How to End Child Poverty for Good

By Indivar Dutta-Gupta

This is the second in a series of commentaries from CLASP experts that explore dimensions of poverty ahead of the U.S. Census Bureau’s annual release of poverty and income statistics from the previous year. On September 12, we’ll get a snapshot of the economic hardship children, youth and young adults, and families experienced in 2022. Ahead of the release, CLASP experts will offer key insights on the long-term effects of child poverty, promising policy solutions for ending child poverty, links between poverty and mental health, why it’s important to have a more accurate measurement of poverty, and what trends we expect to see in this year’s poverty data.

A family’s income during the prenatal and early years of a child’s life plays a significant role in her health, well-being, and cognitive development, all of which shape her future outcomes. Yet, early childhood is also the time when household incomes can become more volatile, particularly in those headed by single mothers. Evidence abounds on the positive impact that income support programs—especially cash transfers—have on children.

As long ago as the Mother’s Pension program in the early 20th century, we saw that providing cash to families affected by disability resulted in greater longevity and educational attainment as well as higher incomes in adulthood among boys. More recently, a study found that families who received $1,000 more in child tax benefits from 1999 to 2020 had fewer interactions with child welfare and fewer placements in foster care. Yet another study found that a $1,000 increase in income raised children’s math and reading scores. And just in the last few years, we saw that pandemic-era cash transfers reduced the incidence of low birthweight, which can result in adverse health outcomes later in life.

Two years ago, the Congress and the Biden Administration pursued a bold evidence-based experiment by boosting family incomes as part of the pandemic-era relief package, the American Rescue Plan. The expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC) came as close to a universal child allowance as it had in its 24-year history. Unlike previous iterations, the 2021 CTC was fully refundable, meaning it was available even to families with no reported earnings or federal income tax liability. It also increased the annual credit per child to $3,600 for children under age 6 and $3,000 for children ages 6 to 17. Families generally received half the credit through monthly payments from July to December 2021 and the other half in a lump sum after filing their tax returns in early 2022.

A historic reduction in child poverty and material hardship

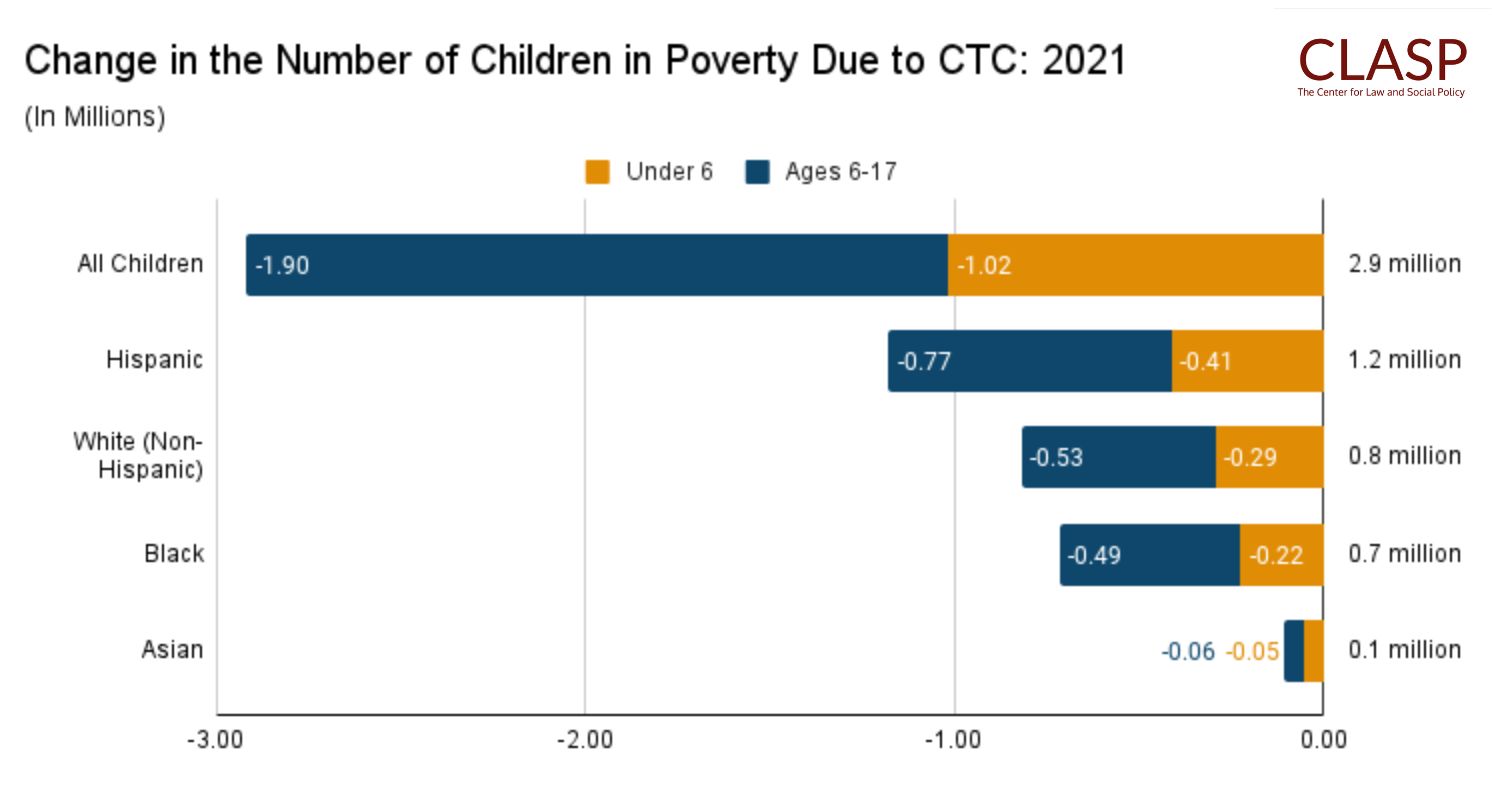

The expanded CTC achieved something monumental: it kept 2.9 million children out of poverty, cutting the child poverty rate by nearly half—from 9.7 percent in 2020 to 5.2 percent in 2021, the largest one-year decline in the child poverty rate on record. Black and Latino/Hispanic children disproportionately benefited in part because previous versions of the CTC did not allow families with low to no earnings to claim the credit. Black and Latino/Hispanic families are more likely to have low incomes due to labor market discrimination, occupational segregation, systemic racism, and other structural barriers. As a result of the expanded CTC, child poverty rates among Black and Latino/Hispanic children shrank by a stunning 8.8 percentage points and 6.3 percentage points, respectively, from 2020 to 2021. Unfortunately, Congress let the expanded version of the CTC expire, and we have reverted to the policy that was passed as part of the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA). This less-effective version offers up to $2,000 annually per child and is not fully refundable, meaning higher-income families are more likely to benefit and working-class families who need the income boost the most aren’t benefiting at all or as much. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that 19 million children under 17 do not receive the full credit, including 45 percent of Black children, 39 percent of Latino children, and 38 percent of American Indian/Alaskan Native children, because of a lack of full refundability. The TCJA also denied the CTC to children who have Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs) instead of Social Security numbers, a blatantly xenophobic and racist departure from the pre-2017 CTC that undermines our own communities and national potential.

Unfortunately, Congress let the expanded version of the CTC expire, and we have reverted to the policy that was passed as part of the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA). This less-effective version offers up to $2,000 annually per child and is not fully refundable, meaning higher-income families are more likely to benefit and working-class families who need the income boost the most aren’t benefiting at all or as much. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that 19 million children under 17 do not receive the full credit, including 45 percent of Black children, 39 percent of Latino children, and 38 percent of American Indian/Alaskan Native children, because of a lack of full refundability. The TCJA also denied the CTC to children who have Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs) instead of Social Security numbers, a blatantly xenophobic and racist departure from the pre-2017 CTC that undermines our own communities and national potential.

How did the expanded CTC help parents?

In an October 2021 survey conducted by CLASP, polling firm Ipsos, and other organizations, parents reported spending the extra income from the CTC on meeting their basic needs and paying grocery bills, rent, or mortgage payments. Nearly 70 percent of respondents said the payments made them feel less financial stress. Black respondents were twice as likely as white respondents to say that the CTC payments helped them work more. Notably, these trends reversed and families faced greater financial strain once the monthly payments ended, according to a July 2022 survey CLASP and partners conducted with parents.

Next steps: Make the CTC fully refundable and inclusive

Although the 2021 expanded CTC didn’t end child poverty for good, it made a significant dent by making it easy for families with the lowest incomes to claim the credit. It was as close to unconditional guaranteed income for families as we had ever come as a nation—and it worked.

I urge Congress to make the CTC fully refundable on a permanent basis. A fully refundable credit is important not only because it reaches families with the lowest incomes, but also because payments are automated and predictable. Monthly payments are important for helping families meet ongoing basic needs, like paying rent, food, and utilities. By one estimate, every dollar spent on a CTC that is more like a universal child allowance generates a return on investment of nearly $10 to society. In addition, for the CTC to reach its full potential to reduce child poverty, it should be accessible to those who are excluded, including children with ITINs and youth either in foster care or otherwise ineligible to be claimed as dependents. We should also ensure families with newborns receive a monthly advance payment.

I also urge the IRS to make the CTC more accessible to families who don’t need to file a tax return or struggle to file one. The IRS should continue experimenting with simplified portals that include free e-file tools, features for reporting new children in the household, and other forms of taxpayer assistance.

But we can’t tell what’s working if we don’t use a poverty measure that reflects the value of public supports, including tax credits, health care, and child care. We’ll explore this topic in our next post.