CLASP is actively defending against unprecedented and relentless assaults on the people and policies at the core of our agenda. We are doing so through a mix of congressional advocacy built on our vision, relationships, and deep knowledge; administrative advocacy to fight against the unabating attacks on programs and policies; state-level change, by generating impactful ideas in collaboration with state officials and advocates; and a powerful vision put forward together with on-the-ground leaders.

About the Education, Labor, and Worker Justice Team

CLASP is uniquely positioned within the broader policy advocacy world in our focus at the intersection of jobs, postsecondary education, workforce, adult education, and public benefits – and because we center the experiences of workers and students with low incomes and communities of color in our policy advocacy. Key to our effectiveness is our ability to toggle between federal and state policy and implementation, our core commitment to workers paid the lowest wages—often, women of color—and our trusted relationships with public officials, advocates, and grassroots organizers.

The Education, Labor and Worker Justice (ELWJ) team is laser-focused on ensuring that all jobs are good jobs and all workers—and would-be workers—have ongoing access to education and training opportunities with a focus on those engaged in work paying low wages. The team works to dismantle and reform systemic and institutional failures in the labor market and workforce system that perpetuate widening gender and racial wage and wealth gaps.

The ELWJ team leverages CLASP’s deep expertise on worker benefits, worker protections, worker voice, worker rights advocacy, labor standards enforcement, and racial equity with our crucial role in advancing job creation, workforce development, and postsecondary education policies that uplift people with low incomes who have been historically marginalized by systemic racism, economic exclusion, and immigration-related barriers. The Team Director will lead the ELWJ team.

CLASP has a long-standing commitment to workforce development, foundational skills development, and postsecondary education as key strategies to advance economic mobility, increasing credential attainment, advancing skills, and providing work experience to individuals who face structural barriers to employment. Staff play a leadership role in advancing crucial policies for workers and students of color and those in industries that pay low wages. Working closely with coalition partners, CLASP has been central to shaping the national conversation on addressing the changing nature of low-wage work and addressing systemic barriers to employment and education.

Position Summary

The Director will play a central leadership role in shaping and advancing CLASP’s vision for racial, gender, and economic equity through transformative worker- and student-centered policy solutions. As a key member of the organization’s Leadership team, the Director will collaborate with colleagues to set CLASP’s strategic agenda and cultivate a strong, equity-driven organizational culture. They will mentor staff, set clear performance expectations, develop staff leadership, and foster a collaborative, mission-aligned work environment.

The Director will serve as a leading voice for CLASP’s advocacy on worker benefits, labor protections, job quality, and workforce equity—engaging with funders, policymakers, and national and grassroots partners. They will guide strategy and partnerships that elevate the voices of workers and dismantle systemic labor market barriers for people with low incomes who have been historically marginalized by systemic racism, economic exclusion, and immigration-related barriers. This role includes thought leadership on federal and state policy, cross-team collaboration within CLASP, and strategic fundraising that advances the organization’s mission. The Director will bring a bold vision for inclusive economic justice, leveraging CLASP’s expertise to expand access to good jobs, high-quality postsecondary education, and equitable labor standards enforcement.

Requirements

- Substantial experience at a leadership level as an advocate for postsecondary education, workforce development, good jobs, and/or job quality policies that center people who have been historically marginalized by systemic racism, economic exclusion, and immigration-related barriers, whether in an advocacy organization, as a legislative staffer, through leadership on these issues within government or with an employer, through lived experience, or several of the above.

- Deep policy knowledge and recognized expertise in relation to paid family leave/paid sick days, subsidized jobs, expanding worker power and ownership, worker protections, and related policies strongly preferred.

- Demonstrated ability to effectively recruit, supervise, and lead a diverse team that includes both senior and junior members.

- Skilled at managing and motivating teams, supporting staff growth, and creating a culture of accountability and care.

- Proven ability to identify and develop advocacy strategies.

- Demonstrated experience in effective writing and speaking to a variety of audiences.

- Successful record of initiating and cultivating relationships with partners. Existing relationships with job quality advocates, labor unions and other worker advocates, Hill staff, legal advocates, civil and immigrant rights leaders, and public officials working on job issues are a plus.

- Demonstrated success in fundraising and managing relationships with funders is strongly preferred but not required.

- Demonstrated commitment to improving the lives of people with low incomes, to racial justice, and to CLASP’s vision, mission, and values.

- Demonstrated commitment to addressing racial discrimination and immigration policies that limit access to quality jobs and economic advancement.

- Centers equity with an understanding of barriers faced by people with low incomes impacted by systemic injustice.

- Brings significant leadership and people management experience and thrives in collaborative, team-oriented environments.

- Demonstrates a strong intersectional analysis in their work, with particular awareness of the issues and hurdles impacting people with low incomes who have been historically marginalized by systemic racism, economic exclusion, and immigration-related barriers.

- Skilled in leading partnerships with community-based advocates.

- Collaborative leader who enjoys working closely with other leaders and experts as part of a tight-knit team

- Brings experience in national advocacy and strategic partnerships, broadly, with advocacy experience with Congress.

- Passionate, creative, and effective advocate and leader to build on CLASP’s history and this extraordinary moment in time to get major new policies enacted and implemented.

- Has experience with federal advocacy and strong relationships with key partners across labor, education, and equity movements.

- Effective communicator, fundraiser, and mentor with a track record of supporting staff and securing resources.

- Bachelor’s degree required and a minimum of 10 years of related experience or a master’s degree or other advanced degree and 7 years of related experience.

- At least 5+ years of experience supervising and managing diverse teams, with a demonstrated commitment to inclusive and effective leadership. Proven ability to effectively lead staff at various career stages—including both senior and early-career professionals—in a hybrid work environment.

- Candidates must be based in the Washington, D.C. area or be willing to relocate.

UNION ENVIRONMENT AND POSITION STATUS

CLASP is a unionized organization, but this position is not part of the bargaining unit. Employees are represented by CLASP Workers United (OPEIU, Local 2). CLASP values collaboration, fair labor practices, and constructive engagement with the union. We have just finalized our first Collective Bargaining Agreement, which will be in effect until May 2027.

Compensation:

Salary Range: $150 – 160K

Salary is commensurate with experience. CLASP offers exceptional benefits, including several employer-paid health insurance options, dental insurance, life and long-term disability insurance, long-term care insurance, a 403(b)-retirement program, flexible spending accounts, and generous vacation, paid sick leave, paid family and medical leave, and holiday schedules.

Application Process: Please apply here and include a cover letter with your submission. Applications will be accepted until the position is filled. NO PHONE CALLS, PLEASE.

This statement can be attributed to Isha Weerasinghe, Director of Public Benefits Justice at the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

Washington, D.C., July 1, 2025—The budget reconciliation bill passed today by the Senate on a vote of 51-50, with Vice-President Vance casting the tie-breaking vote, will cause significant harm to millions of children and families, all for the sake of providing more tax breaks for the wealthy. The bill includes substantially more funds to accelerate the devastating immigration enforcement actions that are tearing families apart and undermining the safety and well-being of vulnerable children, including those who are U.S. citizens and asylum seekers.

The Senate’s version of the bill contains deeper cuts to Medicaid than the version passed by the House last month, excludes many lawfully present immigrants from eligibility, and expands the House’s work requirement to include some parents, which will cause millions more people to lose health insurance. This means that children and seniors, along with millions of middle-class and working families, people who need long-term care, and those who live in nursing homes will be at risk of losing their health insurance. An estimated 17 million people will lose health insurance, and 8 million people will be at risk for losing food assistance–in the same bill that gives tax breaks to billionaires and corporations.

In addition to these harmful Medicaid cuts, the bill also adds dangerous provisions to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program that will restrict access, tighten eligibility, and shift major costs from the federal government to states, potentially forcing them to end their SNAP programs entirely. This represents a major threat to the health care and food assistance that millions of families depend on for their health, well-being, and stability. The bill also denies immigrants key federal benefits like Medicaid and SNAP that they contribute to, and creates barriers for them to apply for legal or permanent status by raising fees.

The bill will also cut off access to the Child Tax Credit for an estimated 2.6 million U.S. citizen children simply because their only caregiver(s) lack a Social Security number. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy indicates that, under this bill, the wealthiest households in the country will see an average tax cut of about $65,000, while the households with the lowest incomes will only receive an average tax cut of $110. This disparity is particularly stark, given that this bill does nothing to support the needs of families with low incomes who are especially harmed by the lack of affordable child care and increased cost of living.

The Senate bill also affects college affordability and the financial well-being of students by limiting student loans for programs and eliminating repayment options for new borrowers facing economic hardship or unemployment. The bill would also restrict access to Pell Grants for over 4.4 million students, making it harder for students with low incomes to cover costs and finish their programs.

The bill will now go to the House, whose leadership has made it clear that they will push it through as quickly as possible to meet a self-imposed July 4th deadline. Given the disregard for children, workers, immigrants, and families shown in the House’s reconciliation bill, provisions targeting the most vulnerable are likely to remain intact.

Like the House bill, the Senate’s version will harm the health, security, and well-being of communities across the country. CLASP urges House lawmakers to reject this damaging bill and focus on policies that prioritize workers, children, and families over billionaires.

This statement can be attributed to Wendy Chun-Hoon, executive director and president of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP).

Washington, D.C., May 22, 2025—CLASP is outraged that the U.S. House of Representatives voted today to pass its reconciliation bill. This bill guts health care, restricts access to food, sacrifices our higher education system, and punishes immigrant families, all to provide more tax breaks for wealthy people and corporations. The legislation will now go to the Senate, where further changes are expected to be made.

The reconciliation bill contains numerous policies that will make life even more difficult for millions of children, families, and people living on the margins. Cuts to essential benefit programs will cause disproportionate hardship to communities of color, individuals with disabilities, immigrants, U.S. citizen children with one or more undocumented parents, and college students with low incomes. If signed into law, states across the country will see costs shift to them as the federal government pulls back funding for important programs. This will negatively impact state budgets and force states to push people off Medicaid, SNAP, and end other public services.

Proposed changes to the Child Tax Credit could lead to an estimated 4.5 million children who are U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents no longer benefiting from this credit. Medicaid could see $715 billion in cuts, and an estimated 13.7 million people are at risk of losing health insurance. The new provisions to SNAP would cut nearly $300 billion from the program—marking the largest reduction in its history—meaning 11 million adults and children may receive less food assistance or lose it entirely. A proposed increase of $45 billion in funding for Immigration and Customs Enforcement puts millions of mixed-status immigrant families at risk of being detained and deported as part of the administration’s devastating mass deportation plan. And education-related cuts include severe restrictions on federal student aid for students with low incomes.

These numbers only include people who will be directly harmed by funding cuts. They don’t account for the local economies that will be destabilized by residents having to choose between buying groceries or paying rent, missing work out of fear of immigration raids, or forgoing needed health care because they are no longer covered by Medicaid or afraid to access it even if they are eligible.

Millions of families will lose their health care, access to food, and the Child Tax Credit if this bill is passed into law, and more immigrant children and families will suffer long-term harm. CLASP is opposed to this bill and calls on the Senate to do everything it can to stop this bill from becoming law.

CLASP’s budget reconciliation blog series examines the policies put forward that have particular resonance for children, families, and communities with low incomes. The series can be found here.

CLASP submitted this statement for the record in response to the United States Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions “Hearing on Fiscal Year 2026 Department of Health and Human Services Budget.”

CLASP submitted this statement for the record in response to the May 14, 2025 “Budget Hearing-Health and Human Services” of the U.S. House Committee on Appropriations.

By Christian Collins and Sarah Erdreich

As Congress works to advance the proposed budget reconciliation bill of 2025, CLASP’s series “The 2025 Budget Reconciliation’s Impact on People with Low Incomes” will examine the policies put forward that have particular resonance for the children, families, and communities with low incomes. This is the second blog in the series.

On April 29, the House Education & Workforce committee marked up its portion of the House’s reconciliation bill. The committee voted to advance the legislation, which makes drastic changes to Department of Education programs and initiatives, by a party-line vote of 21-14.

Republicans claim that their legislation will save over $330 billion and make federal education policy more effective. But the details of this plan make it clear that the GOP is sacrificing the future of the country for working people to fund planned tax cuts for the ultra-wealthy. Below, we examine some of the most concerning proposals.

Pell Grants

The committee’s bill would increase funding for the Pell Grants program by $10.5 billion from fiscal year (FY) 2026 to FY2028. However, students would need to take at least 15 credit hours each semester to maintain eligibility, up from the current requirement of at least 12 credit hours per semester. This change would place an unnecessary burden on students who also work, parent, or have other time-consuming responsibilities in addition to pursuing a degree in higher education. As a result, fewer students would be eligible for Pell grants.

Student Loans and Financial Aid

The bill also changes how student loan programs would operate, including ending subsidized loans altogether and causing loan interest to accumulate immediately. In addition, schools would be required to repay a portion of their students’ loans if the students miss payments. Moreover, federal aid would be eliminated if the number of students who miss payments is considered too high. According to the committee’s own data, 98 percent of institutions would have to make these payments, and 75 percent would experience a net loss of federal funding, even factoring in the performance-based incentives and grants included in this bill.

Republicans claim that this will impel schools to put more effort into ensuring their graduates find high-quality jobs. This assertion ignores the fact that schools with higher populations of students having low incomes are more likely to need student loans in the first place, will be disproportionately at risk of losing federal funding, and may be reluctant to even consider accepting students who need aid.

It is also notable that this Republican proposal would change the way that financial aid eligibility is determined. Currently, the amount of federal aid a student receives is based on the cost of attending the school in which they plan to enroll. This new proposal would base the amount on the median cost of attending a similar program nationally. However, no clarity was offered as to how the Department of Education will determine median costs; if they have the workforce to do this, given widespread cuts at the department; and how this would be enforced if the GOP makes good on Donald Trump’s oft-stated vow to dismantle the department altogether.

Loan Forgiveness

Access to all existing income-based plans would be eliminated and replaced with a new “Repayment Assistance Plan,” which could cause borrowers to see a disproportionate spike in their monthly payment whenever they move across the proposal’s arbitrary income thresholds. The bill also proposes collapsing the current standard, graduated, and extended repayment plans into a single “standard” plan with varying repayment lengths based on a borrower’s loan balance. These changes would leave borrowers paying more per month, becoming more likely to land in defaults, and ultimately affect the economic security of millions of borrowers.

The Republican proposal on behalf of the House Education & Workforce Committee is nothing more than a brazen sacrifice of our higher education system to further enrich the wealthy through tax cuts. These measures do not increase educational access for students, make investments into institutions that reflect their role as a public good, or adequately address the growing national concern around student debt. Republicans claim that American higher education needs fiscal reform to maintain future sustainability, but they have only presented policies meant to decimate the system and ensure that only students who are already wealthy can earn degrees.

This statement can be attributed to Cemeré James, interim executive director of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

Washington, D.C., March 21, 2025 – Yesterday, President Trump signed an executive order to follow other recent administrative actions meant to decimate the Department of Education (ED) under the veil of “returning power to states.” His action will disrupt the ability of schools to provide the learning opportunities students need. States already hold the primary responsibility and authority for education, while the ED manages and distributes funds, collects essential data, conducts valuable research, and ensures equity in access to public education. Closing ED will disproportionately harm students of color and children with disabilities, instill fear in immigrant students, and reverse decades of progress in enhancing civil rights protections for all students. This order is also consistent with the administration’s stated goal to undo the progress made through Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility efforts that improve and expand educational opportunities.

Closing the Department of Education (ED) will negatively impact students of all races and economic backgrounds. The department plays a crucial role in supporting and holding schools accountable to ensure children with disabilities receive the services they need to succeed, and that young children have access to high-quality early learning. ED also ensures that students receive an education free from harassment and intimidation, and that they are prepared to attend college, universities, and other post-secondary institutions. The withdrawal of federal funds from institutions that do not align with the political values of the Trump Administration will reduce access to education. Ultimately, these actions will deny young children and students from marginalized communities the same educational opportunities, support services, and protections as their peers.

Contrary to language in the Executive Order that ED has failed children, teachers, and families, the department has long defended students’ civil rights to equal education and ensured educational accessibility for students in every state. Eliminating ED deprives immigrant students, students of color, and students with disabilities of federal oversight to shield them from openly discriminatory state governments. Trump’s actions only serve the purpose of resegregating American education along the lines of race and class.

Executive orders are not laws. Trump’s attempt to enact his education policy agenda outside of existing legal parameters is unconstitutional. The order explicitly acknowledges that ED can’t be closed without the approval of Congress, which is an open admission that the administration is undertaking a shameless effort to violate the separation of powers doctrine upon which our government was founded. CLASP stands ready to fight for the educational rights of all students.

We call on federal and state policymakers to oppose these reckless actions and take steps to slow down and mitigate the harm while also supporting children, families, and educators at risk. In addition, we call on our partners in the education and children’s advocacy spaces to join the effort to push back against these harmful attacks, which are an affront to our collective goals to build a more just and equitable country.

This statement can be attributed to Cemeré James, interim executive director of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

Washington, DC, March 12, 2025—Yesterday, the Trump Administration slashed half of the U.S. Department of Education’s workforce when it laid off approximately 1,300 career staff and 600 probationary employees. A nation’s strength is built on the strength of its public education system, and these actions purposely weaken not only American education but America itself. Mass layoffs also undermine the economy and, if left unchecked, will lead to higher unemployment.

For 46 years, the Department of Education (ED) has helped advance and protect equitable educational opportunities for all students seeking to learn in the United States. The Trump Administration’s “final mission” for the department is to intentionally dismantle it, disregarding both its importance to the nation and the profound unpopularity of shuttering the ED. Allowing Elon Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency to operate the federal government like a private equity firm and unilaterally strip federal agencies of valuable people and resources will be ruinous to students, families, communities, and the economy.

Yesterday’s action is particularly concerning because of the impact on marginalized and vulnerable student populations. Public school systems that rely on federal spending will face increased difficulty in continuing to educate students. With a greatly reduced staff, the ED’s Office of Civil Rights cannot fulfill its obligation to vigilantly enforce federal civil rights laws in schools and among other recipients of ED funding. Researchers will struggle to analyze educational outcomes produced by various federal programs after the elimination of the National Center for Education Studies. Postsecondary students will be unable to begin or continue their educational pathways with the loss of staff capacity to manage financial aid awards. The harm of these cuts to students with disabilities, including the effects on early intervention programs for young children, remains unacknowledged by a Secretary of Education who struggles to remember what IDEA (the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) stands for.

The administration has no intention of resolving these concerns or communicating how it will replace the ED’s essential services and programs. Since Inauguration Day the administration has wielded authority without regard to the democratic process, ignoring the laws or livelihoods they break.

CLASP stands ready to work with and on behalf of students, families, and communities to advance and protect the educational rights of all students. We call on federal and state policymakers to oppose these reckless actions and take steps to slow down and mitigate the harm while also supporting children, families, and educators at risk. In addition, we call on our partners in the education and children’s advocacy space to join the effort to push back against these harmful attacks, which are an affront to our collective goals to build a more just and equitable country.

By Teon Hayes

Budget numbers can feel distant, as if they’re just abstract figures debated by those with privilege in the halls of power. But behind those numbers are people, families, and entire communities that will bear the brunt of decisions made in Washington. The House Budget Resolution proposes sweeping cuts that would affect the amount of groceries people can buy, the education of our children, and access to life-saving health care. The real-world consequences of these reductions will be devastating for millions of Americans.

Food on the Table: The Impact of Agriculture Cuts

For many families, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the difference between having food on the table and going hungry. The proposed $230 billion in cuts to agriculture would likely mean deep reductions to SNAP, hitting families with low incomes, seniors, and children the hardest. These cuts could lead to stricter eligibility requirements, reduced benefits, and rising rates of food insecurity.

For example, a single mother in North Carolina has a full-time job but still struggles to afford groceries for her children. SNAP helps her bridge the gap, ensuring that her family has nutritious meals. If these proposed cuts go through, her family could see their food assistance slashed or eliminated, forcing this mother to make impossible choices between paying rent and feeding her kids.

The Cost of Cutting Education: A Blow to Future Generations

Education is often hailed as the great equalizer but slashing at least $330 billion from education funding threatens to widen disparities and limit opportunities for the next generation of leaders. This isn’t just about numbers; it’s about lost opportunities for millions of students.

Imagine a high school senior in rural Pennsylvania who dreams of becoming a nurse. He plans to attend a public college, relying on federal grants and affordable tuition to make his education possible. However, if these cuts become reality, the public college he wants to attend may be forced to raise tuition, reduce financial aid, and cut essential student support services. A reduction in education funding could mean fewer grants and higher student loan burdens, discouraging this student from pursuing the education he needs to thrive in the workforce. As a result, the cycle of poverty continues.

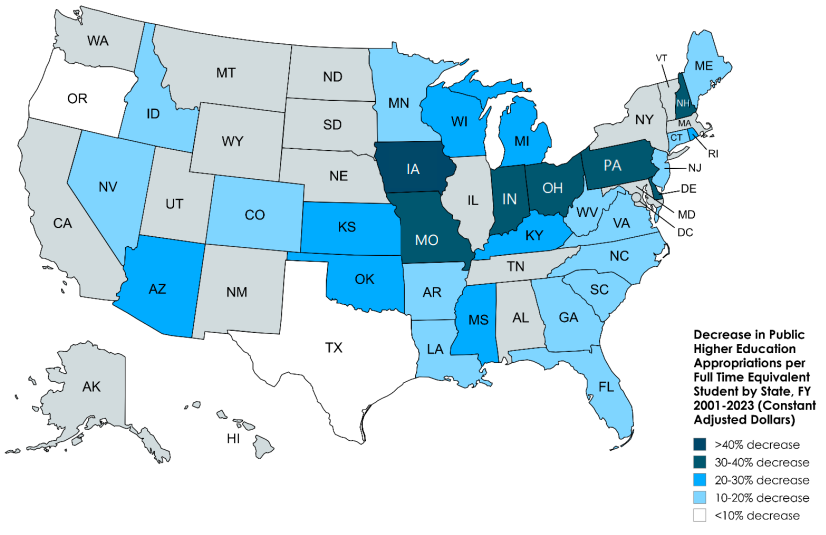

Decrease in Public Higher Education Appropriations per Full-Time Equivalent Student by State, FYI 2001-2023

Source: “Threats to the Department of Education: Private Equity Replacing Public Funding”

The Human Cost of Health Care Cuts

The proposed draft directs the committee that handles Medicaid to cut at least $880 billion, which will likely affect Medicaid most directly. This would have catastrophic consequences for millions of individuals who rely on the program for health care. These cuts could result in reducing coverage for essential services, increasing the number of uninsured Americans, and possibly closing hospitals and nursing homes.

Picture a diabetic patient unable to afford insulin, a child missing critical treatments, or a senior losing access to home health care. Stripping away Medicaid funding doesn’t just take away health care. It endangers lives.

Beyond the Numbers: Why This Matters

These proposed cuts represent real consequences for real people. While policymakers may see this as a fiscal decision, for millions of Americans, it’s a question of survival.

As these discussions unfold, we must ask: who benefits from these cuts, and who suffers? A budget is a moral document that reflects our priorities as a nation. What kind of country do we want to be: one that invests in its people, or one that turns its back on them?

This budget doesn’t just reduce spending; it threatens the stability of millions of families. Single mothers, high school seniors, people with chronic illnesses – they are just some of the real people who will feel the impact of these choices. The United States should be investing in policies that lift people up—ensuring that children have enough to eat, that schools have the resources to educate, and that communities have the support they need to be healthy and thrive.

By Christian Collins

Throughout the 2024 campaign cycle, post-election messaging, and proposed administrative appointments, the incoming Trump Administration has sent a clear message that undermining educational access for marginalized populations will be a priority. These pledges include loosening protections placed by the outgoing Biden Administration against sex and gender identity discrimination at federally funded schools, weakening educational accessibility for immigrant students, and decreasing the racial diversity of the postsecondary system. The most direct threat has been the repeated promise of closing the federal Department of Education (ED) in its entirety, a move that has been attempted multiple times since the department was founded in 1979 but that has failed in every instance.

This brief details the threat that the new administration poses to ED and its impact on post-secondary institutions. It analyzes how there is little political will to close ED, but significant federal education funding cuts are a possibility. Next, the brief outlines how postsecondary institutions are looking to private equity firms to cover potential financial shortfalls and provides policy recommendations for institutions, policymakers, and advocates on pathways to fiscally protect the postsecondary system.